This was published in late 2007 at RealMoney. ?I don’t know exactly when.

=-=-=-=-=-=-===-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=-==-=-===-==-=-=-=====–==-=-=-

I came into the investment business through the back door as an actuary and a risk manager. For more than a decade, I worked inside several large life insurance companies creating investment products. My team?s dirty secret? We just wanted to clip a smallish profit on the assets, without taking much risk ourselves. If we could do that, and produce a reliable investment result for our clients, we were happy.

That was my job then; in a different sense, it is my job now.? My goal as a writer, commentator, and independent money manager is to take much of the risk out of personal investing while retaining most of the profit potential.

Nobody can avoid every up and down in the market. What you can do, however, is to ensure that you don?t get crushed when the market rolls over. My own portfolio is a case in point. Over the last seven years, starting in September of 2000, my investment process has yielded an annualized return of 20% a year.? I manage to a long horizon, so I don?t try to cut losses in the short run.? I am willing to take pain if I feel that the underlying fundamentals are intact.? I had only one losing year in that time, but it was a doozy. During four months in 2002, my portfolio lost 32% of its value.? I was shaken, but I scraped together my spare cash and invested. Over the next 16 months, my portfolio rallied 86%, which I found about as astounding as the 32% loss.?

The experience taught me that risk control works. Oddly enough, though, risk control doesn?t get a lot of attention. The most popular books and websites on investing spend nearly all their time focusing on the prospect of big returns; they rush over the matter of how to avoid big losses or how to deal with these losses when they happen. The result? Many people sour on investing because they take risks they don?t intend and lose a lot of money. They conclude that the investment game is rigged against them and they leave investing.

It doesn?t have to be that way. Let me suggest five simple ways you can control your worst tendencies, reduce your risk and become a happier investor.

Spread your bets around. The most basic rule of risk control is to diversify your investments. It is also the most neglected rule.

Perhaps the neglect is because most people don?t understand what diversification means. For starters, it means building a buffer against all the stuff you would prefer not to think about?unemployment, sickness, a horrible bear market, etc. Before you start investing, you need three to six months of living expenses set aside in bank deposits, money market funds and short-term bond funds. Having this cushion protects you from having to sell investments in an emergency, which in turn allows you to take risk with your remaining assets.

On top of your emergency funds, your portfolio should include a dollop of high quality bonds that mature in anywhere from two to 10 years. For older people, bonds cushion the downside of the total portfolio and ensure that you can?t be devastated by a stock market downturn. For younger people, bonds provide an additional benefit?you can sell them to buy stocks or other investments if the market plunges and you spot tempting bargains. So how much of your portfolio should you devote to bonds? As little as 20% of your portfolio if you?re in your twenties and a risk taker; 50% or more if you?re above 65 or naturally cautious.

Once you?ve got your emergency funds and your bonds stowed away, it?s time for stocks?and, once again, diversification should be your starting point. You don?t want to bet your entire future on a handful of stocks or on one industry or even on a single country. The easiest way to ensure that you?re widely diversified among many different stocks is to invest in a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund that holds scores of individual stocks, representing a multitude of different industries.

If, like me, you prefer to buy individual stocks, you have to balance your desire to be widely diversified against how much money you have to invest and?just as important?how much time you have to spend researching companies. My minimum for reasonable diversification is 15 stocks. When I started investing as a serious amateur back in 1992, I started with 15 stocks in my portfolio, and I bought $2,000 of each of them. Since then I?ve made maybe a dozen serious investing mistakes, but because I had my money diversified among many companies, none of my mistakes ever cost me more than 2% of my total capital.

These days I?m even more diversified: I run with 35 stocks, which is close to the maximum an individual can hope to track and research. Generally I devote an equal amount of money to each of my stocks?an equal weight, in investment jargon?because usually I can?t tell what my best ideas are. When a position gets more than 20% away from its target weight, I consider whether I should bring it back to equal weight or sell the whole thing.? Occasionally I deviate from equal weighting, but only when I have a very safe stock that is grossly undervalued. I never go above a double weight, which means that a single stock rarely accounts for even 6% of my overall portfolio.

