No es ESG

Picture Credit: David Merkel || E & S are hollow, G is solid

There are fads in investing. They eventually go away. Remember ARM funds? The Americus Trusts? (Neat idea, killed by a legal change). The nifty fifty? Hot industries that produce a lot of IPOs?

I also think cryptocurrencies are a fad, and also factor and volatility investing, at least in terms of the ETFs that are offered to retail investors.

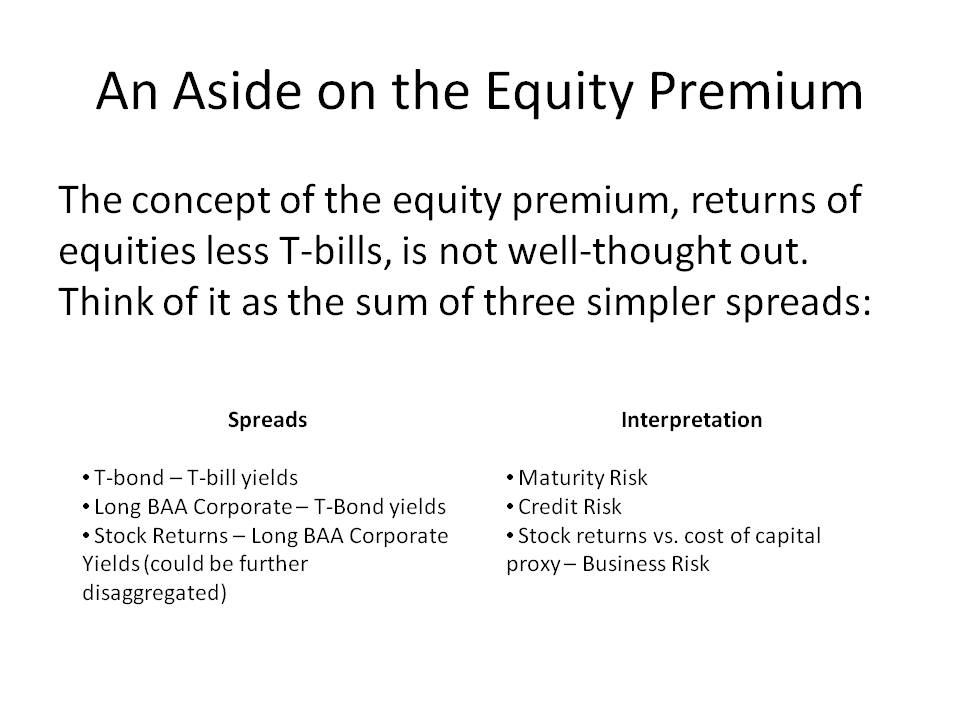

And, I think ESG is a fad, at least in terms of the way it is being deployed today. My main point is that E (environmental) & S (social) are mostly subjective, and not related to investment returns or risk control. G (governance) is mostly objective and related to investment returns and risk control.

Now some will say “But wait, there are all these journal articles showing that ESG produces better volatility-adjusted returns.” Quantitative finance has a laundry list of problems:

- We have only one world, one history, one data set. We’ve gone over the data set numerous times, knowing its proclivities. It’s not hard to tease “alpha” out in a study, but it is difficult to realize alpha in real life.

- Researchers often take multiple passes over the data set as they do their analyses. Only the ones with results supporting the expected conclusions get a paper published.

- Neutral observers don’t exist — their pay and social standing get determined by producing a series of statistically significant results, regardless of whether they tortured the data to get there or not. (Aside: when I read some of the macroeconomic crud out of the Federal Reserve, and I see the abstruse technique employed to get a result, I know the data has been tortured, and of course the model does not predict well.)

- And more — you can read this for the rest of the problems. I don’t think I even get all of the issues with academic-style research in that article.

As such, I don’t trust the research on ESG. The limited history that we have for general inquiries is even shorter for ESG analyses. The likelihood of picking up spurious correlation is high. As such, unless I have a good mental model for how environmental or social issues affect long-term growth in value, I can’t use them as a fiduciary. I have those mental models for governance, so I use them — just not the same way as some of the quantitative governance models do.

Governance issues are perennial; they are not a fad. The agency problem, where corporate managements pursue goals that are in their interests, but not in the interests of shareholders never goes away. It can be reduced by a variety of measures, like splitting the CEO and Chairman positions. removing management influence over the audit and compensation committees, end things like that.

That said, there are exceptions to the rules, and certain strong managers running companies with highly focused and ethical cultures might be allowed more running room. Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t fit most of the rules, and in general it has done well. One size fits most, but not all.

It’s similar to the way I view management use of free cash flow. With a talented and honest management team, I want the management to have the freedom to retain all of the cash flow for growth if they see the opportunities. But most managements aren’t that good, and they should pay a dividend. Buybacks should only be done when the stock is notably cheap compared to the private market value of the firm, and the balance sheet remains solid.

That’s why I think many simple governance scores are mistaken. You have to take a look at the management team and culture in order to do a broader evaluation of the governance. I for one a comfortable buying stakes in a company where there is a control investor if the control investor is known for treating the outside passive minority investors fairly, and does not scrape too much off the top.

I expect companies that I own to follow the laws of the countries that they work in, and engage in ethical behavior. My rule is simple: if a company tries to cheat one set of stakeholders, the odds are higher that they will cheat shareholders at some point. Most of my significant losses have stemmed from some sort of fraud issue… this is etched in my mind.

But many of the details of environmental and social factors seem utterly tangential to me — I don’t see how they drive value. Let the government press its claims on corporations to avoid discrimination and limit pollution. That is the proper locus for these issues, particularly if you are a fiduciary. What is in the best financial interests of your clients should be your guiding principle.

Note as well that the implementation of E, S, and G are nowhere near standardized. G is probably the closest. (This also applies to factor investing as well, which is constantly engaging in new specification searches sharpening their statistical analyses.) Even if I wanted to do E & S, how would I know that I have the right figures? How would I know that they weren’t a product of backtest biases?

Also, as Matt Levine points out, many applications of ESG don’t make a lot of sense, even if these were desirable goals. As such, I look at many of the ESG products being put out there are marketing fads to take the attention of retail away from earning returns… after all, it is tough to beat the market, and ESG will give you many ways to have have a built-in excuse.

Do I know that I am in a minority for my views here? Yes. But I am often in a minority, and I would argue that the degree of agreement with ESG is paper-thin. It’s good while it brings in assets to manage, but the moment it doesn’t bring home the bacon, it will be jettisoned.

I’m in the minority for now. I expect the majority to come my way, not vice-versa. No illusions — it will take time for that to happen.