Separate Processes

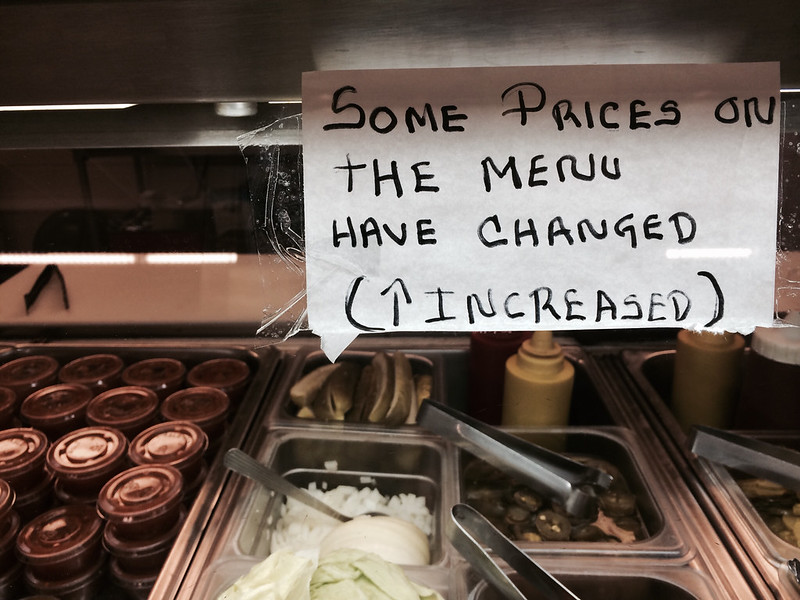

Photo Credit: atramos || Inflation isn’t the most organized phenomenon, and investors often all want to be on the same side of the boat…

I have a very irregular series called, “Problems with Constant Compound Interest.” Part of the idea of that series is that it is difficult to assure growth in capital in any sort of constant way. The simple models of the CFPs, and even actuaries that assume constant or near constant growth are ultimately doomed to fail if they try to exceed growth in nominal GDP by more than 2%/year.

Because of the oddities in the current market environment, current interest rates and inflation have decoupled. They are separate processes. We all want to build value in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, but how do you do that in an environment where price to free cash flow multiples are sky high, nominal interest rates are low, and the prices of most commodities are high as well (leaving aside gold as an oddity). Mindless stock bulls talk of TINA [There Is No Alternative (to buying stocks)], as if there is no limit to how high stock prices can go when interest rates are low. I want to tell you about TIN. There Is Nothing (worth buying). This is the nature of financial repression.

If you invest in short bonds, you get gouged by current inflation. If you buy long bonds, you run the risk that the Fed might start monetizing Treasury debt directly, and inflation really runs. With stocks you run the risk of any hiccup in the global economy (when is the omega variant coming so that we can move on to Hebrew letters?) can derail the market, particularly if it leads to higher interest rates.

The Fed has gotten its wish and is forcing an asset bubble on the US to aid growth, however fitfully. All of the relationships of the present to the future are out of whack, because interest rates are too low. But if intermediate interest rates rose to the level of nominal GDP growth, we would see deficits grow even more rapidly as the US government would refinance at higher rates. The Fed is stuck in a doom loop of its own design ever since Alan Greenspan got the great idea to cut short recessions too soon. That has led us into a liquidity trap designed by the Fed.

As I said to one of my clients this week (a bright man), “If you are not bewildered, you are not thinking.” About the only idea I can think of for investing at present is the intersection of high quality and low-ish valuations. As it says in Ecclesiastes 11:2 “Give a serving to seven, and also to eight, For you do not know what evil will be on the earth.” Diversify among safe-ish investments, with a few cyclicals that will do well if things run hot, and stable businesses, if things do not.

That’s all.