Classic: Using Investment Advice, Part 4 [Tread Warily on Media Stock Tips]

The following was published at RealMoney on 9/26/05.? I have augmented it at the bottom, so if you’ve read it before, at the bottom, there is more.

-=-===-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Often investors, both professional and amateur, will run across what seems like a great investment idea in the media and run to act on it. My advice is simple: Wait. For months, perhaps.

I’ll lay out my approach to media touts, as well as a list of current stock tips, later on. But first, let’s see how the market reacts to them.

Say that the idea is to go long on a stock. At the market open after the story appears, a rush of orders will push the stock’s price higher. Then, as the day progresses, the stock will drop and end the day lower than at the open, but usually higher than the prior close.

For the first few days, the market responds to the supply/demand imbalance, and then the merits of the investment become clear. As Benjamin Graham observed, in the short run, the market is a voting machine; in the long run, it’s a weighing machine.

My experience has been that after the initial supply/demand imbalance period, the performance of media-touted investments is market-like on average, leaving the early buyers with assets that generally underperform.

The degree of underperformance varies with the size and character of the audience that saw the story. In general, the larger the audience, the larger the reaction.

The reaction also tends to be larger the lower the experience level of the audience (as long as there is some investment experience — people with no experience won’t do anything). Novice investors are the ones that jump at ideas that seem to be hot when under the media spotlight. Experienced investors tend to have their own idea-generation processes; they either ignore the idea or throw it into their process for later review.

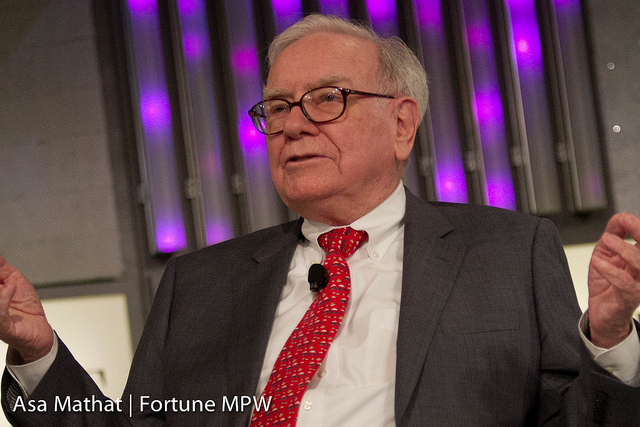

Naturally, the bigger the media play, the bigger the splash. A front-page article makes waves; a tidbit mentioned in passing should have no impact, even though it might be powerful information in the hands of an informed investor. The impact is also greater depending on the fame, or perceived skill, of the source.

The potential size of the investment is negatively related to the degree of underperformance. A positive article on General Electric will have less impact on the price of GE than a similarly positive article on a smaller company. Naive investors place their market buy orders without thinking through the degree of liquidity of the investment.

Know Your Enemies

A number of media sources are particularly given to sensationalism, such as newsletters, online message boards, radio and sometimes television. The risk is particularly great when the “expert” speaking has an ill-defined financial interest in the idea under discussion.

The higher the level of emotion employed, the lower the level of humility, and the less the focus on what could go wrong, the more you should be skeptical. The adviser can sometimes be an enemy of wealth creation.

There are other enemies as well: sophisticated traders who watch for unusual trading activity off of media play and take a short-term contrary position. They short into bullish news and buy bearish news when they perceive that the money acting quickly on it is naive.

What to Do

My advice is simple: Wait. Invest in a subset of the ideas that still have value and have not fully reacted to the information after a period of time.

Also, compare new ideas as a group vs. each other and against the existing assets in your portfolio. Only add a new idea if you think it will beat the median idea in your portfolio. I have detailed these ideas in a piece titled “Become a Smarter Seller.” [DM in 2013: wish I had a link, it was a great piece.] I usually wait one to three months after I get an externally generated idea before I consider acting on it. I rank new ideas against my current portfolio and choose new ideas based on a mosaic of different factors — mainly cheapness, momentum (or anti-momentum) and industry exposure. I consider selling positions more expensive than the current median idea in my portfolio, and buying ideas that are cheaper than the current median. The following decision/reaction grid helps explain my actions:

| Decision/Reaction Grid | Merit of the idea still good? | Merit of the idea bad? |

| Results have already occurred. | Can’t kiss them all. | Glad I missed that bad boy. |

| Results have not occurred yet. | Invest. | Don?t invest. |

There is a cost to waiting: Some ideas get away from you. This is called implementation shortfall by some. I say you can’t kiss them all.

However, waiting has the positive effect that with the passage of time, some investment proposals are proved wrong. Missing wrong ideas is a real benefit for any investment program. ?Also, waiting takes some of the emotion out of the decision-making process, which helps to avoid errors.

After the waiting period, I ask whether the underlying investment thesis is still valid and whether that is reflected in the current stock price. The media piece that generated the initial interest is long since forgotten, so the emotion and excess stock price moves are gone. But the value might still be there, and with enough new investment ideas, some of them will present real opportunities for above-average investment returns.

Back to 2013

In 2005, I closed the piece with a list of stocks that were interesting, but that I did not own at present.? Look for my next ?Industry Ranks? piece in late April or early May.? You will get some ideas there.

One more thing to confess, I wrote this series with Cramer in mind, but not only Cramer.? I cringe when I hear people speaking or writing about specific investments with a high degree of certainty.

Investing is not certain, even for those of us who try to invest with a margin of safety.? The proper sense of investing engenders sobriety and caution.? That is the opposite of what sells newsletters, gets listeners on the radio, and viewers on television.

I?ve been invited onto TV three times more than I have been on TV.? In talking with a producer, I will explain the issues involved, and I will tell him they are complex.? This doesn?t make for good soundbites.? The producer either concludes there is no easy story here, or seeks out someone who will make the show snappy.

I leave you with this simple concept: if it is entertaining, it is probably not useful for investing.? (And as an aside, that is why you will not see a word related to entertain in my disclaimer.? I am offering opinions, not advice.)? Truly that?s all anyone in the markets can do, but because so many people dupe the credulous, of which there is one born every minute, that?s why we have extensive regulations for disclosure and advertising.

Be skeptical. Research, and be a buyer.? Do not let yourself be sold to.

Finally, avoid emotive media regarding investing.? Listen to those who write dispassionately or better, learn, and do your own research.

![Classic: Using Investment Advice, Part 4 [Tread Warily on Media Stock Tips]](https://alephblog.com/wp-content/themes/overlay/images/blog-img-3-2.png)