One Dozen Thoughts on Dealing with Risk in Investing for Retirement

Investing is difficult. That said, it can be harder still. Let people with little to no training to try to do it for themselves. Sadly, many people get caught in the fear/greed cycle, and show up at the wrong time to buy and/or sell. They get there late, and then their emotions trick them into action. A rational investor would say, ?Okay, I missed that move. Where are opportunities now, if there are any at all??

Investing can be made even more difficult. ?Investing reaches its most challenging level when one relies on his investing to meet an anticipated and repeated need for cash outflows.

Institutional investors will say that portfolio decisions are almost always easier when there is more cash flowing in than flowing out. ?It means that there is one dominant mode of thought: where to invest?new money? ?Some attention will be given to managing existing assets ? pruning away assets with less potential, but the need won?t be as pressing.

What?s tough is trying to meet a?cash withdrawal?rate that is materially higher than what can safely be achieved over time, and earning enough?consistently to do so. ?Doing so as an amateur managing a retirement portfolio is a particularly hard version of this problem. ?Let me point out some of the areas where it will be hard:

1) The retiree doesn?t know how long he, his spouse, and anyone else relying on him will live. ?Averages can be calculated, but particularly with two people, the odds are that at least one will outlive an average life expectancy. ?Can they be conservative enough in their withdrawals that they won?t outlive their assets?

It?s tempting to overspend, and the temptation will get greater when bad events happen that break the budget, whether those are healthcare or other needs. ?It is incredibly difficult to?avoid paying for an immediate pressing need, when the soft cost?is harming your future. ?There is every incentive to say, ?We?ll figure it out later.? ?The odds on that being true will be low.

2) One conservative estimate of what the safe withdrawal rate is on a perpetuity is the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note plus around 1%. ?That additional 1% can be higher after the market has gone through a bear market, and valuations are cheap, and as low as zero near the end of a bull market.

That said, most?people people with discipline want a simple spending rule, and so those that are moderately conservative choose that they can spend 4%/year of their assets. ?At present, if interest rates don?t go lower still, that will likely (60-80% likelihood) work. ?But if income needs are greater than that, the odds of obtaining those yields over the long haul go down dramatically.

3) How does a retiree deal with bear markets, particularly ones that occur early in retirement? ?Can?he and?will he reduce his expenses to reflect the losses? ?On the other side, during bull markets, will he build up a buffer, and not get incautious during seemingly good times?

This is an easy prediction to make, but after the next bear market, look for a scad of ?Our retirement is ruined articles.? ?Look for there to be hearings in Congress that don?t amount to much ? and if they?do amount to much, watch them make things worse by?creating R Bonds, or some similarly bad idea.

Academic risk models typically used by financial planners typically don?t do path-dependent analyses.? The odds of a ruinous situation is far higher than most models estimate because of the need for withdrawals and the autocorrelated nature of returns ? good returns begets good, and bad returns beget bad in the intermediate term.? The odds of at least one large bad streak of returns on risky assets during retirement is high, and few retirees will build up a buffer of slack assets to prepare for that.

4)?Retirees should avoid investing in too many income vehicles; the easiest temptation to give into is to stretch for yield ? it?is the oldest scam in the books. ?This applies to dividend paying common stocks, and stock-like investments like REITs, MLPs, BDCs, etc. ?They have no guaranteed return of principal. ?On the plus side, they may give capital gains if bought at the right time, when they are out of favor, and reducing exposure when everyone is buying them.? Negatively, all junior debt tends to return worse on average than senior debts.? It is the same for equity-like investments used for income investing.

Another easy prediction to make is that junk bonds and non-bond income vehicles will be a large contributor to the shortfall in asset return in the next bear market, because many people are buying them as if they are magic. ?The naive buyers think: all they do is provide a higher income, and there is no increased risk of capital loss.

5) Leaving retirement behind for a moment, consider the asset accumulation process.? Compounding is trickier than it may seem. ?Assets must be selected that will grow their value including dividend payments over a reasonable time horizon, corresponding to a market cycle or so (4-8 years). ?Growth in value should be in excess of that from expanding stock market multiples or falling interest rates, because you want to compound in the future, and low interest rates and high stock market multiples imply that future compounding opportunities are lower.

Thus, in one sense, there is no benefit much from a general rise in values from the stock or bond markets. ?The value of a portfolio may have risen, but at the cost of lower future opportunities. ?This is more ironclad in the bond market, where the cash flow streams are fixed. ?With stocks and other risky investments, there may be some ways to do better.

Retirees should be aware that the actions taken by one member of a large cohort of retirees will be taken by many of them.? This makes risk control more difficult, because many of the assets and services that one would like to buy get bid up because they are scarce.? Often it may be that those that act earliest will do best, and those arriving last will do worst, but that is common to investing in many circumstances.? As Buffett has said, ?What a?wise man?does in the beginning a?fool?does in the?end.?

6) Retirement investors should avoid taking too much?or too little risk. It?s psychologically difficult to buy risk assets when things seem horrible, or sell when everyone else is carefree. ?If a person can do that successfully, he is rare.

What is achievable by many is to maintain a constant risk posture. ?Don?t panic; don?t get greedy ? stick to a moderate asset allocation through the cycles of the markets.

7) With asset allocation, retirees should overweight out-of-favor asset classes that offer above average cashflow yields. ?Estimates on these can be found at GMO or?Research Affiliates. ?They should rebalance into new asset classes when they become cheap.

