I’m thinking of starting a limited series called “dirty secrets” of finance and investing. ?If anyone wants to toss me some ideas you can contact me here. ?I know that since starting this blog, I have used the phrase “dirty secret” at least ten times.

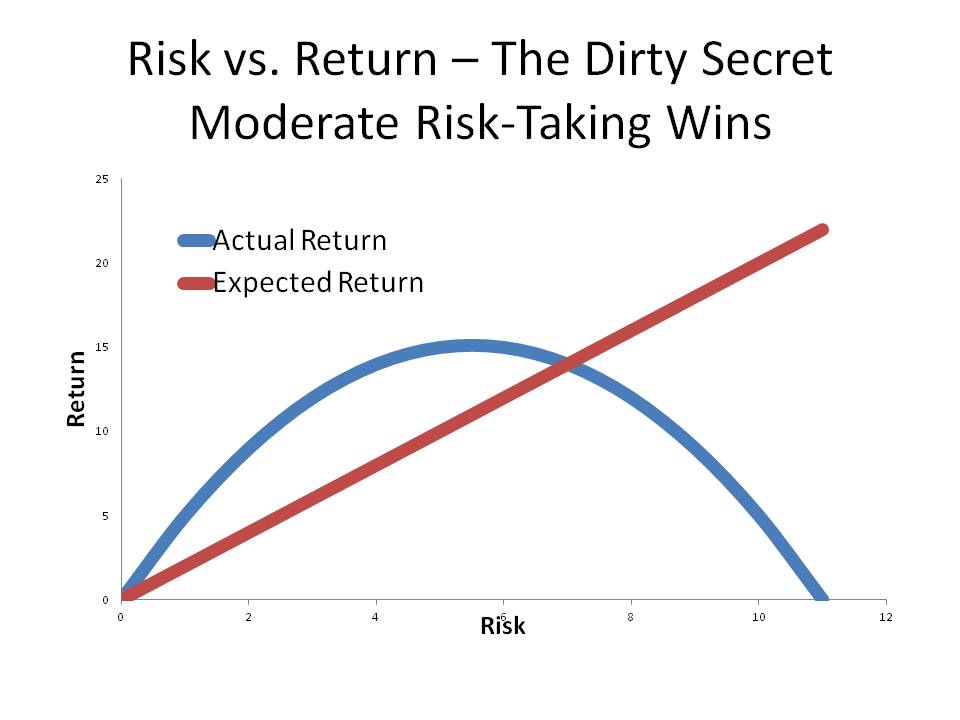

Tonight’s dirty secret is a simple one, and it derives mostly from investor behavior. ?You don’t always get more return on average if you take more risk. ?The amount of added return declines with each unit of additional risk, and eventually turns negative at high levels of risk. ?The graph above is a vague approximate representation of how this process works.

Why is this so? ?Two related reasons:

- People are not very good at estimating the probability of success for ventures, and it gets worse as the probability of success gets lower. ?People overpay for chancy lottery ticket-like investments, because they would like to strike it rich. ?This malady affect men more than women, on average.

- People get to investment ideas late. ?They buy closer to tops than bottoms, and they sell closer to bottoms than tops. ?As a result, the more volatile the investment, the more money they lose in their buying and selling. ?This malady also affects men more than women, on average.

Put another way, this is choosing your investments based on your circle of competence, such that your probability of choosing a good investment goes up, and second, having the fortitude to hold a good investment through good and bad times. ?From my series on dollar-weighted returns you know that the more volatile the investment is, the more average people lose in their buying and selling of the investment, versus being a buy-and-hold investor.

Since stocks are a long duration investment, don’t buy them unless you are going to hold them long enough for your thesis to work out. ?Things don’t always go right in the short run, even with good ideas. ?(And occasionally, things go right in the short run with bad ideas.)

For more on this topic, you can look at my creative piece,?Volatility Analogy. ?It explains the intuition behind how volatility affects the results that investors receive as they get greedy, panic, and hold on for dear life.

In closing, the dirty secret is this: size your risk level to what you can live with without getting greedy or panicking. ?You will do better than other investors who get tempted to make rash moves, and act on that temptation. ?On average, the world belongs to moderate risk-takers.

Great topic – I’ve always found it advantageous to employ many moderate risk strategies to build wealth. Sure, if you had 20 lucrative opportunities with odds of success at 10% each, then spread your bets and roll the die. However, such opportunities are not so common, while modest opportunities are a dime a dozen, and yet tend to get ignored by a lot of people. The big three start with investing in yourself – college etc. Then saving/investing. Finally, house and car purchases and related financing. After that, it’s how you distribute your resources, with flexibility the key. It would have been almost impossible for us to invest in a business opportunity if we hadn’t been thinking ahead, and I now expect the IRR on that investment to exceed 30%.

I’ve run into this with friends who’re being sold (typically MLM) business ‘opportunities’. They’re very excited by these, but much less interested in more routine things they could do around debt, prepaying insurance premiums, etc in their life – many of which yield tax-equivalent IRR north of 20%.

I like the topic, but a big question is how does one define risk?

I’d say, not having enough money when you need it. This results from either permanent loss of capital or loss of purchasing power over time.

This is very similar to the diminishing returns argument- an under-appreciated economic concept. In this case you don’t just plateau at the high end (of risk), you actually “go negative” (return goes negative vs. increasing risk).

Survivorship bias also plays into it. People know about the fabulous successes, such as Steve Jobs. I don’t think most people would really like to have Steve Jobs’ “investment” experience, except at the end. He almost bankrupted several entities, including himself, several times. Most of his competitors did bankrupt themselves, but Apple survived, so everybody points to it as a good case study. I wouldn’t advise anybody to use Apple as a model for success- too risky. Apple is as rare as the proverbial black swan- but in the positive way.

Excellent post.

Can’t get the “you can contact me here” link to work.

What I have found useful is the idea that there are (to a first order) only a small number of “things” that one can invest in. Everything else is built out of a combination of them.

– cash

– bonds

– businesses/equities

– property (could try to generalise this, but generally based on the audience, it has been easier to accept this as its own category)

– lumps of stuff (i.e. commodities, art, etc)

This helps to remove some of the “magic” from obscure financial products and outlandish returns.

I’d go even further than that and say that everything is either a risky asset (equities, real estate, commodities, corporate bonds) or a riskless asset (sovereign bonds/cash). In other words everything is either a stock or a sovereign bond. Risk in this context being volatility.