GameStop: The Voting Machine Versus The Weighing Machine

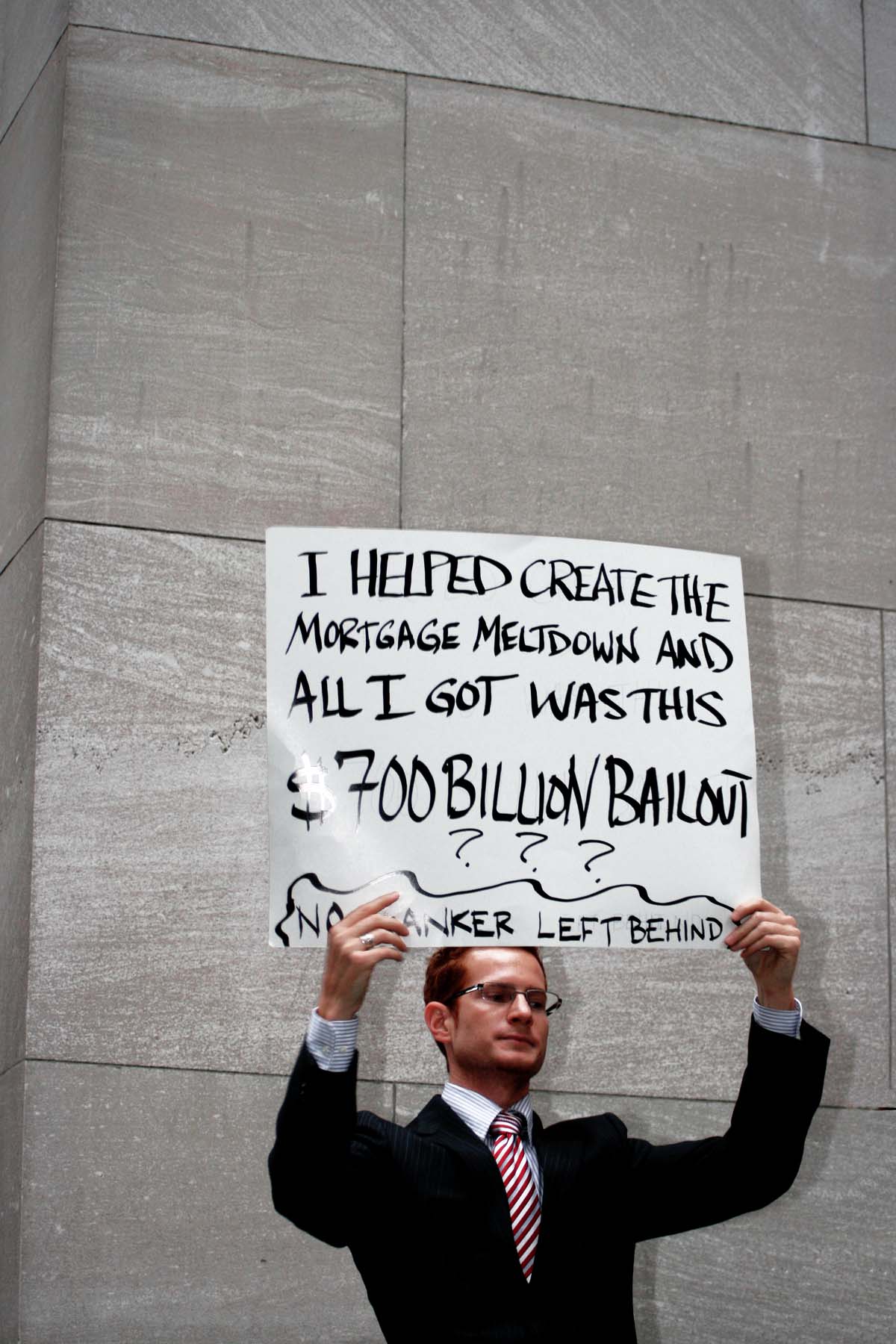

Photo Credits: Seattle Municipal Archives, Luis Anzo, piepjemiffy & Pine Tools || Truth is stranger than fiction, particularly with the behavior of crowds in markets

Before I start writing this evening, I want to say that what I write here is correct in its major findings, but it is quite possible that I got some details wrong. This is complex, and there are a lot of issues involved.

I’ve had four friends ask me about GameStop [GME] over the last few days. Thus I am writing an explanation as to why things are so nuts here.

As a prelude, I want to tell everyone that I have no positions at present in GME, and have no intentions of taking a position in it ever. Mid-decade, I owned GME and lost a little bit on it. I came to the correct conclusion that their business model no longer worked before most of the market gave up on it. If anything, the business model is worse now than when I sold. I think the true value of GME is about $5/share, unless management does something clever with its overvalued stock. Fortunately, I have written a really neat article called How do you Manage a Company when the Stock is Considerably Overvalued? I’ll talk about this more toward the end of this piece.

One more note: I never short because it is very hard to control risk when shorting. When you are short, or levered long, you no longer control your trade in full, and an adverse price move could force you to buy or sell when you don’t want to.

I can imagine working at the hedge fund, and my boss says to me, “What should I do about GME?” My initial answer would be “Nothing, it’s too volatile.” If pressed, I would say, “Gun to the head, it is a short, if you can source the shares, and live with the possibility of being forced by the margin desk to put more capital.”

Now you know my opinion. Let me explain the technicals and the fundamentals here.

