Too Much Debt

Photo Credit: Steve Rotman || As Simon and Garfunkel sang, “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls…”

Debt-based economies are unstable. Economies with a lot of short-term debt are more unstable. The Fed is like Johnny One-Note, or Fat Freddie with a hammer. They only know one tool, and it will solve all problems.

Are there problems from too much debt? More debt will solve the problem. Shift debts from the private to the public sector. Don’t let the private market solve this on its own.

Though the bed debt is not in the same place as the last crisis, we are once again trying to play favorites through the Federal Reserve and rescue entities that took too much risk.

My view is let them fail. The whole system is not at risk, and the COVID-19 crisis will pass in two weeks. The great risk is not from the disease, but from the ham-handed response from policymakers who are short-sighted, and highly risk averse to the point of not wanting to cross the street for fear of dying.

Have we become like the Chinese, who bail out their banks and non-banks regularly? Who can’t bear to see any significant institution fail?

(Yes, I know they are getting more willing to see entities fail in China, but why are we getting less that way in the US? Let market discipline teach companies to not have so much debt.)

Here are three things to consider:

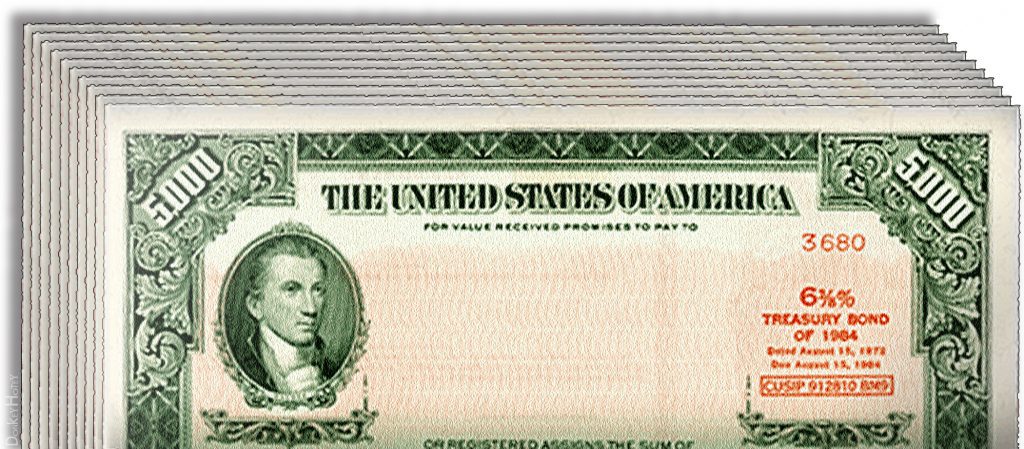

- Bond ETFs Flash Warning Signs of Growing Mismatch — The Fed now think its purview extends to managing the discounts of bond ETFs? Let the system work, and let profit seeking institutions and individuals benefit from artificially high yields. Let insurance companies do what I did: purchase a cheap package of bonds in an ETF, and convert it into the constituent bonds, and sell those that you don’t want for a profit. (Losses from ETFs premiums and discounts are normal, and it is why the dollar weighted returns are lower than the time-weighted returns.)

- The same applies to repo markets. As I have said before, the accounting rules need to be changed. Repo transactions should not be treated as a short-term asset, but as a long asset with a short-term liability, because that is what it is. With Residential Mortgage-Backed SecurIties in trouble, the market should be allowed to fail, to teach those who take too much risk to not do that. This failure will not cascade.

- The same applies to the crony of Donald Trump — Tom Barrack. He pleads his own interest, seeking for the Fed or the Treasury to bail him out, and those who are like him. Let him fail, and those who are like him.

Market participants need to know that they are responsible for their own actions, particularly in a small and short-lived crisis as this one. COVID-19 as a systemic crisis will be gone within weeks.

My statement to all of those listening is “When will we set up a more rational system that discourages debt?” We could made dividends tax-exempt, and deny interest deductions for non-financial corporations, including financial subsidiaries of non-financial corporations. Of course we would grandfather prior obligations.

Are we going to wait for the grand crisis, where the Fed will continue to extend credit amid roaring inflation, or where extend no credit amid a tanking economy? This is what eventually faces us — there is no free lunch. The Fed can’t create prosperity via loose monetary policy, and Congress cannot create prosperity via loose fiscal policy.

The bills eventually come due. The USA might get the bill last after the failure of China, Japan, and the EU, but it will eventually get the bill.

As such, consider what you will do as governments can’t deal with the economic and political costs of financing the losses of the financial system.