Before I start this evening, I want to comment on what posts were popular while I was gone. Here they are, in declining order of popularity:

The first thing that fascinates me is how different these articles are. Second, the first two articles are old — 2011 and 2008 respectively. There are a few math pedagogy articles at my blog, but not many. It is something near to my heart as math was my favorite subject as a boy, followed by science and the social sciences.

It also highlights the peculiarity of my blog. I cover a lot of ground, and I am fairly certain that every post loses some of my audience. Anyway, it is nice to be doing this again. I hope you all enjoy it. And to Tadas Viskanta at Abnormal Returns, thanks for taking note of my return. That meant a lot to me.

On to tonight’s post:

======================================================

A friend of mine wrote this to me:

I am VERY interested to have your opinion on this.? First a few assumptions.? While equality of opportunity in a free market economy is ideal and a goal to be pursued, equality of outcome is both impossible and not something to be pursued for many reasons, including the consequences of stifling innovation and competition.?

?

The question – While there will always be income inequality in a free market economy, does crony capitalism have the effect of increasing income equality by means of subsidies, regulations, protection of monopolies, etc?

?

The reason for the question is this:? I think that my lefty friends are on to something when they point out the gross disparity of income that exists in our country.? They believe that the solution is bigger government and something that looks more and more like socialism.? I am arguing that smaller government, more local control, and slowly killing crony capitalism will result in more fairness.??

?

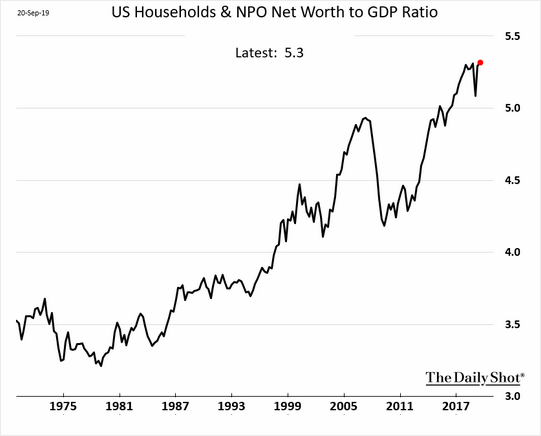

In this Forbes article from May of last year, the author notes that a typical CEO in the 1950s earned about 20x the amount of the average worker whereas today the number is 361x.? Is this actually deserved?? I understand that there is and should be a disparity here but isn’t some part of this disparity due to distortion of markets caused by government policy?? Brink Lindsey in this National Review article makes the case that it is and that conservatives need to recognize it.

?

What say you?

This may sound a little noncommittal, but inequality of income is partly due to the government, technology, culture, and part is unavoidable, regardless of the technology, or social or governmental structures. Let me take each in order.

Yes, big government likes big labor and big business, and it tends to squeeze out smaller businesses. Part of this is a matter of convenience — if you are big, it would be nice to have a “one stop” solution. It is a lot more expensive for small businesses to comply with regulations in relative terms.

I recognize that problem as a state-regulated RIA. If I wanted to get bigger, the initial phase of it would require a lot more work. I can stay at the level I am, and do it all myself, and keep my offering simple. Personally, I like that, because I think it is best for my clients, but if I just wanted to gather assets to enrich myself, the next phase would be difficult. Once you are big, it gets a lot easier. You can spread the fixed costs of regulation over a much wider revenue stream.

Also, the government is focused on creating “jobs.” Though politicians may inveigh about creating high-paying manufacturing jobs, the statistical apparatus measures all jobs, and that is what receives the most attention. Unemployment is low, but the share of total income going to labor is also low.

When enterprises get larger, the pay differential will naturally increase, as those in a hierarchy derive some income from the oversight of those below them, whether it is done well or not. Enterprises are larger now than in the 1950s.

Technology can encourage or discourage income inequality. Information technology has helped to eliminate a lot of middle income jobs, as information technology allows the same things to be done with lesser-skilled people, whether here in the US, or abroad.

This brings up another unpopular point: though inequality may be increasing in the developed world and China, it is decreasing globally, as lower paid workers abroad get much better pay doing work that otherwise would be done in developed countries. Since we increasingly have a global economy, and that economy is becoming more equal, why should we be so concerned about the local effects in the US?

That brings up the social and unavoidable aspects of inequality, which are less popular to consider. Many younger people in developed nations consider prosperity to be their birthright, and work less hard in school than their peers in developing nations. Is it any surprise that incomes to those who are lazy lag, or even decline? This phenomenon is well-known, all the way back to ancient Greece, if not further. “Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” is well-known phrase, expressing how the children of the wealthy get lazy, and wealth is lost.

This is the main reason why I doubt that the same families will maintain their dominance, even as inequality persists. The elites rotate over time, as Pareto taught. It is not a fixed class structure, as in the times where ownership of land dominated, but the names and faces change as fortunes are won and lost.

Our current educational establishment is turning out children that are less bright than their parents. If the children are less bright or motivated than their competition, will their incomes not sag? America does better than most other countries in aggregate as we give people more freedom, and teach them to be flexible. But that doesn’t mean that the children will do better than their parents.

We also accept more immigrants (as does Canada) who are motivated by the freedom to grow their enterprises. This is another aspect of some of the xenophobia in the US as some rural natives resent wealthy immigrants who don’t share their values.

Summary

I tried to teach my children to be industrious, smart, and pursue occupations that would make a difference for them and their families. Only a few of them listened, and they are doing well. That is America in microcosm.

Yes, you can argue about big government, labor, and business, but that is only a part of the puzzle. Incomes might become more equal if Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb could level the taxi and hotel industries, which have government regulations protecting them. Removing regulations tends to gore those in the middle class that are protected by the regulations versus those that want to be in the middle class that would like to compete against them.

What matters most is the culture of a nation, and how they are motivating the next generation to compete. We are doing that moderately badly, and that accounts for the relative loss of stature of the USA versus the rest of the world. This places the blame on the American people themselves, as they have not committed to having a culture of excellence, and getting their children to implement that.