Okay, Go Ahead, Sweat the Fed

Today, I happened to stumble across an old article of mine: Easy In, Hard Out (Updated). ?It’s kind of long, but goes into the changes that have happened at the Fed since the crisis, and points out why tightening policy might be tough. ?Nothing has changed in the 2.4 years since I wrote it, so I am going to reprint the end of the article. ?Let me know what you think.

-==-=-=–==-=–=-==-=-=-=-=-

In normal times, central banks buy only government debt, and keeps the assets relatively short, at longest attempting to mimic the existing supply of government debt.? Think of it this way, purchases/sales of longer debt injects/removes liquidity for longer periods of time.? Staying short maintains flexibility.

Yes, the Fed does not mark its securities or gold to market.? Under most scenarios, it is impossible for a central bank which can issue its own currency to go broke.? Rare exceptions ? home soil wars that fail, or political repudiation of the bank, where the government might create a new monetary standard, or closes the bank because of inflation.? (Hey, the central bank has been eliminated twice before.? It could happen again.)

The only real effect is on how much?seigniorage the Fed remits to the Treasury, or, if things go bad, how much the Treasury would have to lend/send to the central bank in order to avoid the bad optics of negative capital, perhaps via the Supplemental Financing Account.? This isn?t trivial; when people hear the central bank is ?broke,? they will do weird things.? To avoid that, the Fed?s gold will be revalued to market at minimum; hey maybe the Fed at that time will be the vanguard of market value accounting, and revalue everything.? Can you imagine what the replacement cost of the NY Fed building is?? The temple in DC?

Or, maybe the bank would be recapitalized by its member banks, if they are capable of doing so, with the reward being the preferred dividend they receive.

Back to the main point.? What effect will this abnormal monetary policy have in the future?

Scenarios

1) Growth strengthens and inflation remains low.? In this unusual combo, it will be easy?for the Fed to collapse its balance sheet, and raise rates.? This is the dream scenario; and I don?t think it is likely.? Look at the global economy; there is a lot of slack capacity.

2) Growth strengthens and inflation rises.? The Fed will likely raise the interest on reserves rate, but not sell bonds.? If they do sell bonds, the market will back up, and their losses will be horrible.? If don?t take the losses,?seigniorage could be considerably reduced, or even vanish, as the Fed funds rate rises, but because of the long duration asset portfolio, asset income rises slowly.? This is where the asset-liability mismatch bites.

If the Fed doesn?t raise the interest on reserves rate, I suspect banks would be willing to lend more, leaving fewer excess reserves at the Fed, which could stimulate more inflation. Now, there are some aspects of inflation that remain a mystery ? because sometimes inflationary conditions affect assets, rather than goods, I think depending on demographics.

3) Growth weakens and inflation remains low.? This would be the main scenario for QE4, QE5, etc.? We don?t care much about the Fed?s balance sheet until the Fed wants to raise rates, which is mainly a problem in Scenario 2.

4) Growth weakens and inflation rises, i.e. stagflation.? There?s no good set of policy options here. The Fed could engage in further financial repression, keeping short rates low, and let inflation reduce the nominal value of debts.? If it doesn?t run wild, it could play a role in reducing the indebtedness of the whole economy, though again, it will favor debtors over savers.? (As I?ve said before, in a situation like this, or like the Eurozone, all creditors want to be paid back at par on the bad loans that they have made, and it can?t be done.? The pains of bad debt have to go somewhere, where it goes is the argument.)

I?ve kept this deliberately simple, partially because with all of the flows going back and forth, and trying to think of the whole system, rather than effects on just one part, I know that I have glossed over a lot.? I accept that, and I could be dead wrong, as I sometimes am.? Comment as you like, with grace and dignity, and let us grow together in our knowledge.? I?ve been spending some time reading documents at the Fed, trying to understand their mechanisms, but I could always learn more.

Summary

During older times, the end of a Fed loosening cycle would end with the Fed funds rate rising.? In this cycle, it will end with interest of reserves rising, and/or, the sale of bonds, which I find less likely (they will probably be held to maturity, absent some crisis that we can?t imagine, or non-inflationary growth).? But when the tightening cycle comes, the Fed will find that its actions will be far harder to take than when they made the ?policy accommodation.?? That has always been true, which is why the Fed during its better times limited the amount of stimulus that it would deliver, and would tighten sooner than it needed to.

