You Can Get Too Pessimistic

Entire societies and nations have been wiped out in the past. ?Sometimes this has been in spite of the best efforts of leading citizens to avoid it, and sometimes it has been because of their efforts. ?In human terms, this is as bad as it gets on Earth. ?In virtually all of these cases, the optimal strategy was to run, and hope that wherever you ended up would be kind to foreigners. ?Also, most common methods of preserving value don’t work in the worst situations… flight capital stashed early in the place of refuge?and?gold might work, if you can get there.

There. ?That’s the worst survivable scenario I can think of. ?What does it take to get there?

- Total government and?market breakdown, or

- A lost war on your home soil, with the victors considerably less kind than the USA and its allies

The odds of these are very low in most of the developed world. ?In the developing world, most of the wealthy have “flight capital” stashed away in the USA or someplace equally reliable.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=-=-=-

Most nations, societies and economies are more durable than most people would expect. ?There is a cynical reason for this: the wealthy and the powerful have a distinct interest in not letting things break. ?As Solomon observed a little less than 3000 years ago:

If you see the oppression of the poor, and the violent perversion of justice and righteousness in a province, do not marvel at the matter; for high official watches over high official, and higher officials are over them. Moreover the profit of the land is for all; even the king is served from the field. — Ecclesiastes 5:8-9 [NKJV]

In general, I think there is?no value in preparing for the “total disaster” scenario if you live in the developed world. ?No one wants to poison their own prosperity, and so the?rich and powerful?hold back from being too rapacious.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=-=-=-

If you don’t have a copy, it would?be a good idea to get a copy of?Triumph of the Optimists. ?[TOTO] ?As I commented in my review of TOTO:

TOTO points out a number of things that should bias investors toward risk-bearing in the equity markets:

-

Over the period 1900-2000, equities beat bonds, which beat cash in returns. (Note: time weighted returns. If the study had been done with dollar-weighted returns, the order would be the same, but the differences would not be so big.)

-

This was true regardless of what presently developed nation you looked at. (Note: survivor bias? what of all the developing markets that looked bigger in 1900, like Russia and India, that amounted to little?)

-

Relative importance of industries shifts, but the aggregate market tended to do well regardless. (Note: some industries are manias when they are new)

-

Returns were higher globally in the last quarter of the 20th century.

-

Downdrafts can be severe. Consider the US 1929-1932, UK 1973-74, Germany 1945-48, or Japan 1944-47. Amazing what losing a war on your home soil can do, or, even a severe recession.

-

Real cash returns tend to be positive but small.

-

Long bonds returned more than short bonds, but with a lot more risk. High grade corporate bonds returned more on average, but again, with some severe downdrafts.

-

Purchasing power parity seems to work for currencies in the long run. (Note: estimates of forward interest rates work in the short run, but they are noisy.)

-

International diversification may give risk reduction. During times of global stress, such as wartime, it may not diversify much. Global markets are more correlated now than before, reducing diversification benefits.

-

Small caps may or may not outperform large caps on average.

-

Value tends to beat growth over the long run.

-

Higher dividends tend to beat lower dividends.

