What Caused the Financial Crisis?

Photo Credit: Alane Golden || Sad but true — the crisis was all about bad monetary policy, a housing bubble, and poor bank risk management======================

There are a lot of opinions being trotted around ten years after the financial crisis.? A lot of them are self-serving, to deflect blame from areas that they want to protect.? What you are going to read here are my opinions.? You can fault me for this: I will defend my opinions here, which haven?t changed much since the financial crisis.? That said, I will simplify my opinions down to a few categories to make it simpler to remember, because there were a LOT of causes for the crisis.

Thus, here are the causes:

1) The Federal Reserve and the People?s Bank of China

For different reasons, these two central banks kept interest rates too low, touching off a boom in risk assets in the USA.? The Fed kept interest rates too low for too long 2001-2004. The Fed explicitly wanted to juice the economy via the housing sector after the dot-com bust, and the withdrawal of liquidity post-Y2K.? Also, the slow, predictable way that they tightened rates did little to end speculation, because long rates did not rise, and in some cases even fell.

The Chinese Central Bank had a different agenda.? It wanted to keep the Yuan cheap to continue growing via exporting to the US.? In order to do that, it needed to buy US assets, typically US Treasuries, which balanced the books ? trading US bonds for Chinese goods ? and kept longer US interest rates lower.

Both of these supported the:

2) Housing Bubble

This is the place where there are many culprits.? You needed lower mortgage underwriting standards. This happened through many routes:

- US policy pushing home ownership at all costs, including tax-deductibility of mortgage interest.

- GSEs guaranteeing increasingly marginal loans, and buying lower-rated tranches of subprime RMBS. They ran on such a thin capital base that it was astounding.? Don?t forget the FHLBs as well.

- Politicians and regulators refused to rein in banks when they had the power and tools to do so.

- Securitization of private loans separated origination from risk-bearing, allowing underwriting standards to deteriorate. Volume was rewarded, not quality.

- Mortgage insurers and home equity loans allow people to borrow a far greater percentage of the value of the home than before, for conforming loans.

- Appraisers went along with the game, as did regulators, which could have stopped the banks from lowering credit standards. Part of the fault for the regulatory mess was due to the Bush Administration downplaying financial regulation.

- The Rating Agencies gave far too favorable ratings to untried asset classes, like ABS and private RMBS securitizations. This is for two reasons: financial regulators required that the companies they oversaw must use ratings for assessing capital needed to cover credit risk, and did not rule out asset classes that were unproven, as prior regulators had done.? Second, CDOs and similar structures needed the assets they bought to have ratings for the same reason.

- There was a bid for yieldy assets on the part of US Hedge funds and foreign financial firms. Without the yield hogs who bid for CDO paper, and other yieldy assets, the bubble would not have grown so big.

- Financial guarantors insured mortgage paper without having good models to understand the real risk.

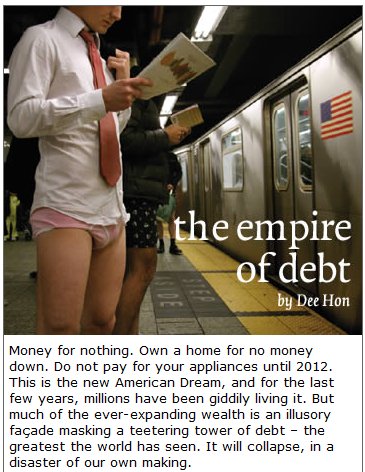

- People were stupid enough to borrow too much, assuming that somehow they would be able to handle it.? As with most bubbles, there were stupid writers pushing the idea that investing in housing was “free money.”

3) Bank Asset-liability management [ALM] for large commercial and investment banks was deeply flawed. ?It resulted in liquid liabilities funding illiquid assets.? The difference in liquidity was twofold: duration and credit.? As for duration, the assets purchased were longer than the bank?s funding structures.? Some of that was hidden in repo transactions, where long assets were financed overnight, and it was counted as a short-term asset, rather than a short-term loan collateralized by a long-term asset.

Also, portfolio margining was another weak spot, because as derivative positions moved against the banks, some banks did not have enough free assets to cover the demands for security on the loans extended.

As for credit, many of the assets were not easily saleable, because of the degree of research needed to understand them.? They may have possessed investment grade credit ratings, but that was not enough; it was impossible to tell if they were ?money good.?? Would the principal and interest eventually be paid in full?

The regulatory standards let the banks take too much credit risk, and ignored the possibility that short-term lending, like repos and portfolio margining could lead to a ?run on the bank.?

4) Accounting standards were not adequate to show the risks of repo lending, securitizations, or derivatives.? Auditors signed off on statements that they did not understand.

===============

That?s all, I wanted to keep this simple.? I do want to say that Money Market Funds were not a major cause of the crisis.? The reaction to the failure of Reserve Primary was overdone.? Because of how short the loans in money market funds are, the losses from money market funds as a whole would have been less than two cents on the dollar, and probably a lot smaller.

Also, bailing out the banks sent the wrong message, which will lead to more risk later.? No bailouts were needed.? Deposits were protected, and there is no reason to protect bank stock or bondholders.? As it was, the bailouts were the worst possible, protecting the assets of the rich, while not protecting the poor, who still needed to pay on their loans.? Better that the bailouts should have gone to reduce the principal of loans of those less-well-off, rather than protect the rich.? It is no surprise that we have the politics? we have today as a result.? Fairness is more important than aggregate prosperity.

PS — the worst of all worlds is where the government regulates and gives you the illusion of protecting you when it does not protect you much at all.? That tricks people into taking risks that they should not take, and leaves individuals to hold the bag when bad economic and regulatory policies fail.