Far better to be like McChesney Martin or Volcker, and be tough, letting recessions do their necessary work of eliminating bad debt.? Under Greenspan, and Bernanke to a lesser extent (though he persists in pushing the canard that the Fed was not too loose 2003-2004, ask John Taylor for more), there were many missed opportunities to stop the buildup of bad debts, but the promise of the ?Great Moderation? beguiled so many.

Removing policy accommodation is always tougher than imagined, and carries new risks, particularly when new tools have been used.? Bernanke can go to his carefully chosen venues and speak to his carefully chosen audiences, and try to exonerate the Fed from well-deserved blame for their looseness in the late 80s, 90s, and 2000s.? Please, Mr. Bernanke, take some blame there on behalf of the Fed ? the credit boom could never have happened without the Fed.? Painting the Fed as blameless is wrong; the ?Greenspan put? landed us in an overleveraged bust.

I?m not primarily blaming the Fed for its current conduct; we are still in the aftermath of a lending bust ? too much bad mortgage debt, with a government whose budget is out of balance.? (In the bust, there are no good solutions.)? I am blaming the Fed for loose policies 1984-2007, monetary policy should have been a lot tighter on average.? But now we live with the results of prior bad policy, and may the current Fed not compound it.

Postscript

The main difference between this time and the last time I wrote on this is QE3.? What has been the practical impact since then?? The Fed owns more MBS and long maturity Treasuries, financed by more reserve balances at the Fed.

Banks use this cheap funding to finance other assets.? But if they want to make money, the banks have to take credit risk (something the Fed is trying to stimulate), and/or interest rate rate risk (borrow short, lend long, negative convexity, etc).? The longer low rates go on through interest on reserves, the greater the tendency to build up imbalances in the banking system through credit and interest rate risks. 1992-1993 where Fed funds rates were held at 3%, was followed by the residential mortgage backed security market melting down in 1994, not to mention Mexico.? Sub-2% Fed funds rates from 2002 through mid-2004 led to massive overinvestment in residential housing, leading to the present crisis.

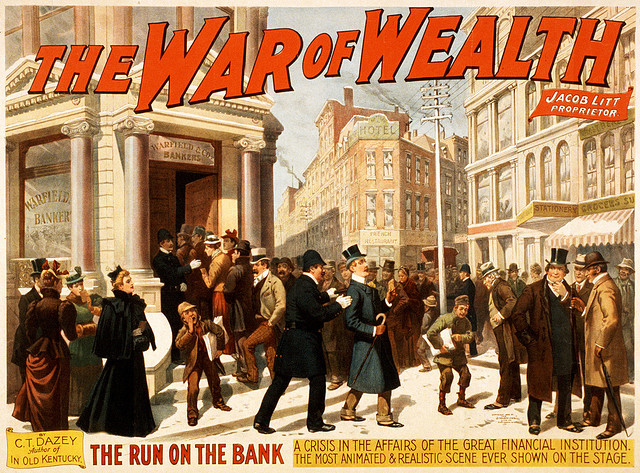

Fed tightening cycles often start with a small explosion where short-dated financing for thinly capitalized speculators evaporates, because of the anticipation of higher financing rates.? Fed tightening cycles often end with a large explosion, where a large levered asset class that was better financed, was not financed well-enough.? Think of commercial property in 1989, the stock market in 2000 (particularly the NASDAQ), or housing/banks in 2008.? And yet, that is part of what Fed policy is supposed to do: reveal parts of the economy that are running too hot, so that capital can flow from misallocated areas to areas that are more sound.? At present, my suspicion is that we still have more trouble to come in banking sector.? Here?s why:

We?ve just been through 4.5 years of Fed funds / Interest on reserves being below 0.5% ? this is a far greater period of loose policy than that of 1992-1993 and 2002 to mid-2004 together, and there is no apparent end in sight.? This is why I believe that any removal of policy accommodation will prove very difficult.? The greater the amount of policy accommodation, the greater the difficulties of removal.? Watch the fireworks, if/when they try to remove it.? And while you have the opportunity now, take some risk off the table.