The Voting Machine

Ben Graham used to say that the stock market was a voting machine in the short-run, and a weighing machine in the long-run. In a mania, you can get a lot of people chasing the shares of a speculative company like GME, and in the short run, the aggressiveness of the buyers lifting the ask and buying call options can drive the stock higher.

With GME, there is another complicating factor — there are more shares shorted than there are shares issued. This means that some brokerages have been allowing “naked shorting,” i.e., allowing traders to sell short without borrowing shares. This is illegal, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see the SEC pursue a case against some brokers as a result.

When there are a lot of short sellers in a given stock, if buyers can get the price to rise, it can create a temporarily self-reinforcing cycle as shorts are forced by their brokers to put up more capital, or buy in their short position. This is called a “short squeeze.” I’m pretty certain that has been happening with GME.

Now, beyond that there are several other factors:

- Longs that are locked because of large positions

- Use of call options to magnify gains (and maybe losses)

- Co-ordinated buying by small traders.

- Possible use of total return swaps

- Moving shares to the cash account

I’ll handle these in the above order. There are three entities that own more than 10% of GME. Blackrock, Fidelity, and RC Ventures (the investment vehicle of Ryan Cohen, CEO of Chewy.com). Once you own more than 10% of a company, you can’t sell shares until six months have passed since your last purchase. If you purchase more, you must notify the market within two days. If you finally get to the point where you can sell, you can’t buy again for six months, and if you sell you must notify the market within two days.

RC Ventures, which now has three board seats on the GME board, can’t sell GME shares until mid-June, as they bought their last shares in December. I have no idea when Blackrock and Fidelity last bought GME shares but it six months have passed, I would be bombing the market with shares. Since I haven’t seen a filing by either one, I assume they can’t do it for now.

With call options, when a call is sold, the writer of the option must either:

- Bear the risk in full

- Buy other call options to hedge, and/or

- Buy GME stock to hedge, with the risk that you will have to buy more if the stock goes higher, or sell if the stock goes lower.

Buying call options is a leveraged strategy — you can win or lose a lot — usually it is lose. On net, the market is not affected much — for every buyer there is a seller, and derivative positions like calls net to zero. The only time when that is not true is when prices move so fast that margin desks can’t keep up. At that point, brokers take rare losses.

Co-ordinated trading by small traders, perhaps influenced by wallstreetbets at Reddit is something new-ish, though it is reminiscent of the bull pools that existed in the early 20th century. The main difference is that it is a lot of little guys versus a few big guys. Regulations today call a few big guys trying to manipulate the price of a stock “market manipulation,” which is illegal. That does not apply to little guys talking to each other, most likely.

But there is a greater problem here. Even if you are participating with wallstreetbets, how do you know when others will sell to lock in profits.? It’s not as if anyone is looking at the likely flow of future dividends. The dividend has been suspended. Eventually the willingness of the “bull pools” to extend more liquidity will run out. Then there will be a run for the exits — this is a confidence game. Don’t be a bagholder.

With respect to total return swaps, it is the same issue as call or put options. Someone has to take the other side of the trade, and either bear the risk or hedge the risk. There usually should be no net effect.

Finally, there is moving GME shares to the cash account, which means those shares can’t be borrowed in order to short them. There are two points here:

- There is already illegal naked shorting going on here, so moving shares to the cash account may not do much.

- If you are a monomaniac, and are pursuing only GME, you might decide to lever your position via margin. At that point it is not possible to move shares to the cash account.

That takes care of the technicals, now on to the fundamentals.

The Weighing Machine

The fundamentals of GME are lousy. How many of you know their debt ratings? I see one guy in the back raising his hand at half mast. Well, let me tell you that GME has two bonds outstanding:

- $216+ million of a secured first-lien note rated B2/B- maturing in 2023 with a 10% coupon trading in the mid-$103 area for a mid-6% yield-to-worst, which GME can’t likely call.

- $73+ million of an 6.75% unsecured note rated Caa1/CCC+ maturing in less than two months with a mid-5% yield.

Both of these notes are trading above par, but they still trade as junk. If it were not from the interest of RC Ventures they would trade a lot lower. They did trade much lower before RC Ventures bought their stake — yields for the unsecured debt exceeded 40% annualized.

This is a troubled company that would be teetering on the brink of bankruptcy were it not for the efforts of RC Ventures. As such, I would say that the value of GME is at most the price that RC Ventures is willing to pay for it, and that amount is uncertain. (Did I mention that they are losing money regularly?)

And to the bulls I would add, don’t discount the possibility of a trading suspension where you can’t get out of your positions. I can tell you that if that happens the price of GME will be a LOT lower when trading resumes.

What is not “Advice”

Here is my non-advice for everyone.

For those that own GME, sell now. I said NOW, you waited ten seconds.

For those that are short GME, hold your short to the degree that you can.

To the management of GME, do a PIPE, sell a convertible bond or preferred stock. Buy another company in a stock swap. Do anything you can to monetize the idiocy of the bull pool at wallstreetbets. They are offering you a free lunch. Hey, and as an added incentive, RC Ventures can’t sell right now, but you can. Every bit of monetization that you do will benefit RC Ventures to a degree, and dilute them as well (a plus!).

Take the dopes at wallstreetbets to the cleaners, and show them the power of the primary market as you dilute them. Oh, and while you have the opportunity, pay off your bonds, or at least set the money aside in escrow to redeem them at the call date. That is the rescue strategy for GME: sell stock to the losers who have foolishly bid the price up, and use it to rebuild you business. Even RC Ventures may thank you.

Full disclosure: no positions in GME