Picture Credit: All pictures today are by me. Aleph Blog

What sounded simple yesterday proved harder to put into a spreadsheet than I expected. Nonetheless, I got it done. As an aside, I wanted to mention one thing I don’t think I have disclosed before: I competed in the Modeloff competition four or five times. I always got to the second round. One time my first round score had me in the top 20, and one time my second round score had me in the top 1%. I never made it to the finals — it is no place for old men. I asked one of the organizers if I was the oldest guy in the contest, and he said, “No, there is one guy older than you.”

The grand challenge of this model was solving two messy simultaneous equations to find the loss percentage. That took me two hours to solve, due to repeated errors where I tried to do it too quickly. Always go back to first principles, and solve things step by step.

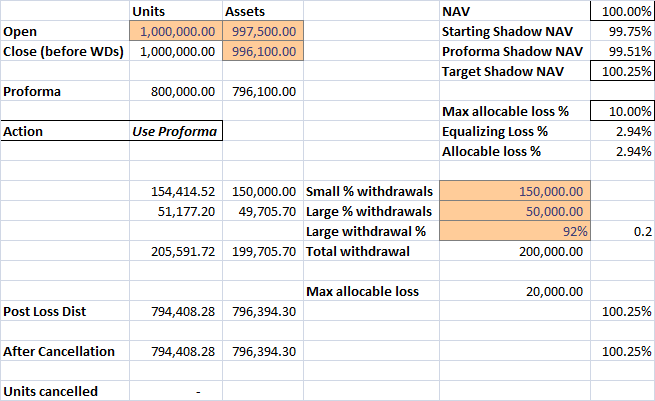

Tonight, I am only changing one variable, the most important one for this discussion, what are the assets worth at the close, prior to withdrawals. In my first example, that value is $996,100, leaving the Closing Pro-forma Shadow NAV at 99.51%, which doesn’t break the buck by a hair. The withdrawals get paid in full, and the fund lives to fight for another day with no press release.

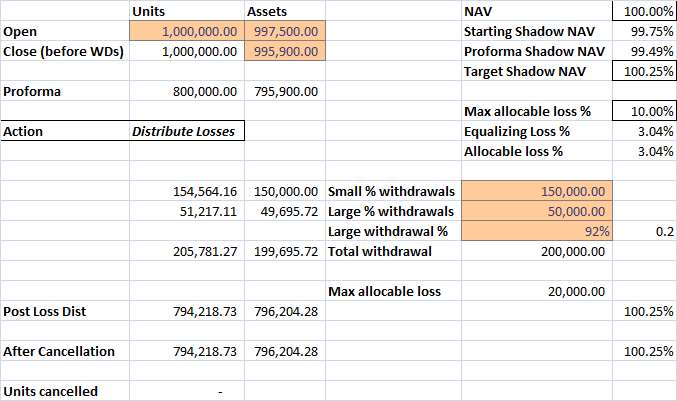

In the second scenario, the closing assets prior to withdrawal are $995,900, leaving the Closing Pro-forma Shadow NAV at 99.49%, which breaks the buck by a hair. The withdrawals get paid at a 3.04% discount. The small withdrawers lose additional units, but the amount of money they requested comes in full. The large withdrawers don’t get paid in full. A large withdrawer is asking for all or almost all of their money back. The assumption in this set of scenarios is that the large withdrawers are asking for 92% of their assets back in aggregate. The calculation balances the losses between a payment discount, and loss of most of the remaining units.

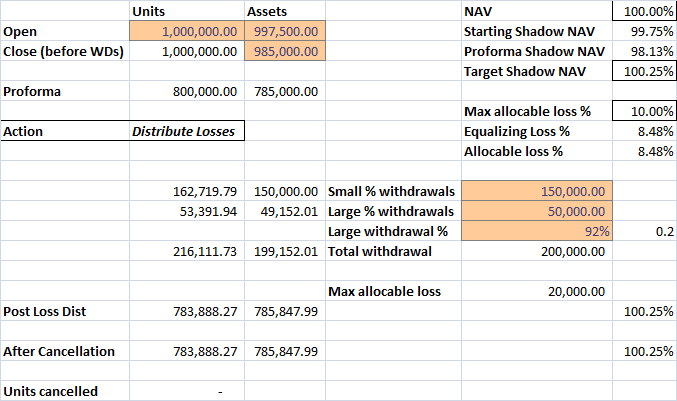

In the third scenario, the closing assets prior to withdrawal are $985,000, leaving the Closing Pro-forma Shadow NAV at 98.13%, which breaks the buck. The withdrawals get paid at a 8.48% discount. Those staying still have all of their units at greater than par.

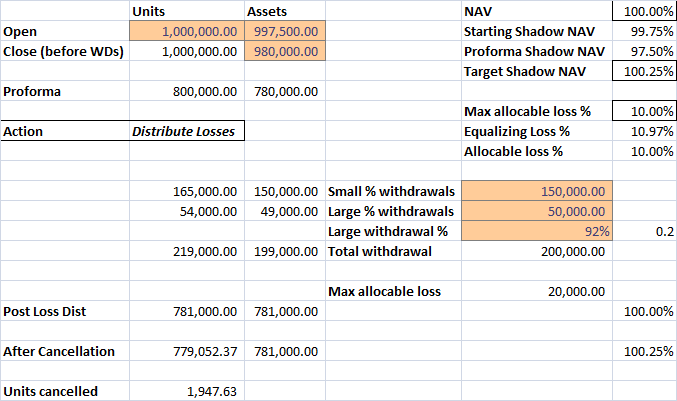

In the fourth scenario, the closing assets prior to withdrawal are $980,000, leaving the Closing Pro-forma Shadow NAV at 97.50%. The withdrawals get paid at a 10.00% discount. Those staying also lose units, but their higher income rate will compensate for that, unless the losses are permanent from defaulted assets. Nonetheless, the losses they take are minor relative to those who withdrew from the MMF.

In the fifth scenario, the meltdown scenario worse than Reserve Primary, the closing assets prior to withdrawal are $950,000, leaving the Closing Pro-forma Shadow NAV at 93.75%. The withdrawals get paid at a 10.00% discount. Those staying also lose units, but their higher income rate will compensate for that, unless the losses are permanent from defaulted assets. Nonetheless, the losses they take are less than those who withdrew from the MMF.

My contention is this: a structure like this would prevent money market panics. Would it stop something like the Great Financial Crisis? (2008-9) Of course not. The disaster was going to happen regardless. The money market funds were in the wrong place at the wrong time. The repo markets were far more significant, and still have not gotten fixed.

When I get a moment, I will submit this to the SEC, as I did the last time after the Great Financial Crisis. I talked with two of the lawyers at the SEC, who said my idea was promising, but too radical. We’ll see what happens this time. It will likely be nothing, but who can tell? Gensler might be willing to consider something radical.