The final way I diversify my portfolio is intellectually. I try to listen to as many viewpoints from as many different people as I can. I do this because the ideas of all but the most careful investors are internally correlated. They reflect some idea of what the economy is likely to do in the future, and they lean toward companies that fit that view. Some investors love companies with high P/E multiples and incredible growth stories. Other investors?and I?m one of them?love companies in distressed industries that are going for a song. You should listen to both camps. Doing so insures that you learn to think about investments from a wide number of perspectives. It makes investing more businesslike.

Here?s one trick you might find handy. As I gather my ideas from a wide number of sources, I print them out, and place them in a pile next to my computer.? I try to forget who gave me the idea, which forces me to look at the idea fresh, without the biases that come from trusting an authority figure.

Follow the cash. Most investors pay a lot of attention to how much a company earns; few investors realize how easily management can manipulate those earnings with fancy accounting. To reduce risk in the stocks you buy, keep an eye on a company?s cash flow as well as its earnings.

Your first step should be to look with a questioning eye at the non-cash, or accrual items, on the company?s financial statements. These include entries for such things as depreciation, inventory adjustments, or bad debt allowances. Cash is certain, but non-cash items such as these are anything but. Earnings can be thrown up or down by how quickly management decides to write down the value of a new factory or by how much it estimates its inventory of rotary-dial phones is really worth. The accounting industry tries to set guidelines for accruals, but management still has a lot of leeway.

For non-accountants, the easiest way to sniff out possible trouble is to compare the earnings statement with the cash flow statement?specifically the top segment of the cash flow statement, which shows ?cash flow from operations.? This is the amount of cold hard cash the company?s operations are generating, before making any payouts to lenders or shareholders, or investing in new equipment. In most cases, if a company?s earnings are growing, its cash flow from operations should also be going up, since higher earnings just about always mean more cash going through the business. So what if a company says its earnings are growing, but its cash flow isn?t?? You should be very, very wary. The financial statements aren?t necessarily bogus, but you have to puzzle out how a company?s earnings can be rising without throwing off more cash.

Sometimes there is no good answer to this puzzle. Remember Sunbeam, the small-appliance maker that hired ?Chainsaw Al? Dunlap to goose its business? I owned the stock in 1996 when Dunlap came on the scene. But after two earnings reports I became suspicious. ?All of these restructuring efforts are improving earnings, but they?re not producing cash from operations,? I thought. ?What gives?? I concluded something fishy was going on, so I sold for a nice gain. Over the next six months, the stock rose by 60%?then plunged 90% as it became clear that most of Sunbeam?s increase in earnings was the result of accounting shenanigans, not real business gains.

Love the unloved. Most people avoid industries that are under stress.? Who can blame them?? The industry outlook is horrible; there can?t be anything good here.?

I take a different view. I believe that some of the safest plays you can make consist of buying financially strong names in weak sectors. These companies are usually cheap in comparison to their earnings and to their book values. You can find out more about how to spot undervalued companies by visiting the website of Tweedy Browne, the famous value-investing firm, and reading their excellent paper on What Has Worked In Investing (http://www.tweedy.com/library_docs/papers/what_has_worked_all.pdf).

