Gundlach vs Morningstar

I’ve been on both sides of the fence. ?I’ve been a bond manager, with a large, complex (and illiquid) portfolio, and I have been a selector of managers. ?Thus the current squabble between Jeffrey Gundlach and Morningstar isn’t too surprising to me, and genuinely, I could side with either one.

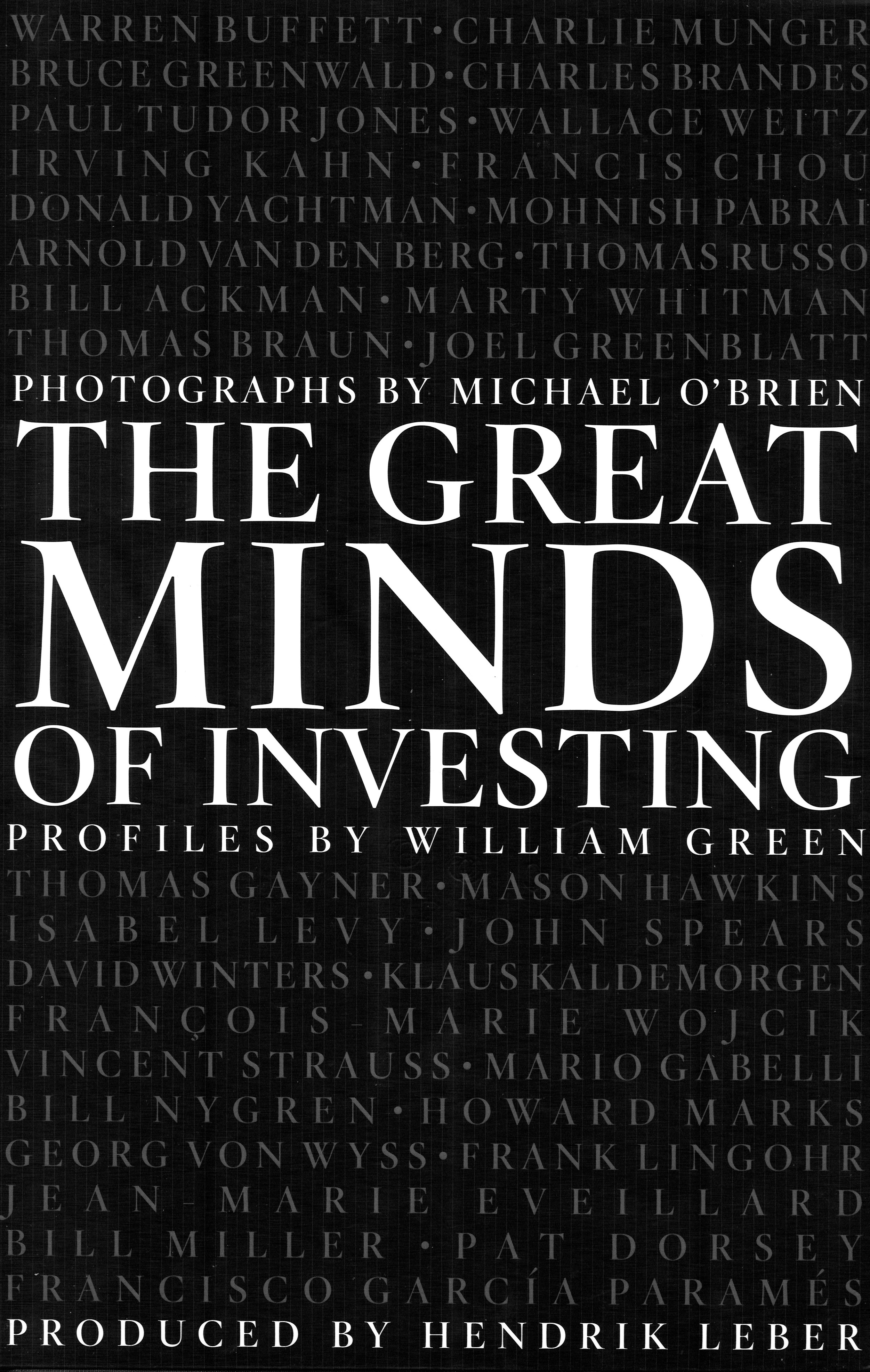

Let me take Gundlach’s side first. ?If you are a bond manager, you have to be fairly bright. ?You need to understand the understand the compound interest math, and also how to interpret complex securities that come in far more flavors than common stocks. ?This is particularly true today when many top managers are throwing a lot of derivative instruments into their portfolios, whether to earn returns, or shed risks. ?Aspects of the lending markets that used to be the sole province of the banks and other lenders are now available for bond managers to buy in a securitized form. ?Go ahead, take a look at any of the annual reports from Pimco or DoubleLine and get a sense of the complexity involved in running these funds. ?It’s pretty astounding.