-

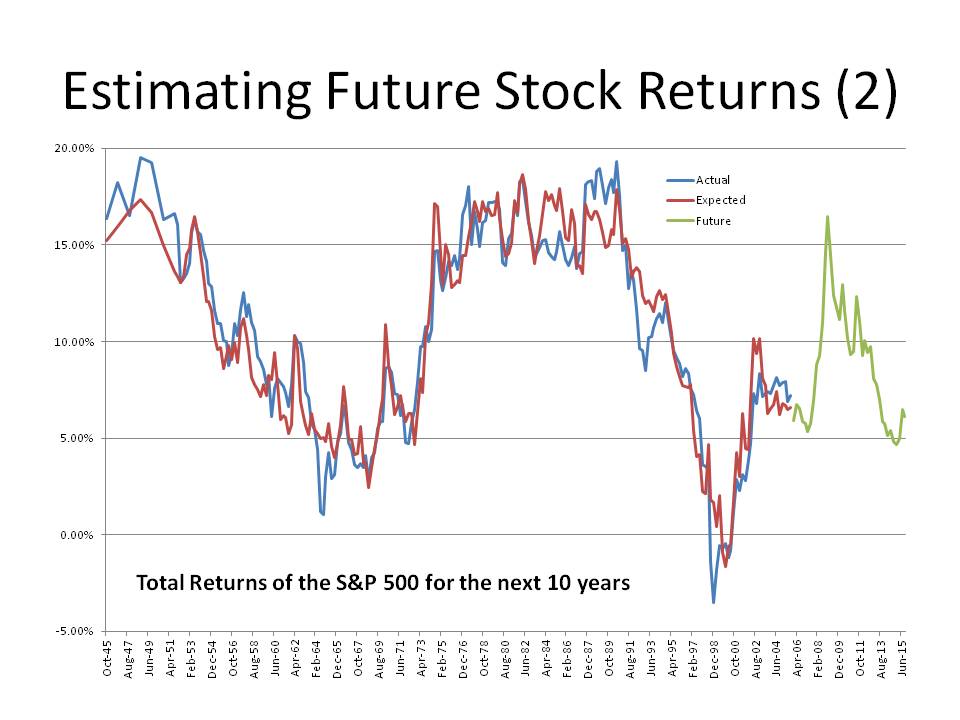

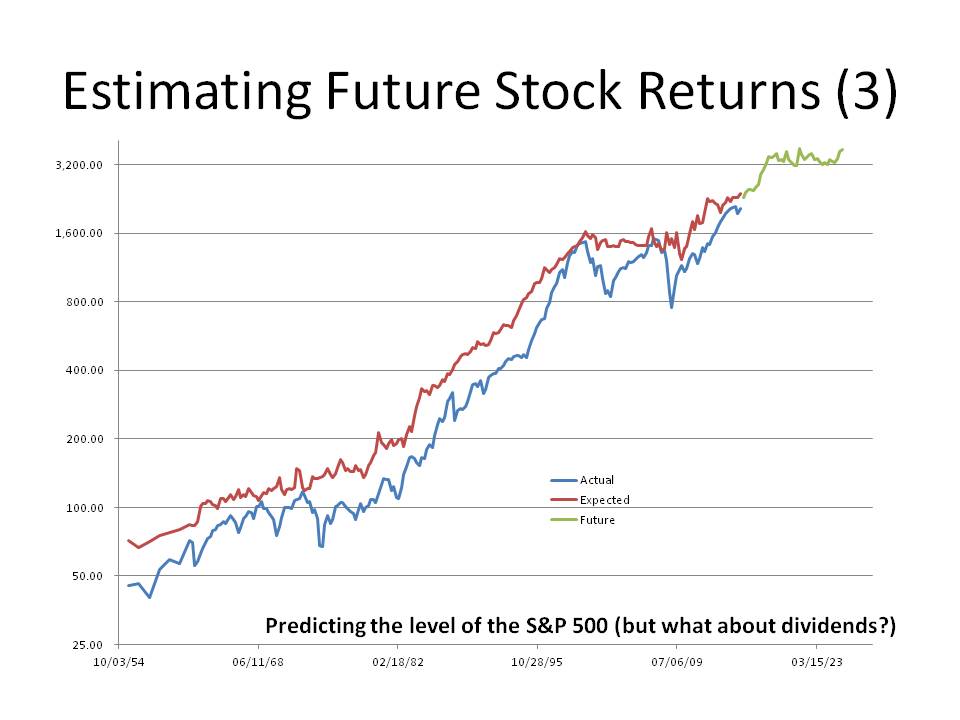

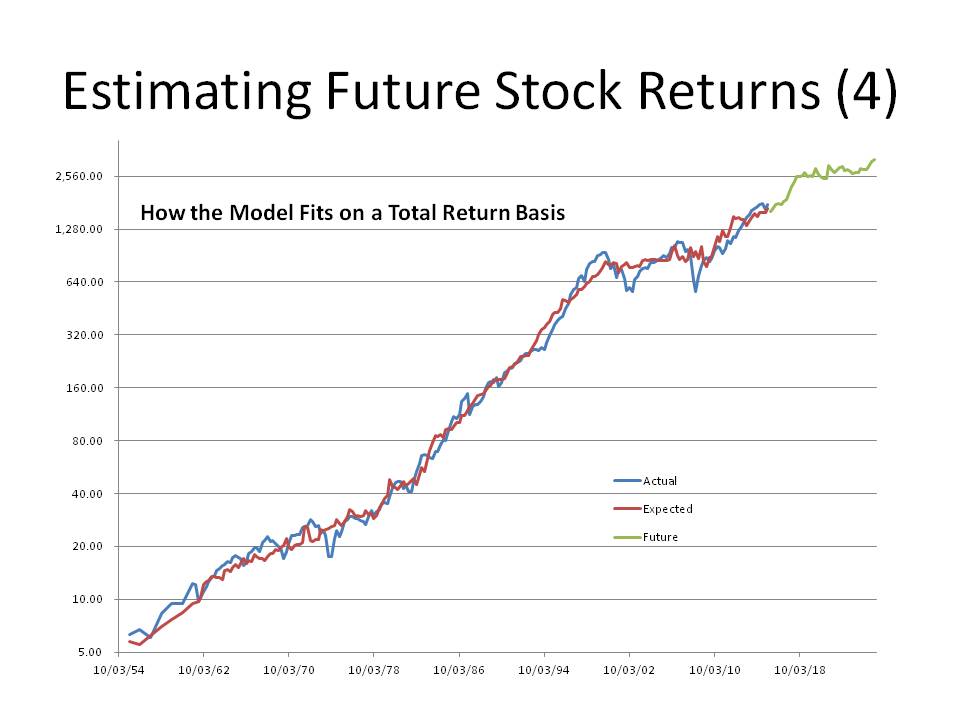

Forward-looking equity risk premia are lower than most estimates stemming from historical results. (Note: I agree, and the low returns of the 2000s so far in the US are a partial demonstration of that. My estimates are a little lower, even?)

-

Stocks will beat bonds over the long run, but in the short run, having some bonds makes sense.

-

Returns in the latter part of the 20th century were artificially high.

Capitalist republics/democracies tend to be very resilient. ?This should make us willing to be long term bullish.

Now, many people look at their societies and shake their heads, wondering if things won’t keep getting worse. ?This typically falls into three?non-exclusive buckets:

- The rich are getting richer, and the middle class is getting destroyed ?(toss in comments about robotics, immigrants, unfair trade, education problems with children, etc. ?Most such comments are bogus.)

- The dependency class is getting larger and larger versus the productive elements of society. ?(Add in comments related to demographics… those comments are not bogus, but there is a deal that could be driven here. ?A painful deal…)

- Looking at moral decay, and wondering at it.

You can add to the list. ?I don’t discount that there are challenges/troubles. ?Even modestly healthy society can deal with these without falling apart.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=-=-=-

If you give into fears like these, you can become prey to a variety of investment “experts” who counsel radical strategies that will only succeed with very low probability. ?Examples:

