Doing nothing never did more. 😉 ?Time for the quarterly examination of the composite views of the Federal Open Markets Committee, along with some choice comments on its chief partner-in-crime, the ECB. ? Ready? ?Let’s go!

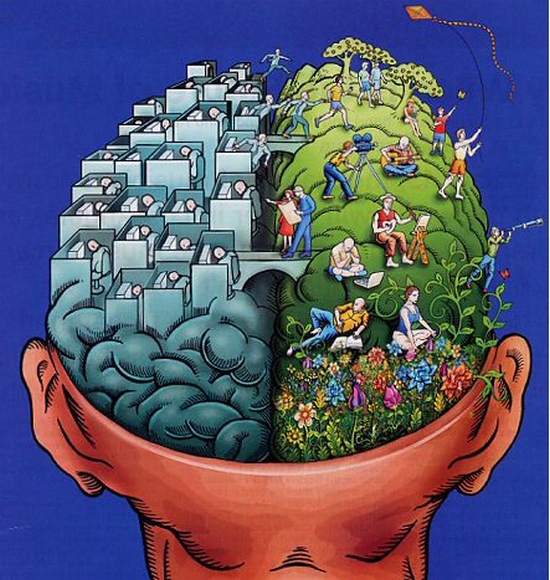

Now, I promised a look inside the?minds of the FOMC, and hypothetically, that what this will be. ?To begin that, you have to recognize the four regularities of FOMC forecasts, as they might think about it:

- We overestimate GDP growth

- We underestimate labor unemployment

- We overestimate PCE inflation

- We overestimate the Fed funds rate

You might ask why they think that way, and if you administered the truth serum, they might say: “We believe the neoclassical view of macroeconomic theory. ?We know?that Fed policy will work, and so we act like we are in control, when we are something in-between being Sorcerer?s apprentices and clinically insane.? We keep doing the same thing and expect a different result.”

Okay, some of that last bit wasn’t fair, at least not fully. ?There *are* some processes where until you do a critical amount of effort, the expected result doesn’t happen. ?But textbook monetary policy isn’t supposed to be that way.

So, take a look at the above GDP predictions graph. ?The “slope of hope” points downhill as the economy does not grow as quickly as they thought it would, given all of their efforts.

The unemployment was similar, except here, they weren’t optimistic enough. ?As it is, they expect unemployment to remain low for a long time, at about the levels that it is now. ?Now, how likely is it for unemployment rates to remain stable for three years? ?Not that likely.

You can almost hear them thinking, “Inflation will come back to 2%. ?After all we’ve been so loose for so long. ?There’s no way it should remain so low when we are creating credit left, right, up, down, forwards and backwards.” ?But then, it doesn’t come — it always stays low. ?Their long run view stays stubbornly at 2%, unlike other views where they let it drift, and that’s because 2% inflation is the religion of the Fed! ?It is the Holy Received Goal, that proper monetary policy will create.

But sometimes they wonder, when it’s dark at night and quiet, “What would it take to create inflation? ?What?”

Finally, they all know that the Fed funds rate will rise. ?It can’t stay low forever, can it?

Behind it all is the nagging worry: “Why doesn’t economic activity pick up?! ?We’re doing everything we can short of doing a helicopter drop of money! ?That has to be enough! ?We don’t want to go to buying investment grade corporates or negative interest rates like that basket-case, the ECB, at least not yet. ?C’mon grow! Grow!”

Note that for each quarter the FOMC has given its projections recently, they have thrown a quarter-percent tightening out the window. ?That’s how overly optimistic they are in setting estimates of future policy.

Leave aside the fact that various risk assets in fixed income land are now flying. ?High-yield isn’t doing badly, but emerging markets debt is taking off — note $EMB which has recently broken its 200-day moving average.

Conclusion

Bad theories beget bad policy tools, which in tern begets bad results. ?The FOMC needs an overhaul of its theories, so that it stops creating speculative bubbles, and learns to be happy with an economy that just muddles along. ?And who knows? ?Give savers a fair rate of return, and maybe the economy will grow faster.

David,

Please forgive the misplacement of this comment. It is Berkshire-related but I’ve tried unsuccessfully to access the comments for those posts.

It seems, from researching insurance accounting on your informative blog and others, that Berkshire is actually NOT using float to buy equities and private stocks. In fact, they are using STATUTORY SURPLUS. Float has always and continues to be be funded with cash and bonds.

http://alephblog.com/2014/03/12/on-the-structure-of-berkshire-hathaway/

This is probably the best of what I wrote on this. It’s actually a hybrid — the equity investments are partially funded by float and by capital. What you might be missing is the amount of capital that must be set aside for equity investments over and about the cost of the investments.

I’ve read the post, but disagree with the idea that equity was funded at all by float. In fact, the amount of float used to buy equities was close to zero. If you look at their holdings going back to 1971, there was never a year in which bonds and cash did not FULLY cover float. Equities were purchased solely with surplus. It was just such a ridiculously amazing group of investments, and the fact that Buffett was betting his entire book value in such stocks (as book value for insurance firms is surplus), that book value went to the stratosphere even without the aid of float-fueled equity purchases.

Hi David

When we look at debt-to-gdp ratios we notice that most Western countries were doing quite well untill the financial crisis. Due to bail-outs the ratios surged (I always like to mention Ireland that had a ratio of 25 % and it went in one year to more than 100 % and still lingers around 95 %). Many other countries, Japan in the frontline, also saw their debt ratio rise due to the more global problem slow growth. Private debt increased too, mainly corporate debt. And looking at $ EMB and $HYG over the past week, the debt-party took off again. Investor’s reaction to the more dovish stand of the Fed, gives me the feeling that every basis point counts nowadays.

I agree it would be more ‘fair’ and economically stimulating to grant the saver some return, However regarding the huge debt situation for many and the attitude of the investors, wouldn’t the consequences be devastating by triggering a debt crisis? My guess is that the debt issue will kick in faster than we can stimulate growth.

I think we are going to get a debt crisis at the end of this anyway. Part of my view is that we can’t keep running a bubbly monetary policy forever… it will eventually blow up. How big do you want it to be when it blows up? The Federal reserve is saying “Very, very big. We want to go down in the history books as the ones who invalidated abnormal monetary policy, and macroeconomic intervention generally.”