One of the best things for me regarding blogging are the readers who ask me questions. ?When I get a set of them that are general enough, I answer them for all my readers, after stripping out identifying data. ?Here is the most recent:

One of the best things for me regarding blogging are the readers who ask me questions. ?When I get a set of them that are general enough, I answer them for all my readers, after stripping out identifying data. ?Here is the most recent:

Thank you for your work on your blog which I read with great interest!

I would have a question for you regarding private equity vs. public traded stocks:

– Does a private investor who is investing/saving for?retirement?need?private equity investments?

– Does such an investor make a big mistake if only investing in publicly traded stocks?

– Do you also invest in private equity?

– Is there any evidence that private equity is outperforming simple passive index investing?

?Many thanks for your time and all the best.

Before I answer the questions, let me take a step backward, and be a little more general, asking a few questions of my own:

1) If you wanted to invest in private equity, how would you do it?

2) What are some of the disadvantages and advantages of investing in private equity?

3) Why don’t?amateur investors invest in just a few public stocks?

Okay, here goes:

If you wanted to invest in private equity, how would you do it?

There are two ways to do it, and I have done each one in my life:

a) invest in a private equity fund

b) invest in a friend’s business

I’m going to ignore the new phenomenon of crowdsourcing, because it is too new to evaluate. ?Wait for it to mature before committing funds.

Now, investing in a private equity fund usually requires being an accredited investor, because the legal form is that of a limited partnership, and those who invest in that are supposed to be sophisticated investors who can afford to lose it all.

Now, in my days of working inside insurance companies, late in?the ’90s, it was all the rage for life insurers to invest in private equity funds. ?I remember being brought in to vet deals after my boss had informally set his heart on doing them. ?As you might guess, I was not too crazy about a tech-heavy fund that was investing in dot-coms, still, we ended up doing it. ?I liked better a?private equity fund that was investing in small and medium-sized ordinary businesses in the Mid-Atlantic region.

We invested in both of them; neither one ended up returning the capital to the insurance company. ?Just because?the institution?is big enough to be a Qualified Institutional Buyer does not mean that it has?the smarts to actually evaluate the risks taken?on. ?Similarly, just because you are an “Accredited Investor” doesn’t mean you are capable of evaluating the risks you will be taking. ?All it means is that the government won’t stand in the way of you losing money that they keep the little guys from losing.

As for investing in a friend’s business, I have done it twice, and so far, seemingly successfully with each: Wright Manufacturing and Scutify. ?You don’t have to be accredited to be an angel investor, but it can be a take it as it comes sort of thing if you don’t live in an area where lots of new ventures get created.

In these situations, it is?good if you bring more than capital to the table. ?Particularly with Wright Manufacturing, I have tried to make my help available when needed when the firm has faced challenges.

What are some of the disadvantages and advantages of investing in private equity?

Disadvantages

- Illiquid — in a fund, you are locked up for years. ?Investing in a friend’s business means you are at the mercy of the firm and other shareholders if you want to buy more or sell some. ?If you think bid/ask spreads for illiquid public stocks are wide, they are narrow compared to owning shares in a private business.

- The management has information advantages, whether it is the fund or the friend’s business.

- The variability of results is very high, with many investments being total losses. ?As true of public equities, don’t invest what you can’t afford to lose.

- Your friend may try to raise capital at times where you can’t or don’t want to participate.

- You may not get the same amount of data to analyze as with a public company; then again, you may get the inside scoop.

Advantages

- The fund could have genuine professionals sourcing business prospects otherwise unavailable to most for investment.

- Your friend could really be onto something big.

- There is the remote possibility of hitting a home run and making a return many times greater than your capital.

- Sometimes there are tax advantages (say, for creating manufacturing jobs in Maryland).

- Stock prices are not posted for you, and so you don’t panic so easily, and after all, you would have a hard time selling.

Why don’t?amateur investors invest in just a few public stocks?