So when the fund analyst comes along, whether for a buy-side firm, an institutional fund analyst, or retail fund analyst who does more than just a little number crunching, you realize that the fund analyst?likely knows less about what you do than one of your junior analysts.

One of the issues that Morningstar had ?was with DoubleLine’s holdings of?nonagency residential mortgage-backed securities [NRMBS]. ?These securities lost a lot of value 2007-2009 during the financial crisis. ?Let me describe what it was like in a chronological list:

- 2003 and prior: NRMBS is a small part of the overall mortgage bond market, with relatively few players willing to take credit risk instead of buying mortgage bonds guaranteed by Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie. ?Much of the paper is in the hands of specialists and some life insurance companies.

- 2004-2006 as more subprime lending goes on amid a boom in housing prices, credit quality standards fall and life insurance buyers slowly?stop purchasing the securities. ?A new yield-hungry group of buyers take their place, with not much focus on what could go wrong.

- Parallel to this, a market in credit derivatives grows up around the NRMBS market?with more notional exposure than the underlying market. ?Two sets of players: yield hogs that need to squeeze more income out of their portfolios, and hedge funds seeing the opportunity for a big score when the housing bubble pops. ?At last, a way to short housing!

- 2007: Pre-crisis, the market for NRMBS starts to sag, but nothing much happens. ?A few originators get into trouble, and a bit of risk differentiation comes into a previously complacent market.

- 2008-2009: the crisis hits, and it is a melee. ?Defaults spike, credit metrics deteriorate, and housing prices fall. ?Many parties sell their bonds merely to get rid of the taint in their portfolios. ?The credit derivatives exacerbate a bad situation. ?Prices on many NRMBS fall way below rational levels, because there are few traditional buyers willing to hold them. ?The regulators of financial companies and rating agencies are watching mortgage default risk carefully, so most regulated financial companies can’t hold the securities without a lot of fuss.

- 2010+ Nontraditional buyers like flexible hedge funds develop expertise and buy the NRMBS, as do some flexible bond managers who have the expertise in?staff skilled in analyzing the creditworthiness of bunches of securitized mortgages.

Now, after a disaster in a section of the bond market, the recovery follows a pattern like triage. ?Bonds get sorted into three buckets: those likely to yield a positive return on current prices, those likely to yield a negative return on current prices, and those?where you can’t tell. ?As time goes along, the last two buckets shrink. ?Market players revise prices down for the second bucket, and securities in the third bucket typically join one of the other two buckets.

Typically, though, lightning doesn’t strike twice. ?You don’t get another crisis event that causes that class of?securities to become disordered again, at least, not for a while. ?We’re always fighting the last war, so if credit deterioration is happening, it is in a new place.

And thus the problem in talking to the fund analyst. ?The securities were highly risky at one point, so aren’t they risky now? ?You would like to say, “No such thing as a bad asset, only a bad price,” but the answer might sound too facile.

Only a few managers devoted the time and effort to analyzing these securities after the crisis. ?As such, the story doesn’t travel so well. ?Gundlach already has a lot of money to manage, and more money is flowing in, so he doesn’t have to care whether Morningstar truly understands what DoubleLine does or not. ?He can be happy with a slower pace of asset growth, and the lack of accolades which might otherwise go to him…

But, one of the signs of being truly an expert is being able to explain it to lesser mortals. ?It’s like this story of the famous physicist Richard Feynman:

Feynman was a truly great teacher. He prided himself on being able to devise ways to explain even the most profound ideas to beginning students. Once, I said to him, “Dick, explain to me, so that I can understand it, why spin one-half particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics.” Sizing up his audience perfectly, Feynman said, “I’ll prepare a freshman lecture on it.” But he came back a few days later to say, “I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t reduce it to the freshman level. That means we don’t really understand it.”

Like it or not, the Morningstar folks have a job to do, and they will do it whether DoubleLine cooperates or not. ?As in other situations in the business world, you have a choice. ?You could task smart subordinates to spend adequate time teaching the Morningstar analyst your thought processes, or, live with the results of someone who fundamentally does not understand what you do. ?(This applies to bosses as well.)

In the end, this may not matter to DoubleLine. ?They have enough assets to manage, and then some. ?But in the end, this could matter to Morningstar. ?It says a lot if you can’t analyze one of the best funds out there. ?That would mean you really don’t understand well the fixed income business as it is presently configured. ?As such, I would say that it is incumbent on Morningstar to take the initiative, apologize to DoubleLine, and try to re-establish good communications. ?If they don’t, the loss is Morningstar’s, and that of their subscribers.