Photo Credit: ?Yiyo! || Politicians as a group are mortal; they might move the market in the short run, but in the long-run they have no impact

Whether Trump boasts over how well the stock market has done over his tenure, or Bloomberg notes how little the stock market has done over the last few years, both are wrong in placing emphasis on the stock market as a guide to evaluating a President or Congress. Why wrong? A number of reasons:

Time Measurement Problems

Though it is lost to the computer system at theStreet.com, in the Columnist Conversation, we once had a discussion over Presidents and the stock market. Measured by inauguration date, I provided a total return figure for each president back to FDR. Then we all proceeded, myself included, to explain why it was wrong.

Assuming a president does have a permanent effect on the market, when does it start and end? Markets are discounting mechanisms, and the changes in likelihood of being elected prior to the election might affect the market, as might the actions of the existing president, even if he is not on the ballot. How to separate those would be a challenge. Perhaps in hindsight we could make guesses when the eventual winner first polls over a majority of electoral or popular votes, but there would be troubles with this as well.

For another example, consider when a President is polling so badly that the market concludes he is a lame duck, and they expect the next president will be better or worse for the market. Who gets that performance?

Difficult to Separate President from Congress, and the Fed as well

The president isn’t the only actor that affects economic policy. Congress can propose its own agenda if it is united. It can help and/or hinder the agenda of the President.

Some analysts make a lot over a divided government, were neither of the main parties has full control. Divided governments come in two flavors: cooperative and hostile. Nixon, Reagan and Clinton were able to get a lot done in a divided government. For Obama and Trump, the hostility between the parties inhibited getting many new bills passed.

It’s also rare when the President has a Federal Reserve that cooperates fully with what he wants. There are a few Fed chairs that were like that: Greenspan, Burns and Miller. Given the lags in the effects from monetary policy, their actions left problems for the Presidents after their terms as Fed chair. The opposite was true for Fed chairs that took hard actions. They tended to hurt the current president’s economic agenda, while benefiting the next president.

My main point here is even if you measuring a president using the stock market, he’s not the only one affecting the stock market — it would be difficult to say what he was responsible for.

Factors outside of the government often affect the market more

Demographics, social change and technological change are things the President has very little effect on, and yet they have a large impact on markets. He should not receive the credit for things outside his control, positive or negative.

Policy has fleeting impacts and is often undone — all policy is temporary

Even if a President can enact policies that change things, the longest he will be in power is eight years. Given the frequent changes of what party the President comes from, even policies that are announced as permanent changes will likely be temporary. If you need proof of this, look at the tax code, which undergoes significant revision yearly.

Worse yet, many aspects of tax and spending laws are deliberately temporary in order to comply with deficit constraints. Don’t get me wrong, I am in favor of the constraints, just not temporary laws. You may as well not bother, and reduce the level of complexity. Predictability of laws and regulations tends to be an aid to planning, which aids growth.

Who cares about the market, anyway? A higher stock market isn’t necessarily better for the nation as a whole.

Just because the market is higher, or interest rates are lower does not mean that the nation as a whole is better off. A low cost of capital benefits future securities issuers, and reduces nominal income to future security purchasers. Warren Buffett has said that younger people should be rooting for lower security prices because it will give them higher returns for future investment.

For example, think of the State and municipal defined benefit plans that are choking on the lack of returns relative to what the sponsors imagined they would earn when they made the too expensive promises. On net, they would benefit from lower stock prices and higher interest rates.

The President doesn’t have that much effect on GDP either, but at least GDP is a little more neutral, taking into account all sources of returns not just interest and profits.

The Comment of Peter’s Grandfather

In the children’s music classic “Peter and the Wolf” at the end, Peter’s Grandfather who was proven wrong makes a statement to salvage a little pride, “Vot if Peter had not caught the Vulf. Vot den?” The question here would be, “Would Hillary have done any better as President? Would the stock market be lower or higher under her efforts?”

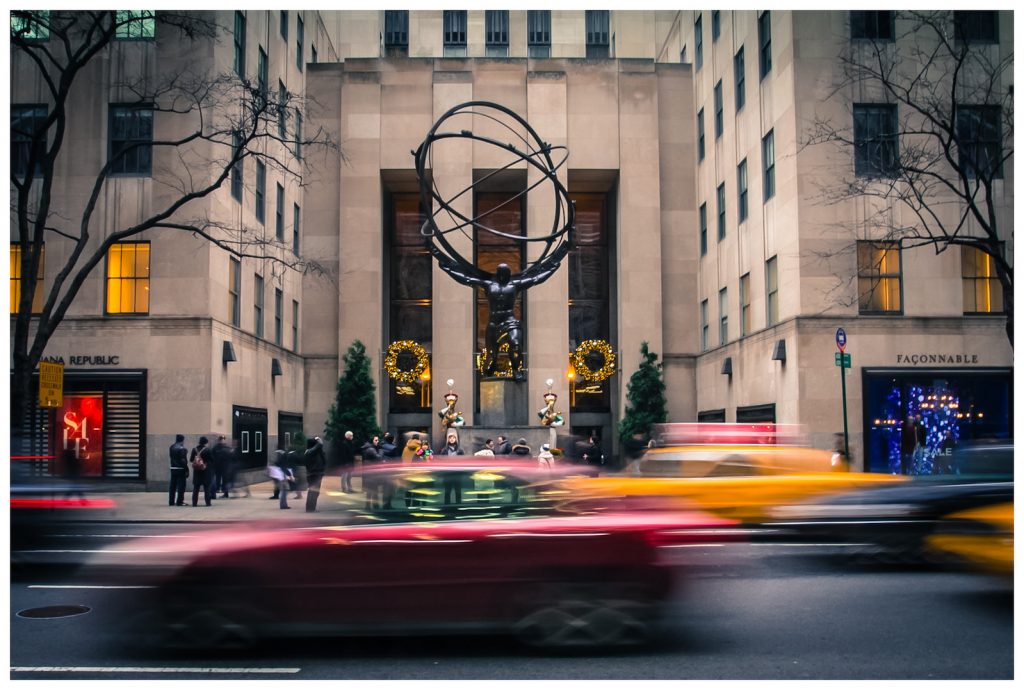

Even under conditions of perfection, we don’t have a “2017 Test Earth” to send Hillary Clinton to to see how well she would have fared as President. The stock market might have been higher under her than under Trump. After all, the Clintons were viewed by many Democrats to be pawns of Wall Street. On the other side, Trump is not much of a fan of Wall Street, being more of a borrower, rather than an investor in public securities.

And thus one of my points: there are so many things going on that we can’t tell whether the stock market would be higher or lower with Trump vs Clinton. Thus I will tell you that trying to analyze Trump or any other President via the stock market is a waste of time.

Summary

My points are threefold:

- We can’t tell how much impact a President has on the stock market.

- Even if we could, the stock market does not measure most of what a nation does, the happiness and security of its people, etc. It would be a poor measure of success for a President.

- We don’t even know whether the stock market being higher or lower is better.

If I could change the minds of my fellow Americans, I would tell them that politicians are ineffective in dealing with the economy. The government should set basic rules of fairness, and then not interfere much. The government can better spend its time on public health, internal security, defense, and its court systems. Then let the states handle variable local affairs.

If we did that, government could work on things that they can have an impact on. The economy is not one of those things, so don’t evaluate your politicians off of pocketbook issues. They can’t do anything about those. Rather, ask if they are the right people to take care of matters of justice.