Unstable Value Funds (VII)

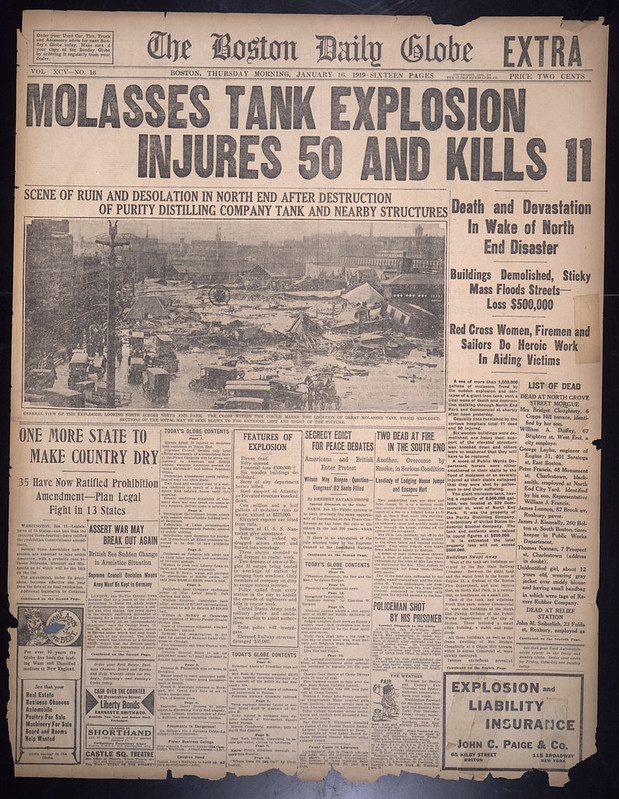

Picture Credit: Boston Public Library || When total systemic leverage is so high, you can’t tell what might go wrong

Because of the fall in interest rates since the last post, the risks have declined with Stable Value Funds. That said, the FOMC still sounds hawkish, even though the yield curve is inverted. The FOMC needs fewer macroeconomists, and more economic historians. They are deluded by the bad models of the last fifty-five years, which lack any credibility outside of the sterility of academia.

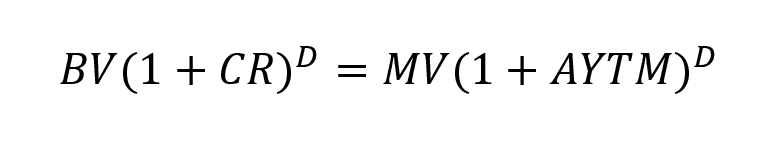

Here are the two equations that I left out of the last piece. How to calculate the premium/discount of a stable value fund:

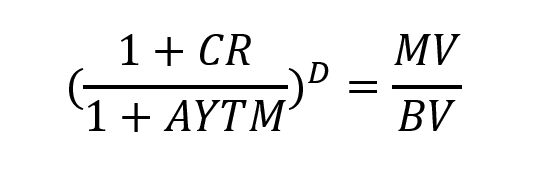

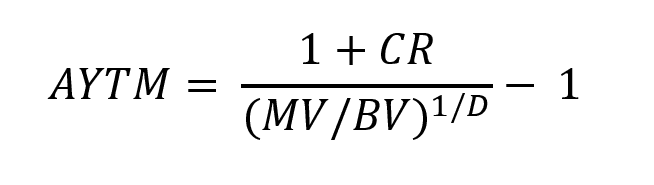

How to calculate the annualized yield to maturity:

Here are the definitions:

BV: Book value — the accrued value of the stable value fund assets so far.

MV: Market Value — the market value of the assets now, if we are able to liquidate the assets at current prices.

AYTM: Annualized Yield to Maturity — the annualized rate that the assets are yielding at current market prices. Note that if you have the SEC Yield, that is the Semiannual yield to maturity, sometimes called the bond-equivalent yield [YTM]. To convert YTM to AYTM:((1 + YTM/2)^2) -1 = AYTM.

D: Effective Duration — The first derivative of Market Value with respect to AYTM. For those that have not taken Calculus, or have forgotten what that means, it measures the sensitivity of market value to small moves in the AYTM. A bigger D means the market value changes more than a smaller D. (And always remember, as interest rates rise, the value of all ordinary bonds goes down.

It is called effective duration, because on a present value basis it measures the weighted average time at which you can expect to receive the cash flows, typically measured in years.

CR: Credited Rate — Though all of these values are artificial in some sense (channeling my best Matt Levine), this one is the most artificial. It means this: in the past the book value accrued to its current value. Now, over the length of time expressed by the Effective Duration, what should the current credited rate be in order for the book and market value to converge? The credited rate is a figure that is like a “heat-seeking” missile, always adjusting (monthly or quarterly) to new conditions as the book value chases the market value. When book value is above market value, the credited rate slows down relative to the AYTM. When the book value is below the market value, the credited rate speeds up relative to the AYTM.

Unstable Value Funds (VI)

As my reader who prompted the last post wrote:

I’m trying to get my head around the implications of the lower MV/BV ratios, but I’m not sure I completely understand the how the crediting rate mechanism works with respect to inflows and outflows.

As I understand it, when MV/BV is less than one, inflows are going bring it closer to par and outflows will further decrease it (assuming outflows are at BV), yes? There are not separate calculations for different plans or different participants, correct? I feel like this may not be a big concern under more typical market conditions, but with MV/BV so low people’s crediting rates are going into look a lot less competitive relative to the returns available with other conservative options and there is more incentive to do as you describe and take the short-term risk in a non-competing fund. Plans leaving is one thing, but a significant participant lead outflow would be much harder to manage, wouldn’t it?

Also, you mention duration longer than 5 being potentially worrisome, but isn’t possible that funds may extend duration early next year as a way of simultaneously goosing the crediting rate and positioning to recoup some losses in anticipation of a Fed pivot? But if rates go higher than expected….

Private email to me

She is a bright lady; she understands it perfectly. Given the recent lower inflation estimates, maybe everything works out easily. But will the FOMC understand that and stop raising the Fed funds rate? Given their desire to appear bold, I think the answer is no. And so I repeat my advice from my last post:

It is not a bad idea now for most participants to move your stable value assets to a balanced fund for 30 days, then move that to a short-to-intermediate term bond fund. You will escape the low-yielding and possibly defaulting stable value fund. You will also earn more from the bond fund.

Remember, there is no FDIC for stable value funds. Watch out for your own best interests while most people don’t notice.