This should be my last post on Trills.? Let me begin it by suggesting that we sell all of our national parks (and other land owned by the US Government) to the Saudis in exchange for forgiveness of our debts.? Wait, we could do better.? Disney could create theme parks, even on the national mall, making being American far more fun than the stuffy Smithsonian.

What’s that you say?? We are selling our patrimony?? How dare we sell our precious resources to exploiters/foreigners?? Uh, times are tough, and much as we make paper promises, eventually something hard and enduring has to back them up.

I feel the same way about Trills.? If the US Government ever were to sell trills, it would be the same as selling away a share in the take from the IRS in perpetuity.? Selling shares in the IRS, ridiculous, right?? Well, that is what a trill is — selling a share of the IRS.

Imagine that the US Government taxes at 20% of GDP, and then they sell Trills equal to 1% of GDP.? Initially, the US? Government would get a flood of cash, but would have given up 5% of their income stream.? If we had angels running our government, focusing on long-term projects, I would not object so much, but we spend in the present and neglect the future.

A government that issues Trills reduces its flexibility.? Initially not so, they get a lot of cash in, and don’t have to put a lot out.? The US government at present has explicitly issued debt with a market value around 75% of GDP.?? Implicitly, the funding shortfall when you add in the excess liabilities from the entitlements is 400% of GDP.

To keep things simple, let’s assume that the initial yield of Shiller’s trill is correct (1%), not only for small amounts of issuance, but large amounts.? That is probably a bad assumption in this case, after all, the proportion of Treasury issues out past 20 years is a small minority of Treasury issuance, and even with existing demand, the yield curve is quite steep.? Trills, being perpetual bonds with a growing coupon, are longer than any fixed income instrument that I have ever seen, so if they were issued in large amounts, who knows what the initial yields would be?

(Note to potential investors: if trills ever see the light of day, they could be an interesting buy, but I would let the first few auctions pass until the curve gets satiated and the initial coupon rises to a higher level, i.e., the price falls for all trills. You might even wait for the government to announce the last trills auction to buy.? One thing about trills — every issuance will raise additional doubts about ever being paid back.? They would be more valuable when the government says it won’t create any more of them.)

So, back to the application, imagine the US government auctioning off $11 Trillion (yes, with a “Tr”, not a “B”) of trills to retire the explicit debt.? Assume that the 1% initial coupon holds — we have now walled off 0.75% of GDP as a permanent expense in the Federal budget — keeping the numbers simple, that would be 3.75% of all Federal revenues in perpetuity.? Doesn’t sound like much, but we replace the existing debt with a exponentially growing stream where debt service is initially $110 billion.? That could help balance the budget at present, but at a cost to all future generations, until the US shall be no more.

Now, the 1% initial coupon would not hold for such large issuance.? Say the coupon ends up being 2%.? Now 7.5% of Federal revenues are dedicated to debt service in perpetuity, and 1.5% of GDP.

This would become addictive to the US Government — trills raise a lot of money relative to their initial cashflows, and they have no rollover risk.? Now imagine the US issuing a present value of $70 Trillion in trills (5x current GDP) over the next 30 years to roll over existing debt, take care of all the unfunded liabilities, and cover all of the structural deficit for the next 10 years.? At my assumed coupon of 2%, that would wall off 10% of GDP in perpetuity, or half of Federal revenues to pay for the sins of the past.? The bad human proverb recorded in the Bible might return to common parlance, “The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge.”? (Note: at/near the exile of Judah, some complained they were being punished for the sins their forbears committed, and not their own sins.? God corrects the proverb, saying that people are punished for their own sins.)

Potentially, trills are a heavy burden to place on all future generations for the fiscal profligacy of the last 80 years.? I would rather not see trills see the light of day as a result.? It would postpone the eventual day of reckoning where the US Government would have to slim down dramatically, and live within its budget.? Trills would make the US government more reckless, not more cost conscious.