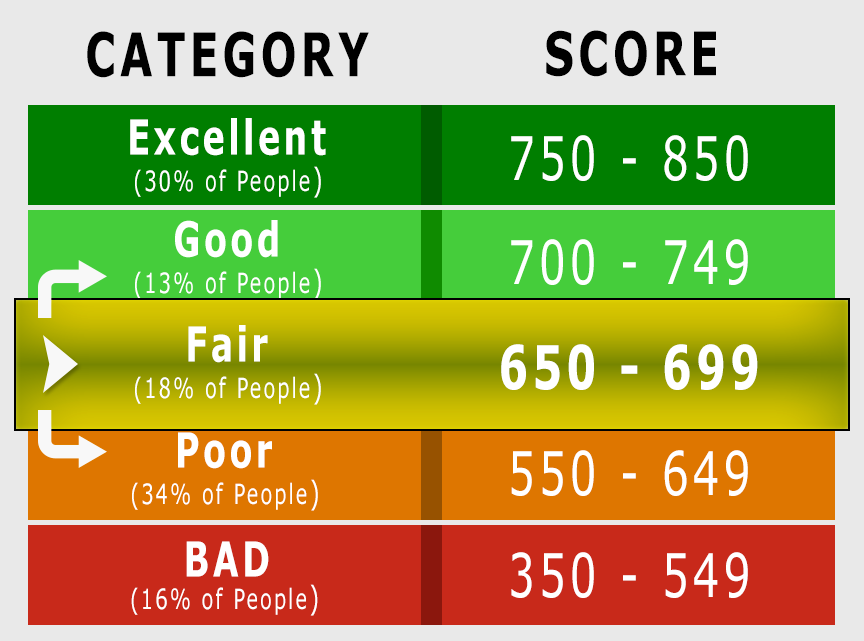

In addition to the standard measures, I look for companies with good bond ratings.? The ratings agencies are out of favor now, because of the current furor over securitization, but they produce the best single measure of a company?s creditworthiness. The raters award the best ratings to companies that can generate cash well in excess of what is needed to pay all their creditors and that possess a low ratio of debt to assets.

Once I?ve bought a stock, I try to be patient, because the payoff is usually not instantaneous. In 2001, when steel stocks looked horrible, I bought Nucor, the soundest company in the industry. Steel companies dropped like flies in 2002 and the stock did nothing?until the end of the year, when enough steel-making capacity had been closed down that steel prices began to rise. Nucor flew, and I made a nice profit.

The key to making this contrarian strategy work is to not overdo it. Some industries?newspapers, say, or fixed-line telecom companies?truly do have questionable futures. You have to analyze each situation on its own merits.? At present, my favorite industries are insurance, energy, agriculture/food processing, cement, and chemicals.

My value-hunting approach means that most of the stuff I buy is not popular. I veer away from firms that are pioneering new technologies or markets. Such companies are easy to get enthusiastic about, but difficult to value because there are so many unknowns.

When I talk about the companies I own, the response is often, ?You invest in obscure stuff.? What do you think about Google?? I don?t have an opinion on Google.? I can?t tell you whether it will produce enough profits over the years to justify its current price or not.? So much depends on future tastes and competition. I?d rather own cement companies; they are very difficult to make obsolete.

Take emotion out of it You should look over your portfolio two to four times a year. In my own case, I follow a very structured process. I take all of the investment ideas that I have gathered up since my last portfolio pruning, and rate them on valuation, momentum, and accounting quality to arrive at a composite measure of their overall desirability. I compare these ideas to the companies that are already in my portfolio.

This sounds complicated and so it is. But exactly how you do your ranking is less important than having a system for comparing the stocks in your existing portfolio to the alternatives that the market is offering you. Your goal should to take some of the emotion out of investing. You don?t want to fall in love with the companies that you already own. To avoid this, I try to pinpoint what companies in my ideas list are better than the median idea in my portfolio.? These become purchase candidates and I do further research on them.

I also look at the companies in my portfolio that are below the median in desirability, and I ask why I?m keeping them. In many cases, the companies are less desirable because they?ve gone up in price and are no longer as cheap as the once were. In other cases, they?re less desirable for the opposite reason? the company?s business has deteriorated and shows no signs of turning around. Every three to four months, I typically sell two or three companies from my 35-stock list and replace them with more promising companies from the ideas list. I typically hold a stock for three years.? Many of my ideas go against me at first, but often turn and make money for me later.

Smart money is slow money. If a stockbroker or financial planner tells you that you?ll miss a huge opportunity if you don?t buy right now, ignore them. A smart investor moves at his or her own pace.

To make sure that you don?t get pressured into buying something, it?s nearly always a good rule to avoid salespeople. Stockbrokers, financial planners, mutual fund salespeople and even the experts on the television all have financial incentives that can pull them in directions opposite to what?s in your best interest. Before buying any stock or any financial product, you should do a bit of background reading so that you understand what you?re buying and how much rival products cost. In many cases?insurance is a good example?you?ll find that the simplest product is your best buy. Complexity in insurance, and many other investments, is usually a cover for increased fees.

Especially when it comes to buying stocks, patience is your best friend. If an idea seems like a sure thing, sit on it for a month.? If the idea is still a good one, you will usually still have time to act on it.? If the idea is a bad one, the extra time will help you do further research and may make its problems evident.

One of the best ways to make money is to avoid losing it. When I approach new ideas, I try to ask how likely it is that I will lose money, and how much I could lose if I am wrong. I lose about 20% of the time. Six times in the last 15 years, I have lost half my money on an investment. Those are actually pretty good numbers. I can?t avoid all losses, but if I wait, take my time and do my research, I can limit my losses, and make money on the rest of my ideas.