Numerator vs Denominator

Every now and then, a piece of good news gets announced, and then something puzzling happens. ?Example: the GDP report comes out stronger than expected, and the stock market falls. ?People scratch their heads and say, “Huh?”

A friend of mine who I haven’t heard from in a while, Howard Simons, astutely would comment something to the effect of: “The stock market is not a futures contract on GDP.” ?This much is true, but why is it true? ?How can the market go down on good economic news?

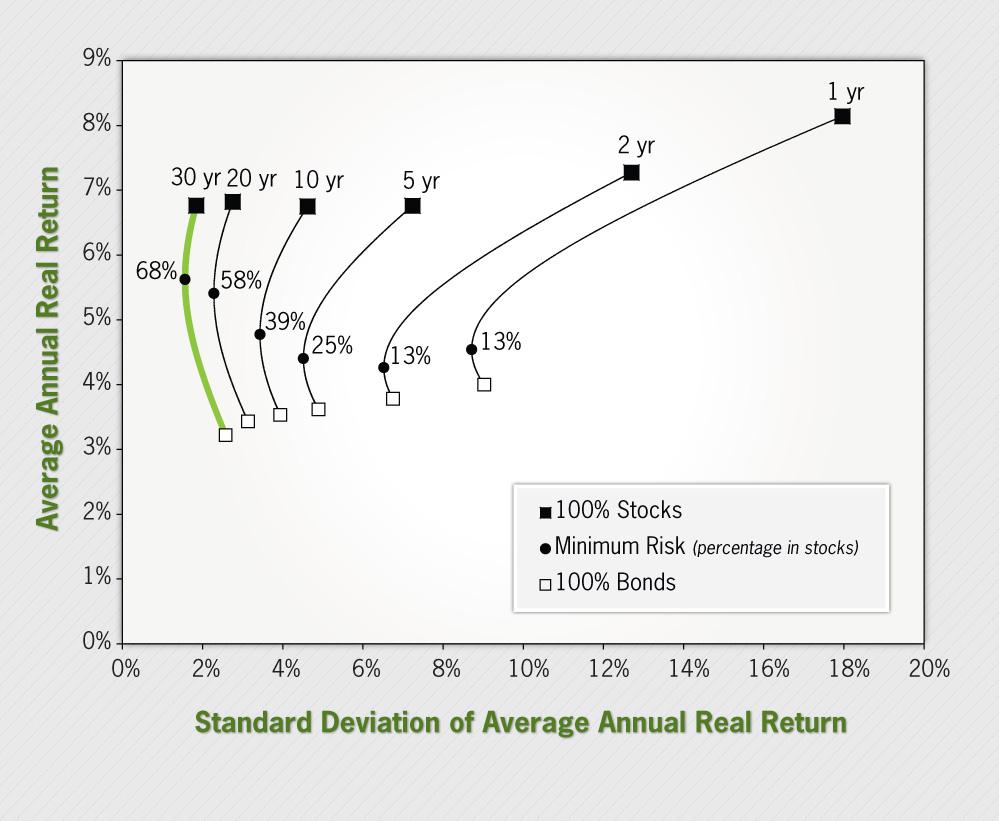

Some of us as investors use a concept called a discounted cash flow model. ?The price of a given asset is equal to the expected cash flows it will generate in the future, with each future cash flow?discounted to reflect to reflect the time value of money and the riskiness of that cash flow.

Think of it this way: if the GDP report comes out strong, we can likely expect corporate profits to be better, so the expected cash flows from equities in the future should be better. ?But if the stock market prices fall, it means the discount rates have risen more than the expected cash flows have risen.

Here’s a conceptual problem, then: We have estimates of the expected cash flows, at least going a few years out but no one anywhere publishes the discount rates for the cash flows — how can this be a useful concept?

Refer back to a piece I wrote earlier this week. ?Discount rates reflecting the cost of capital reflect the alternative sources and uses for free cash. ?When the GDP report came out, not only did come get optimistic about corporate profits, but perhaps realized:

- More firms are going to want to raise capital to invest for growth, or

- The Fed is going to have to tighten policy sooner than we?thought. ?Look at bond prices falling and yields rising.

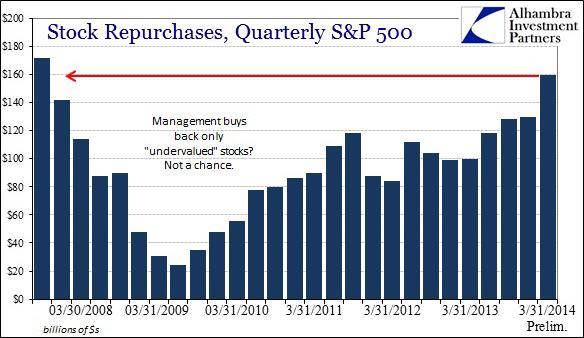

Even if things are looking better for?profits for existing firms, opportunities away from existing firms may improve even more, and attract capital away from existing firms. ?Remember how stock prices slumped for bricks-and-mortar companies during the tech bubble? ?Don’t worry, most people don’t. ?But as those prices slumped, value was building in those companies. ?No one saw it then, because they were dazzled by the short-term performance of the tech and dot-com stocks.

The cost of capital was exceptionally low for the dot-com stocks 1998-early?2000, and relatively high for the fuddy-duddy companies. ?The economy was doing well. ?Why no lift for all stocks? ?Because incremental dollars available for finance were flowing?to the dot-com companies until?it became obvious that little to no cash would ever flow back from them to investors.

Afterward, even as the market fell hard, many fuddy-duddy stocks didn’t do so badly. ?2000-2002 was a good period for value investing as people recognized how well the companies generated profits and cash flow. ?The cost of capital normalized, and many dot-coms could no longer get financing at any price.

Another Example

Sometimes people get puzzled or annoyed when in the midst of a recession, the stock market rises. ?They might think: “Why should the stock market rise? ?Doesn’t everyone?know that business conditions are lousy?”

Well, yes, conditions may be lousy, but what’s the alternative for investors for stocks? ?Bond yields may be falling, and inflation nonexistent, making money market fund yields microscopic… the relative advantage from a financing standpoint has?swung to stocks, and the prices rise.

I can give more examples, and maybe this should be a series:

- The Fed tightens policy and bonds rally. (Rare, but sometimes…)

- The Fed loosens policy, and bonds fall. (also…)

- The rating agencies downgrade the bonds, and they rally.

- The earnings report comes out lower than last year, and the stock rallies.

- Etc.

But perhaps the first important practical takeaway is this: there will always be seemingly anomalous behavior in the markets. ?Why? ?Markets are composed of people, that’s why. ?We’re not always predictable, and we don’t predict?better when you examine us as groups.

That doesn’t mean there is no reason for anomalies, but sometimes we have to take a step back and say something as simple as “good economic news means lower stock prices at present.” ?Behind that is the implied increase in the cost of capital, but since there is nothing to signal that, you’re not going to hear it on the news that evening:

“In today’s financial news, stock prices fell when the GDP report came out stronger than expected, leading investors to pursue investments in newly-issued bonds, stocks, and private equity.”

So be aware of the tone of the market. ?Today, bad news still seems to be good, because it means the Fed leaves interest rates low for high-quality short-term debt for a longer period than previously expected. ?Good news may imply that there are other places to attract money away from stocks.

Ideas for this topic are welcome. ?Please leave them in the comments.