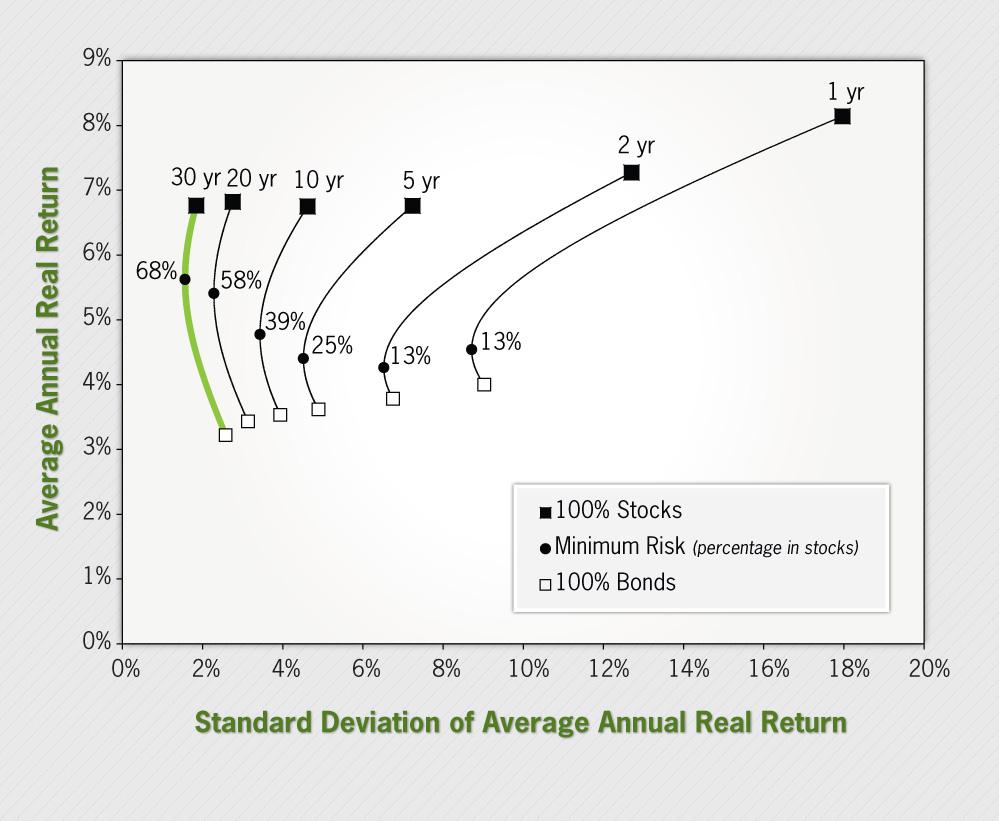

Most amateur investors are not good enough at business to find a few superior?businesses and hang onto only those. ?Don’t feel bad, though, that’s true of almost all professionals. ?Diversification is the only free lunch in the business,?because it reduces the variability of returns. ?If you think investors do badly panicking with diversified funds as in 2008-9, if they were only holding a few companies, the volatility would be so great that many more would lose confidence.

The upshot here is that the results of own shares in just a few private companies will vary tremendously; most people will not be able to live with that level of variability,?lack of liquidity, and lack of control.

So, onto my reader’s?questions:

Do you also invest in private equity?

I have done so, as I have said, but most of my investments are in public equities following my own strategies. ?My?asset allocation would look something like this:

- Public equities 55%

- Private equities 15%

- House 15%

- Bonds & cash 15%

- No debt

Does a private investor who is investing/saving for?retirement?need?private equity investments?

Need it? No. ?Could you use it if accredited, or investing in the businesses of friends? Yes.

Does such an investor make a big mistake if only investing in publicly traded stocks?

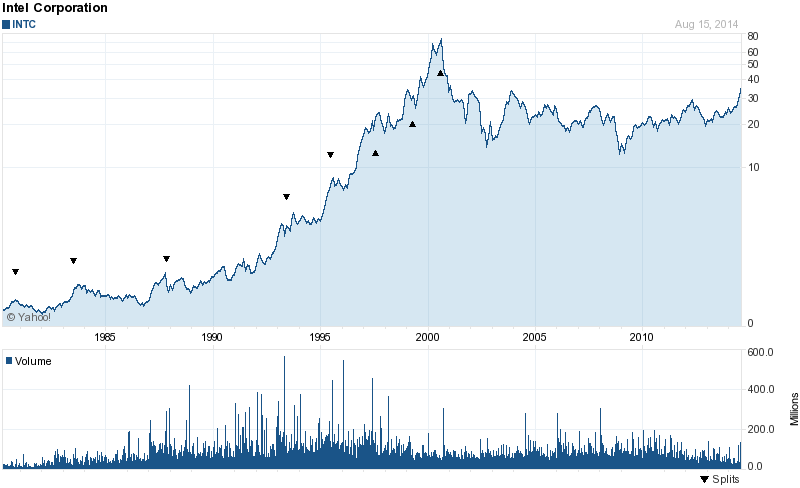

No. ?Think of it this way — private equity tends to do about as well as leveraged index funds, on average. ?A portfolio of private equity and bonds will do about as well as some equity index funds, on average, with a much wider degree of variation than the index funds.

As an aside, to two private firms in which I hold shares carry little debt. ?That lowers my risk.

Is there any evidence that private equity is outperforming simple passive index investing?

It does better in good times on average, and worst in bad times, and is far more variable. ?One note, be careful about some of the Internal Rate of Return [IRR] figures that some private equity funds trot out. ?The returns are overstated because the capital is drawn on slowly, which inflates the IRR. ?That said, investors have to plan for that capital to be drawn, and must have some slack assets earning less to fund the later draws on capital. ?If that cost were factored in, the IRR would go down considerably.

In Closing

If I were talking to an amateur investor who wanted to run a concentrated portfolio of value stocks in the public markets, I would say, learn a lot, and put in enough time to make it a second job. ?The same would be more true for the fellow attempting to do the same thing in private equity — it is harder.

If I were talking with an amateur investor trying to find a very good?mutual fund manager or registered investment adviser [RIA] for his funds, I would tell him to look carefully for active share, is?the process sensible and repeatable, etc. ?If he were accredited, and wanted to do the same for private equity, I would be inclined to tell him to hire a specialist consultant to find it for him, because the data is not as available, and the games are more opaque. ?Add in that the big, respected names stick with institutions as clients — smaller amounts of money will have to find a good manager that is also off the beaten track.

So no, there is no advantage to private equity after taking into account the disadvantages. ?Both of my investments have had more than their share of ups and downs; I don’t think the average person is made for that.