The Importance of Your Time Horizon

I ran across two interesting articles today:

- Volatility Doesn’t Equal Loss?Unless You Sell?from Oppenheimer Funds, and

- Buying the Dips Doesn?t Work for Everyone?by the estimable Jason Zweig.

Both articles are exercises in understanding the time horizon over which you invest. ?If you are older, you may not have the time to recover from market shortfalls, so advice to buy dips may sound hollow when you are nearer to drawing on your assets.

Thus the idea that volatility, presumably negative, doesn’t hurt unless you sell. ?Some people don’t have much choice in the matter. ?They have retired, and they have a lump sum of money that they are managing for long-term income. ?No more money is going in, money is only going out. ?What can you do?

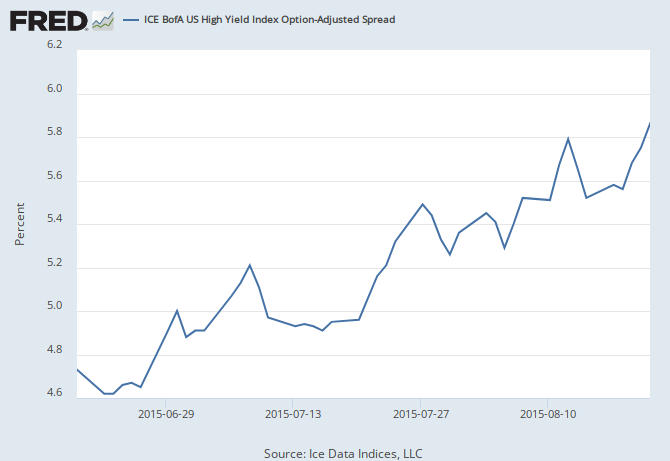

You have to plan before volatility strikes. ?My equity only clients had 14% cash before the recent volatility hit. ?Over the past week I opportunistically brought that down to 10% in names that I would like to own even if the “crisis” deepened. ?That flexibility was built into my management. ?(If the market recovers enough, I will rebuild the buffer. ?Around 1300 on the S&P, I would put all cash to work, and move to the alternative portfolio management strategy where I sell the most marginal ideas one at a time to raise cash and reinvest into the best ideas.)

If an older investor would be?hurt by a drawdown in the stock market, he needs to invest less in stocks now, even if that means having a lower income on average over the longer-term. ?With a higher level of bonds in the portfolio, he could more than?proportionately draw down on bonds during a crisis, which would rebalance his portfolio. ?If and when the stock market recovered, for a time, he could draw on has stock positions more than proportionately then. ?That also would rebalance the portfolio.

Again, plans like that need to be made in advance. ?If you have no plans for defense, you will lose most wars.

One more note: often when we talk about time horizon, it sounds like we are talking about a single future point in time. ?When the time for converting assets to cash is far distant, using a single point may be a decent approximation. ?When the time for converting assets to cash is near, it must be viewed as a stream of payments, and whatever scenario testing, (quasi)?Monte Carlo simulations, and sensitivity analyses are done must reflect that.

Many different scenarios may have the same average rate of return, but the ones with early losses and late gains are pure poison to the person trying to manage a lump sum in retirement. ?The same would apply to an early spike in inflation rates followed by deflation.

The time to plan is now for all contingencies, and please realize that this is an art and not a science, so if someone comes to you with glitzy simulation?analyses, ask them to run the following scenarios: run every 30-year period back as far as the data goes. ?If it doesn’t include the Great Depression, it is not realistic enough. ?Run them forwards, backwards, upside-down forwards, and upside-down backwards. ?(For the upside-down scenarios normalize the return levels to the right side up levels.) ?The idea here is to use real volatility levels in the analyses, because reality is almost always more volatile than models using normal distributions. ?History is meaner, much meaner than models, and will likely be meaner in the future… we just don’t know how it will be meaner.

You will then be surprised at how much caution the models will indicate, and hopefully those who can will save more, run safer asset allocations, and plan to withdraw less over time. ?Reality is a lot more stingy than the models of most financial Dr. Feelgoods out there.

One more note: and I know how to model this, but most won’t — in the Great Depression, the returns after 1931 weren’t bad. ?Trouble is, few were able to take advantage of them because they had already drawn down on their investments. ?The many bankruptcies meant there was a smaller market available to invest in, so the dollar-weighted returns in the Great Depression were lower than the buy-and-hold returns. ?They had to be lower, because many people could not hold their investments for the eventual recovery. ?Part of that was margin loans, part of it was liquidating assets to help tide over unemployment.

It would be wonky, but simulation models would have to have an uptick in need for withdrawals at the very time that markets are low. ?That’s not all that much different than some had to do in the recent financial crisis. ?Now, who is willing to throw *that* into financial planning models?

The simple answer is to be more conservative. ?Expect less from your investments, and maybe you will get positive surprises. ?Better that than being negatively surprised when older, when flexibility is limited.