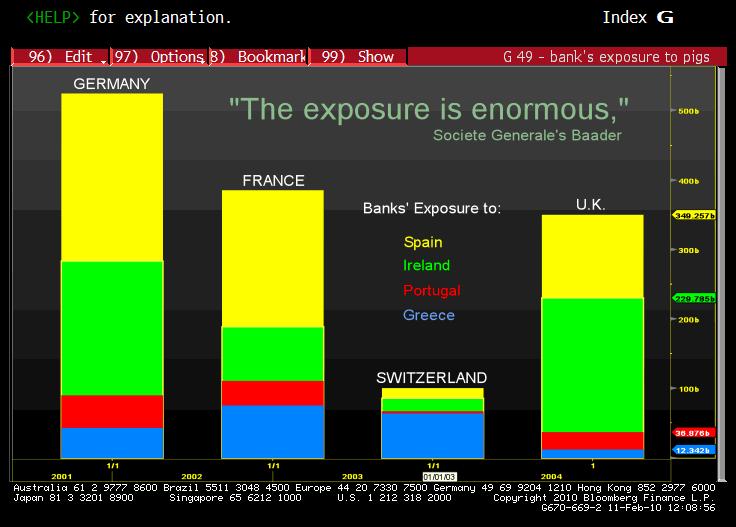

But, if trills are to be issued, let some more desperate entity issue them first, like Greece or California, and then let the rest of us watch the consequences.? They would provide help in the short run, at a likely cost of a bigger failure later, with more damage to creditors, and the general economy.

This should be my last piece on this, though one final thought tugs at me — the derivatives market that would grow up around trills would be a hoot.? GDP futures and options, stripping coupons to create discount trills and income trusts.? The investment bankers would have a field day, with the cheap cost of burdening all future generations, who I am sure will remember Dr. Shiller warmly.

My comment:

My comment:

I write a daily piece on financials for my company’s clients.? The stock of the GSEs rose because the odds of them digging out of the hole increased.? You can’t dig out of the hole if you are dead, so when you are near that boundary, even small changes in the distance from death can affect sensitive variables lke the stock price.? Plus, the odds rise that the US will do something really dumb, like convert theor preferred shares to common.

4) Kid Dynamite put up a good post on CDOs, I commented:

KD, maybe we should play chess sometime. Spotting a queen and rook is huge. I have beaten Experts, though not Masters on occasion (except in multiple exhibitions), and I can’t imagine losing to anyone who has spotted me a rook and queen.

All that said, I never gamble, and as an actuary, I know the odds of most games that I play.

Now, all of that said, I never cease to be amazed at all of the dross I receive in terms of ideas that look good initially, but are lousy after one digs deep.

Good post. Makes me wonder how I would have done in the same interview. Quants need to have a greater consideration of qualitative data. When I was younger, I didn’t get that.

5) Then again, Yves Smith comments on a similar issue at her blog.? My comment:

I?m sorry, but I think jck is right. The risk factors were clearly disclosed. Buyers should have known that they were taking the opposite side of the trade from Goldman.

As I sometimes say to my kids, ?You can win often if you get to choose your competition,? and, ?Winning in investing comes from avoiding mistakes, not making amazing wins.?

As a bond manager, I was offered all manner of amazing derivative instruments. I turned most of them down. Most people/managers don?t read the prospectus, but only the term sheet. Not reading the prospectus is not doing due diligence.

Since we are on the topic of Goldman Sachs, in 1994, an actuary from Goldman came to meet me at the mutual life insurer where I worked. I wanted to write floating rate GICs which were in hot demand, and all of my methods for doing it were too risky for me and the firm.

Goldman offered a derivative instrument that would allow me to not take too risky of an investment strategy, and credit an acceptable rate on the GIC. So, as I read through the terms at our meeting, a thought occurred to me, and so I asked, ?What happens to this if the yield curve inverts??

He answered forthrightly, ?It blows up. That?s the worst environment for these instruments.? Now, if you read the docs, it was there, and when asked, he told the truth. The information was not up front and volunteered orally.

But that?s true of almost all financial disclosures. You have to read the fine print.

As for the derivative instruments, in early 2005, many large financial institutions took billion dollar writedowns. All of my potential competitors in the floating rate GIC market left the market. I went back to buyers, and offered the idea that I could sell them the GICs at a lower spread, which would give them a decent return, but with adequate safety for my firm. All refused. They basically said that they would wait for the day when the willingness to take risk would return.

And it did, until the next blowup in 1998 around LTCM.

My lesson: the craze for yield drives many derivative trades. What cannot be achieved with normal leverage and credit risk gets attempted, and blows up during hard times.

Structure risks are significant; the give up in liquidity is significant. The big guys who play in these waters traded away liquidity too cheaply, and now they are paying for it.