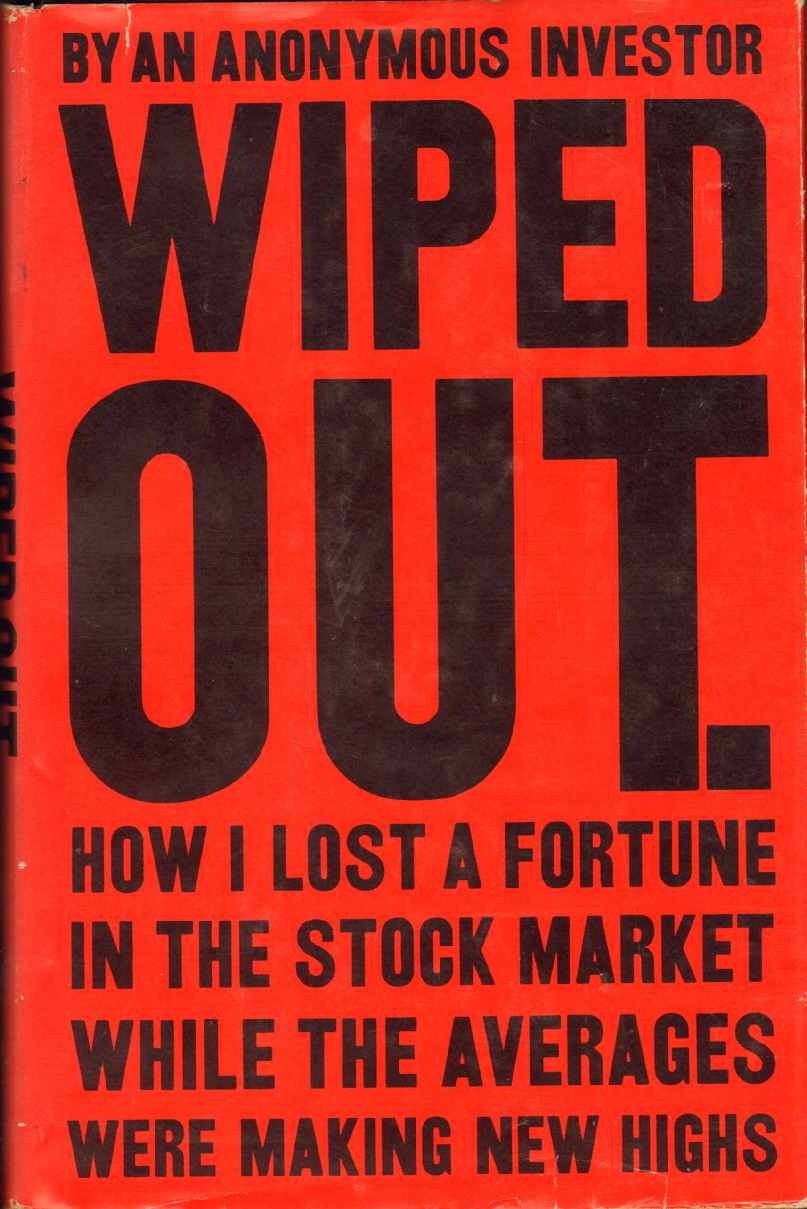

Book Review: Wiped Out

Before I start this evening, thanks to Dividend Growth Investor for telling me about this book.

This is an obscure little book published in 1966. ?The title is direct, simple, and descriptive. ?A more flowery title could have been, “Losing Money in the Stock Market as an Art Form.” ?Why? ?Because he made every mistake possible in an era that favored stock investment, and managed to lose a nice-sized lump sum that could have been a real support to his family. ?Instead, he tried to recoup it by anonymously publishing ?this short book which goes from tragedy to tragedy with just enough successes to keep him hooked.

Whom God Would Destroy

There is a saying, “”Whom the gods would destroy, they first make mad.” ?My modification of it is, “Whom God would destroy, he first makes proud.” ?In this book, the author knows little about investing, but wishing to make more money in the midst of a boom, he entrusts a sizable nest egg for a young middle-class family to a broker, and lo and behold, the broker makes money in a rising market with a series of short-term investments, with very few losses.

