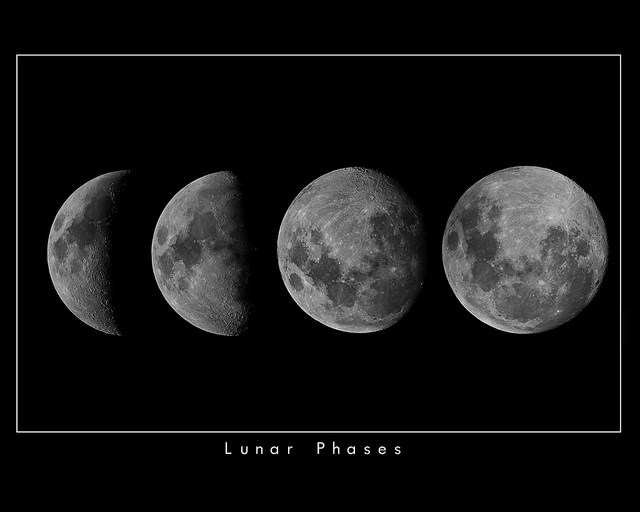

Sixteen Implications of “The Phases of an Investment Idea”

My last post has many implications. I want to make them clear in this post.

- When you analyze?a manager, look at the repeatability of his processes. ?It’s possible that you could get “the Big Short” right once, and never have another good investment idea in your life. ?Same for investors who are the clever ones who picked the most recent top or bottom… they are probably one-trick ponies.

- When a manager does well and begins to pick up a lot of new client assets, watch for the period where the growth slows to almost zero. ?It is quite possible that some of the great performance during the high growth period stemmed from asset prices rising due to the purchases of the manager himself. ?It might be a good time to exit, or, for shorts to consider the assets with the highest percentage of market cap owned as targets for shorting.

- Often when countries open up to foreign investment, valuations are relatively low. ?The initial flood of money in often pushes up valuations, leads to momentum buyers, and a still greater flow of money. ?Eventually an adjustment comes, and shakes out the undisciplined investors. ?But, when you look at the return series analyze potential future investment, ignore the early years — they aren’t representative of the future.

- Before an academic paper showing a way to invest that would been clever to use in the past gets published, the excess returns are typically described as coming from valuation, momentum, manager skill, etc. ?After the paper is published, money starts getting applied to the idea, and the strategy will do well initially. ?Again, too much money can get applied to a limited factor (or other) anomaly, because no one knows how far it can get pushed before the market rebels. ?Be careful when you apply the research — if you are late, you could get to hold the bag of overvalued companies. ?Aside for that, don’t assume that performance from the academic paper’s era or the 2-3 years after that will persist. ?Those are almost always the best years for a factor (or other) anomaly strategy.

- During a credit boom, almost every new type of fixed income security, dodgy or not, will look like genius by?the early purchasers. ?During a credit bust, it is rare for a new security type to fare well.

- Anytime you take a large position in an obscure security, it must jump through extra hoops to assure a margin of safety. ?Don’t assume that merely because you are off the beaten path that you are a clever contrarian, smarter than most.

- Always think about the carrying capacity of a strategy when you look at an academic paper. ?It might be clever, but it might not be able to handle a lot of money. ?Examples would include trying to do exactly what Ben Graham did in the early days today, and things like Piotroski’s methods, because typically only a few small and obscure stocks survive the screen.

- Also look at how an academic paper models trading and liquidity, if they give it any real thought at all. ?Many papers embed the idea that liquidity is free, and large trades can happen where prices closed previously.

- Hedge funds and other manager databases should reflect that some managers have closed their funds, and put them in a separate category, because new money can’t be applied to those funds. ?I.e., there should be “new money allowed” indexes.

- Max Heine, who started the Mutual Series funds (now part of Franklin), was a genius when he thought of the strategy 20% distressed investing, 20% arbitrage/event-driven investing and 60% value investing. ?It produced great returns 9 years out of 10. ?but once distressed investing and event-driven because heavily done, the idea lost its punch. ?Michael Price was clever enough to sell the firm to Franklin before that was realized, and thus capitalizing the past track record that would not?do as well in the future.

- The same applies to a lot of clever managers. ?They have a very good sense of when their edge is getting dulled by too much competition, and where the future will not be as good as the past. ?If they have the opportunity to sell, they will disproportionately do so then.

- Corporate management teams are like rock bands. ?Most of them never have a hit song. ?(For managements, a period where a strategy improves profitability far more than most would have expected.) ?The next-most are one-hit wonders. ?Few have multiple hits, and rare are those that create a culture of hits. ?Applying this to management teams — the problem is if they get multiple bright ideas, or a culture of success, it is often too late to invest, because the valuation multiple adjusts to reflect it. ?Thus, advantages accrue to those who can spot clever managements before the rest of the market. ?More often this happens in dull industries, because no one would think to look there.

- It probably doesn’t make sense to run from hot investment idea to hot investment idea as a result of all of this. ?You will end up getting there once the period of genius is over, and valuations have adjusted. ?It might be better to buy the burned out stuff and see if a positive surprise might come. ?(Watch margin of safety…)

- Macroeconomics and the effect that it has on investment returns is overanalyzed, though many get the effects wrong anyway. ?Also, when central bankers and politicians take cues from the prices of risky assets, the feedback loop confuses matters considerably. ?if you must pay attention to macro in investing, always ask, “Is it priced in or not? ?How much of it is priced in?”

- Most asset allocation work that relies on past returns is easy to do and bogus. ?Good asset allocation is forward-looking and ignores past returns.

- Finally, remember that some ideas seem?right by accident — they aren’t actually right. ?Many academic papers don’t get published. ?Many different methods of investing get tried. ?Many managements try new business ideas. ?Those that succeed get air time, whether it was due to intelligence or luck. ?Use your business sense to analyze which it might be, or, if it is a combination.

There’s more that could be said here. ?Just be cautious with new investment strategies, whatever form they may take. ?Make sure that you maintain a margin of safety; you will likely need it.