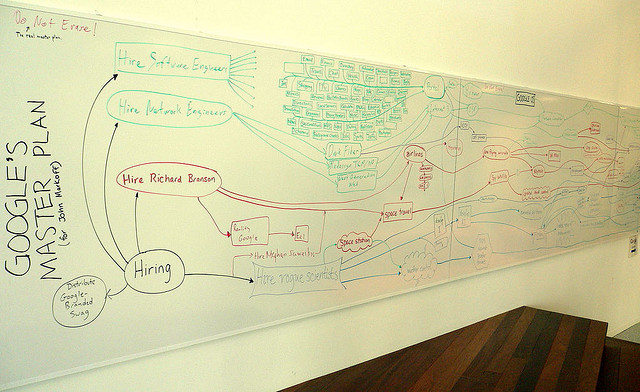

Another way retirees can succeed would be investing in growth at a reasonable price ? stocks that offer capital growth opportunities at an inexpensive price and a margin of safety. ?These companies or assets need to have large opportunities in front of them that they can reinvest their free cash flow into. ?This is harder to do than it looks. ?More companies look promising and do not perform well than those that do perform well.

Yet another way to enhance returns is value investing: find undervalued companies with a margin of safety that have potential to recover when conditions normalize, or find companies that can convert their resources to a better use that have the willingness to do that. ?After the companies do well, reinvest in new possibilities that have better appreciation potential.

8 ) Many say that the first rule of markets is to avoid losses. ?Here are some methods to remember:

- Always seek a margin of safety. ?Look for valuable assets well in excess of debts, governed by the rule of law, and purchased at a bargain price.

- For assets that have fallen in price, don?t try to time the bottom ? buy the asset when it rises above its 200-day moving average. This can limit risk, potentially buying when the worst is truly past.

- Conservative investors avoid the areas where the hot money is buying and own assets being acquired by patient investors.

9) As assets shrink, what should be liquidated? ?Asset allocation is more difficult than it is described in the textbooks, or in the syllabuses for the CFA Institute or for CFPs.? It is a blend of two things ? when does the investor need the money, and what asset classes offer decent risk adjusted returns looking forward?? The best strategy is forward-looking, and liquidates what has the lowest risk-adjusted future return. ?What is easy is selling assets off from everything proportionally, taking account of tax issues where needed.

Here?s another strategy that?s gotten a little attention lately: stocks are longer assets than bonds, so use bonds to pay for your spending in the early years of your retirement, and initially don?t sell the stocks.? Once the bonds run out, then start selling stocks if the dividend income isn?t enough to live on.

This idea is weak.? If a person followed this in 1997 with a 10-year horizon, their stocks would be worth less in 2008-9, even if they rocket back out to 2014.

Remember again:

You don?t benefit much from a general rise in values from the stock or bond markets. ?The value of your portfolio may have risen, but at the cost of lower future opportunities.

That goes double in the distribution phase. The objective is to convert assets into a stream of income. ?If interest rates are low, as they are now, safe income will be low. ?The same applies to stocks (and things like them) trading at high multiples regardless of what dividends they pay.

Don?t look at current income. ?Look instead at the underlying economics of the business, and how it grows value. ?It is far better to have a growing income stream than a high income stream with low growth potential.

Deciding what to sell is an exercise in asset-liability management.? Keep the assets that offer the best return over the period that they are there to fund future expenses.

10) Will Social Security take a hit out around 2026? ?One interpretation of the law says that once the trust fund gets down to one year?s worth of?payments, future payments may get reduced to the level?sustainable by expected future contributions, which is 73% of expected levels. ?Expect a political firestorm if this becomes a live issue, say for the 2024 Presidential election. ?There will be a bloc of voters to oppose leaving benefits unchanged by increasing Social Security taxes.

Even if benefits last at projected levels longer than 2026, the risk remains that there will be some compromise in the future that might reduce benefits because taxes will not be raised.? This is not as secure as a government bond.

11) Be wary of inflation, but don?t overdo it. ?The retirement of so many people may be deflationary ? after all, look at Japan and Europe so far. ?Economies also work better when there is net growth in the number of workers. ?It will be tempting for policymakers to shrink what liabilities they can shrink through inflation, but there will also be a bloc of voters to oppose that.

Also consider other risks, and how assets may fare. ?Retirees should analyze what exposure they have to:

- Deflation and a credit crisis

- Expropriation

- Regulatory change

- Trade wars

- Changes in taxes

- Asset illiquidity

- Reductions in reimbursement from government programs like Medicare, Medicaid, etc.

- And more?

12) Retirees need a defender of two against slick guys who will try to cheat them when they are older. ?Those who have assets are a prime target for scams. ?Most of these come dressed in suits: brokers and other investment salesmen with plausible ways to make assets stretch further. ?But there are other scams as well ? retirees should run everything significant past a smart younger person who is skeptical, and knows how to say no when it is necessary.

Conclusion

Some will think this is unduly dour, but this?is realistic. ?There are not enough resources to give all of the Baby Boomers a lush retirement, without unduly harming younger age cohorts, and this is true over most of the developed world, not just the US.

Even with skilled advisers helping, retirees need to be ready for the hard choices that will come up. They should think through them earlier rather than later, and take some actions that will lower future risks.

The basic idea of retirement investing is how to convert present excess income into a robust income stream in retirement. ?Managing a pile of assets for income to live off of is a challenge, and one that most people?are not geared up for, because poor planning and emotional decisions lead to subpar results.

Retirees should?aim for the best future investment opportunities with a margin of safety, and let the retirement income take care of itself. ?After all, they can?t rely on the markets or the policymakers to make income opportunities easy.