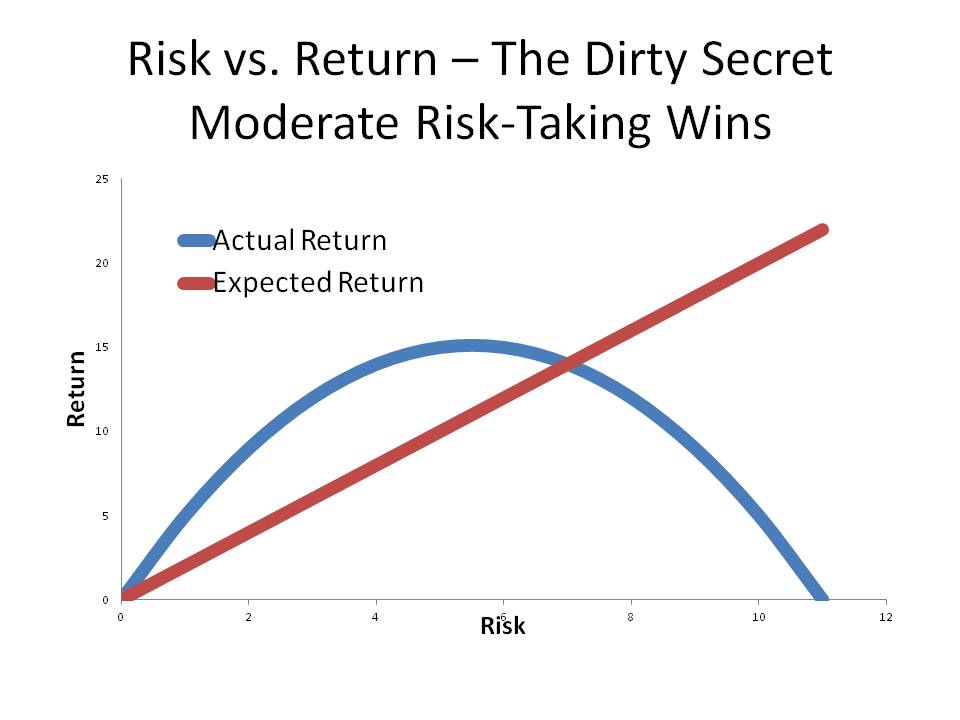

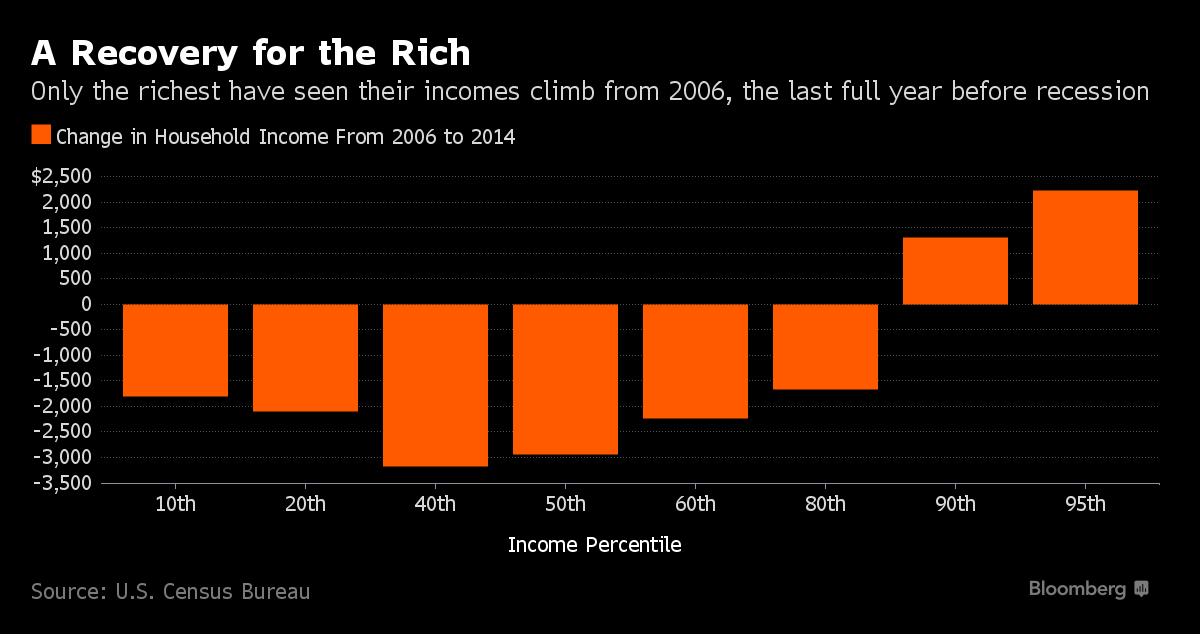

Rather than be grateful, the author got greedy. ?Spurred by success, he became somewhat compulsive, and began reading everything he could on investing. ?To brokers, he became “the impossible client,” (my words, not those of the book) because now he could never be satisfied. ?Instead of being happy with a long-run impossible goal of 15%/year (double your money every five years), he wanted to double his money every 2-3 years. (26-41%/year)

As such, he moved his money from the broker that later he admitted he should have been satisfied with, and sought out brokers that would try to hit home runs. ?The baseball analogy is useful here, because home run hitters tend to strike out a lot. ?The analogy breaks down?here: a home run hitter can be useful to a team even if he has a .250 average and strikes out three times for every home run. ?Baseball is mostly a game of team compounding, where usually a number of batters have to do well in order to score. ?Investment is a game of individual compounding, where strikeouts matter a great deal, because losses of capital are very difficult to make up. ?Three 25% losses followed by a 100% gain is a 15% loss.

In the process of trying to win big, he ended up losing more and more. ?He concentrated his holdings. ?He bought speculative stocks, and not “blue chips.” ?He borrowed money to buy more stock (used margin). ?He bought “story stocks” that did not possess a margin of safety, which would maybe deliver high gains ?if the story unfolded as illustrated. ?He did not do homework, but listened to “hot tips” and invested off them. ?He let his judgment be clouded by his slight relationships with corporate insiders at the end. ?HE TRIED TO MAKE BIG MONEY QUICKLY, AND CUT EVERY CORNER TO DO SO. ?His expectations were desperately unrealistic, and as a result, he lost it all.

As he lost more and more, he fell into the psychological trap of wanting to get back what he lost, and being willing to lose it all in order to do so. ?I.e., if he lost so much already, it was worth losing what was left if there was a chance to prove he wasn’t a fool from his “investing.” ?As such, he lost it all… but there are three good things to say about the author:

- He had the humility to write the book, baring it all, and he writes well.

