Book Review: The Art of Execution

Some books are better in concept than they are in execution. ?Ironically, that is true of “The Art of Execution.”

The core idea of the book is that most great investors get more stocks wrong than they get right, but they make money because they let their winners run, and either cut their losses short or reinvest in their losers at much lower prices than their initial purchase?price. ?From that, the author gets the idea that the buy and sell disciplines of the investors are the main key to their success.

I know this is a book review, and book reviews are not supposed to be about me. ?I include the next two paragraphs to explain why I think the author is wrong, at least in the eyes of most investment managers that I know.

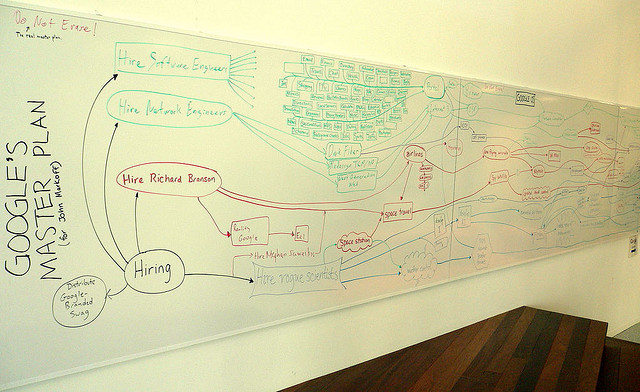

From my practical experience as an investment manager, I can tell you that your strategy for buying and selling?is a part of the investment process, but it is not the main one. ?Like the author, I also have hired managers to run a billion-plus dollars of money for a series of multiple manager funds. ?I did it for the pension division of mutual life insurer that no longer exists back in the 1990s. ?It was an interesting time in my career, and I never got the opportunity again. ?In the process, I interviewed a large number of the top long-only money managers in the US. ?Idea generation was the core concept for almost all of the managers. ?Many talked about their buy disciplines at length, but not as a concept separate from the hardest part of being a manager — finding the right assets to buy.

Sell disciplines received far less emphasis, and for most managers, were kind of an afterthought. ?If you have good ideas, selling assets is an easy thing — if your ideas aren’t good, it’s hard. ?But then you wouldn’t be getting a lot of assets to manage, so it wouldn’t matter much.

Much of the analysis of the author stems from the way he had managers run money for him — he asked them to invest on in their ten best ideas. ?That’s a concentrated portfolio indeed, and makes sense if you?are almost certain in your analysis of the stocks that you invest in. ?As such, the book spends a lot of time on how the managers traded single ideas as separate from the management of the portfolio as a whole. ?As such, a number of examples that he brought out as bad management by one set of managers sound really?bad, until you realize one thing: they were all part of a broader portfolio. ?As managers, they might not have made significant adjustments to a losing position because they were occupied with other more consequential positions that were doing better. ?After all, losses on a stock are capped at 100%, while gains are theoretically infinite. ?As a stock falls in price, if you don’t add to the position, the risk to the portfolio as a whole gets less and less.

Thus, as you read through the book, you get a collection of anecdotes to illustrate good and bad position and money management. ?Any one of these might sound bright or dumb, but they don’t mean a lot if the rest of the portfolio is doing something different.

This is a short book. ?The pages are small, and white space is liberally interspersed. ?If this had been a regular-sized book, with white space reduced, it might have taken up 80-90 pages. ?There’s not a lot here, and given the anecdotal nature of what was written, it is?not much more than the author’s opinions. ?(There are three pages citing an academic paper, but they exist as an afterthought in a chapter on one class of investors. It has the unsurprising result that positions that managers weight heavily do better than those with lower weights.) ? As such, I don’t recommend the book, and I can’t think of a subset of people that could benefit from it, aside from managers that want to be employed by this guy, in order to butter him up.

Quibbles

The end of the book mentions liquidity as a positive factor in asset selection, but most research on the topic gives a premium return to illiquid stocks. ?Also, if the manager has concentrated positions in the stocks that he owns, his positions will prove to be less liquid than less concentrated positions in stocks with similar tradable float.

Summary / Who Would Benefit from this Book

Don’t buy this book. ?To reinforce this point, I am not leaving a link to the book at Amazon, which I ordinarily do.

Full disclosure:?I?received a?copy from a PR flack.

If you enter Amazon through my site, and you buy anything, including books,?I get a small commission.? This is my main source of blog revenue.? I prefer this to a ?tip jar? because I want you to get something you want, rather than merely giving me a tip.? Book reviews take time, particularly with the reading, which most book reviewers don?t do in full, and I typically do. (When I don?t, I mention that I scanned the book.? Also, I never use the data that the PR flacks send out.)

Most people buying at Amazon do not enter via a referring website.? Thus Amazon builds an extra 1-3% into the prices to all buyers to compensate for the commissions given to the minority that come through referring sites.? Whether you buy at Amazon directly or enter via my site, your prices don?t change.