- Strategies that neglect investing in risk assets at all, or pursue shorting them. ?(Even with hedge funds you have to be careful, we passed the limits to arbitrage back in the late ’90s, and since then aggregate returns have been poor. ?A few niche hedge funds make sense, but they limit their size.)

- Gold, odd commodities — trend following CTAs can sometimes make sense as a diversifier, but finding one with skill is tough.

- Anything that smacks of being part of a “secret club.” ?There are no secrets in investing. ?THERE ARE NO SECRETS IN INVESTING!!! ?If you think that con men in investing is not a problem, read?On Avoiding Con Men. ?I spend lots of time trying to take apart investment pitches that are bogus, and yet I feel that I am barely scraping the surface.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=-=-=-

Things are rarely as bad as they seem. ?Be willing to be a modest bull most of the time. ?I’m not saying don’t be cautious — of course be cautious! ?Just don’t let that keep you from taking some risk. ?Size your risks to your time horizon for needing cash back, and your ability to sleep at night. ?The biggest risk may not be taking no risk, but that might be the most common risk economically for those who have some assets.

To close, here is a personal comment that might help: I am natively a pessimist, and would easily give into disaster scenarios. ?I had to train myself to realize that even in the worst situations there was some reason for optimism. ?That served me well as I invested spare assets at the bottoms in 2002-3 and 2008-9. ?The sun will rise tomorrow, Lord helping us… so?diversify and take moderate risks most of time.