- He didn’t leave himself in debt at the end, but that was good providence for him, because if he had waited one more day, the margin clerk would have sold him out at a decided loss, and he would have owed the brokerage money.

- In the end, he knew why he had gone wrong, and he tells his readers that they need to: a) invest in quality companies, b) diversify, and c) limit speculation to no more than 20% of the portfolio.

His advice could have been better, but at least he got the aforementioned ideas?right. ?Margin of safety is the key. ?Doing significant due diligence if you are going to buy individual stocks is required.

Quibbles

This book will not teach you what to do; it teaches what not to do. ?It is best as a type of macabre financial entertainment.

Also, though you can still buy used copies of the book, if enough of you try to buy the used books out there, the price will rise pretty quickly. ?If you can, borrow it from interlibrary loan. ?It is an interesting historical curiosity of a book, and a cautionary tale for those who are tempted to greed. ?As the author closes the book:

“Cupidity is seldom circumspect.”

And thus, much as the greedy need to hear this advice, it is unlikely they will listen. ?Greed is compulsive.

Summary / Who Would Benefit from this Book

A good book, subject to the above limitations. ?It is best for entertainment, because it will teach you what not to do, rather than what to do.

Borrow it through interlibrary loan. ?If you feel you have to buy it, you can buy it here:?WIPED OUT. How I Lost a Fortune in the Stock Market While the Averages Were Making New Highs.

Full disclosure:?I bought it with my own money for three bucks.

If you enter Amazon through my site, and you buy anything, including books, I get a small commission. This is my main source of blog revenue. I prefer this to a ?tip jar? because I want you to get something you want, rather than merely giving me a tip. Book reviews take time, particularly with the reading, which most book reviewers don?t do in full, and I typically do. (When I don?t, I mention that I scanned the book. Also, I never use the data that the PR flacks send out.)

Most people buying at Amazon do not enter via a referring website. Thus Amazon builds an extra 1-3% into the prices to all buyers to compensate for the commissions given to the minority that come through referring sites. Whether you buy at Amazon directly or enter via my site, your prices don?t change.