I get fascinated at how we never learn. Well, “never” is a little too strong because the following article from Bloomberg, Meet the 80-Year-Old Whiz Kid Reinventing the Corporate Bond had its share of skeptics, each of which had it right.

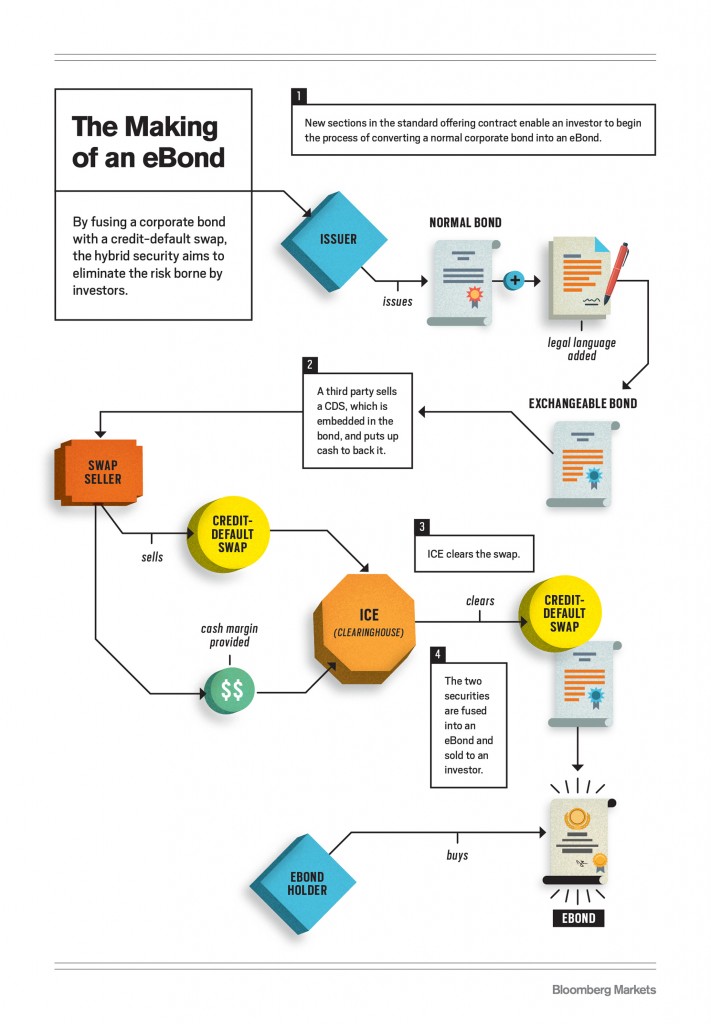

The basic idea is this: issue a corporate bond and then package it with a credit default swap [CDS] for the same?corporate bond, with the swap cleared through a clearinghouse, which should have a AAA claims-paying ability. ?Voila! You have created a AAA corporate bond.

Or have you? ?Remember that bond X?guaranteed by?Y has many similarities to bond Y guaranteed by X, because both have to fail for there to be a default. ?I used to help manage portfolios that had many different types of AAA bonds in them. ?Some were natively AAA as governments, quasi-governments (really, Government Sponsored Enterprises) like Fannie and Freddie, or corporations. ?Some were created by insurance guarantees from MBIA, Ambac, FGIC, or FSA. ?Others were created via?subordination, where the AAA portion took the losses only if they were greater than a highly stressed level. ?Lesser lenders absorbed lesser losses in exchange for the ability to get a much greater yield if there was no default.

There is a lot of demand for AAA bonds if they have a high enough yield spread over Treasuries. ?The amount of spread varies based on the structure, but greater complexity and greater credit risk tend to raise the spread needed. ?Here are some simple examples: At one time, you could buy GE parent corporate bonds rated AAA, or GE Capital corporate bonds with an identical rating, but no guarantee from GE parent. ?The GE Capital bonds always traded with more yield, even though the rating was identical. ?AIG had a AAA credit rating, but its bonds frequently traded cheap to other AAA bonds because of the opacity of the financials of the firm (and among some bond managers, a growing sense that AIG had too much debt).

