Unstable Value Funds (VI)

Photo Credit: Ruin Raider || It is important to recognize the limitations of any system. Don’t overestimate what is possible.

Well, the last installment in this series was 2009. I ran a Guaranteed Investment Contract [GIC] desk at Provident Mutual from 1992-1997. I also managed our internal stable value funds for our pension line of business. This was during a period where increasingly Stable Value Funds were being replaced by bonds and bond funds being wrapped by a type of derivative that would allow for “benefit responsive payments,” called a “wrap contract.”

Now, I know I lost most of you with the last paragraph. Definitions:

Guaranteed Investment Contract: A group annuity issued by a life insurance company. It is like a bond, paying principal and interest until it matures. But it is more secure than most bonds because it is an insurance liability, which has a higher bankruptcy priority than a bond issued by the insurance company. Also, a GIC will pay money out sooner if there is a need to pay “benefit responsive payments.” Absent default, the value of a GIC never falls. Its value accrues like a savings account, because it is an annuity from a life insurer.

Benefit Responsive Payments: In Defined Contribution Pension Plans (401k, 403b, 457, etc.), if a participant dies, gets disabled, leaves his current employer, gets served with a QDRO [Qualified Domestic Relations Order — child support, alimony], exchanges funds in the stable value fund for noncompeting funds (funds that are not short-to-intermediate fixed income), etc., then the GIC may pay benefits out early at book value.

Stable Value Funds: Funds that buy investments that absent default, only appreciate, and thus act like a savings account, but with much better yields. Those can be insurance contracts (rare now), or bonds wrapped by “wrap agreements.”

Wrap Agreements: Derivative instruments that receive money if benefit responsive payments occur and the market value of the wrapped bonds is higher than the book value, and pay money if benefit responsive payments occur and the market value of the wrapped bonds is lower than the book value. The objective is that benefit responsive payments go to the beneficiary at book value, and no one else in the Stable Value Fund is affected.

Why am I Writing This?

I received an email from a lady working at a major investment bank, asking me where she could find independent commentary regarding stable value funds, because most of the commentary is produced by the stable value fund managers themselves. Why is that so? Stable Value Funds are complex beasts. Typically only insiders understand them. She was wondering how the funds were doing given the rapid increase in interest rates. This is the toughest scenario for stable value funds.

The Math

Let’s define terms first.

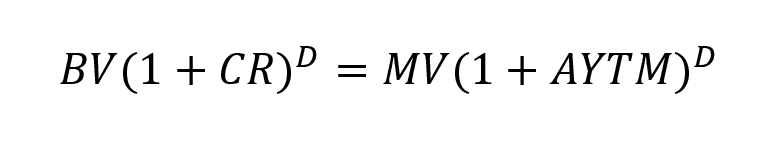

BV: Book value — the accrued value of the stable value fund assets so far.

MV: Market Value — the market value of the assets now, if we are able to liquidate the assets at current prices.

AYTM: Annualized Yield to Maturity — the annualized rate that the assets are yielding at current market prices. Note that if you have the SEC Yield, that is the Semiannual yield to maturity, sometimes called the bond-equivalent yield [YTM]. To convert YTM to AYTM:((1 + YTM/2)^2) -1 = AYTM.

D: Effective Duration — The first derivative of Market Value with respect to AYTM. For those that have not taken Calculus, or have forgotten what that means, it measures the sensitivity of market value to small moves in the AYTM. A bigger D means the market value changes more than a smaller D. (And always remember, as interest rates rise, the value of all ordinary bonds goes down.

It is called effective duration, because on a present value basis it measures the weighted average time at which you can expect to receive the cash flows, typically measured in years.

CR: Credited Rate — Though all of these values are artificial in some sense (channeling my best Matt Levine), this one is the most artificial. It means this: in the past the book value accrued to its current value. Now, over the length of time expressed by the Effective Duration, what should the current credited rate be in order for the book and market value to converge? The credited rate is a figure that is like a “heat-seeking” missile, always adjusting (monthly or quarterly) to new conditions as the book value chases the market value. When book value is above market value, the credited rate slows down relative to the AYTM. When the book value is below the market value, the credited rate speeds up relative to the AYTM.

So what’s the issue here?

Interest rates have risen rapidly, after dwelling at low rates for a long time. Back when I was developing a stable value product in 1996, I knew this was the disaster scenario for stable value. More than most actuaries at the time, I had realistic interest rate scenario models the reflected the true volatility of interest rates. I would create 10,000 full yield curve scenarios over a 10 year period, then analyze the ones where the stable value fund failed. Failures occurred in the scenarios where short rates rose rapidly.

Wait. How can a stable value fund fail? If the credited rate drops below zero, practically it has failed. The fund sponsor will credit zero in such a situation, but it will face the problem of participants exiting to non-competing options, worsening the problem. The stable value fund may not be able to return book value to its participants.

But this isn’t bad for everyone, at least not yet

I don’t think everyone needs to worry, though. The edge cases, those who have taken too much risk at the wrong time should worry. for the worst-managed funds, there is some risk of a “run-on-the fund.”

I did a little digging around the large stable value managers, at least among those who publish all their data publicly. I’m not naming names, I have my own liability risk here. There are a number of insurance companies running their stable value plans at durations higher than 5, and their ratio of market value to book value is near 85%. If you are in such a situation, move your stable value assets to a balanced fund for 30 days, then move that to a short-to-intermediate term bond fund. You will escape the low-yielding and possibly defaulting stable value fund. You will also earn more from the bond fund.

At present, most stable value funds have a market value to book value is between 91-95%. If you are in a fund like that, don’t worry, unless a panic happens because of the funds running at long durations. Then do the same shuffle that I suggest: move your stable value assets to a balanced fund for 30 days, then move that to a short-to-intermediate term bond fund. You will escape the low-yielding and possibly defaulting stable value fund. You will also earn more from the bond fund.

Other Issues

There is also the risk of stretching for yield. Though the bond managers who manage fixed-income portfolios for stable value funds are generally conservative, when rates are low, many bond managers take chances that don’t work out. As such if the YTM/AYTM of the asset manager seems aggressive, maybe pare back. (If it is more than 1.5% above Treasuries, consider leaving.) If something seems too good to be true, it very well may be too good to be true.

Conclusion

Say what you will about Stable Value Funds, they are more opaque than other investments. As such, they deserve more scrutiny. It is not a bad idea now for most participants to move your stable value assets to a balanced fund for 30 days, then move that to a short-to-intermediate term bond fund. You will escape the low-yielding and possibly defaulting stable value fund. You will also earn more from the bond fund.

I don’t think most people have to do this, but it is not a bad strategy for all. Take your opportunity and move stable value money to a balanced fund. Then if you don’t like the volatility, move to a short-to-intermediate term bond fund.

![Welcome Back to 1994! [Redux]](https://alephblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/mortgage-rates.png)