So?how would one get a decent yield spread?under this setup? ?The CDS will have to require less spread to insure than the spread over Treasuries priced into the corporate bond.

How will that happen? Where does the willingness to accept the credit risk at a lower spread come from? ?Note that the article doesn’t answer that question. ?I will take a stab at an?answer. ?You could get a number of hedge funds trying to make money off of leveraging CDS for income, the excess demand?forcing the CDS spread below that implied by the corporate bond. ?Or, you could get a bid from synthetic Collateralized Debt Obligations [CDOs] demanding a lot of CDS for income. ?I can’t think of too many other ways this could happen.

In either case, the CDS clearinghouse is dealing with weak counterparties in an event of default. ?Portfolio margining should be capable of dealing with small negative scenarios like isolated defaults. ?Where problems arise is when a lot of default and near defaults happen at once. ?The article tells us what happens then:

ICE requires sellers of swaps to backstop their contracts with various margin accounts. If the seller fails to pay off, then ICE can tap a ?waterfall? of margin funds to make the investor whole. In the event of a market crash, it can call on clearing members such as Citigroup and Goldman Sachs to pool their resources and fulfill swap contracts.

There?s still a danger that the banks themselves may be unable to muster cash in a crisis. But this shared responsibility marks a sea change from the bad old days when investors gambled their counterparties would make good on their contracts.

That shared responsibility is cold comfort. ?Investment banks tend to be thinly capitalized, and even more so past the peak of a credit boom, when events like this happen. ?Hello again, too big to fail. ?Clearinghouses are not magic — they can fail also, and when they do, the negative effects will be huge.

Two more quotes from the article by those that “get it,” to reinforce my points:

The bond is a simple instrument with a debtor and creditor that?s proven its utility for centuries. The eBond inserts a third party into the transaction — the seller of the swap embedded in the security who now bears its credit risk.

Such machinations may be designed with good intentions, but they just further convolute the marketplace, says Turbeville, a former investment banker at Goldman Sachs.

?Why are we doing this? Is our society better off as a result of this innovation?? he asks. ?You can?t destroy risk; you just move it around. I would argue that we have to reduce complexity and face the fact that it?s actually good for institutions to experience risks.?

and

?The way we make money for our clients is by assessing risk and generating risk-adjusted returns, and if you have a security that hedges that risk premium away, then why is it compelling? I would just buy Treasuries,? says Bonnie Baha, the head of global developed credit at DoubleLine Capital, a Los Angeles firm that manages about $56 billion in fixed-income assets. ?This product sounds like a great idea in theory, but in practice it may be a solution in search of a problem.?

And, of course, fusing a security as straightforward as a bond with the notorious credit-default swap does ring a lot of alarms, says Phil Angelides, former chairman of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, a blue-ribbon panel appointed by President Barack Obama in 2009 to conduct a postmortem on the causes of the subprime mortgage disaster. In September 2008, American International Group Inc. didn?t have the money to back the swaps it had sold guaranteeing billions of dollars? worth of mortgage-backed securities. To prevent AIG?s failure from cascading through the global financial system, the U.S. Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury Department executed a $182 billion bailout of the insurer.

?When you look at this corporate eBond, it?s strikingly similar to what was done with mortgages,? says Angelides, a Democrat who was California state treasurer from 1999 to 2007. ?Credit-default swaps were embedded in mortgage-backed securities with the idea that they?d be made safe. But the risk wasn?t insured; it was just shifted somewhere else.?

The article rambles at times, touching on unrelated issues like index funds,?capital structure arbitrage, and alternative liquidity structures for bonds. ?On its main point the article leave behind more questions than answers, and the two big ones are:

- Should a sufficient number of these bonds get issued, what will happen in a very large credit crisis?

- How will these bonds get issued? ?When spreads are tight, no one will want to do these because of the cost of complexity. ?When spreads are wide,?who will have the capital to offer protection on CDS in exchange for income?

I’m not a fan of financial complexity. ?Usually something goes wrong that the originators never imagined. ?I may not have thought of what will?go wrong here, but I’ve given you several avenues where this idea may go, so that you can avoid losing.