1) The blog was out of commission most of Saturday and Sunday, for anyone who was wondering what happened. From my hosting provider:

We experienced a service interruption affecting the Netfirms corporate websites and some of our customer hosted websites and e-mail services.

During scheduled power maintenance at our Data Centre on Saturday Feb. 23 at approximately 10:30 AM ET, the building’s backup generator system unexpectedly failed, impacting network connectivity. This affected several Internet and Hosting Providers, including Netfirms.

Ouch. Reliability is down to two nines at best for 2008. What a freak mishap.

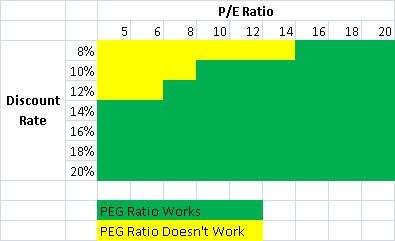

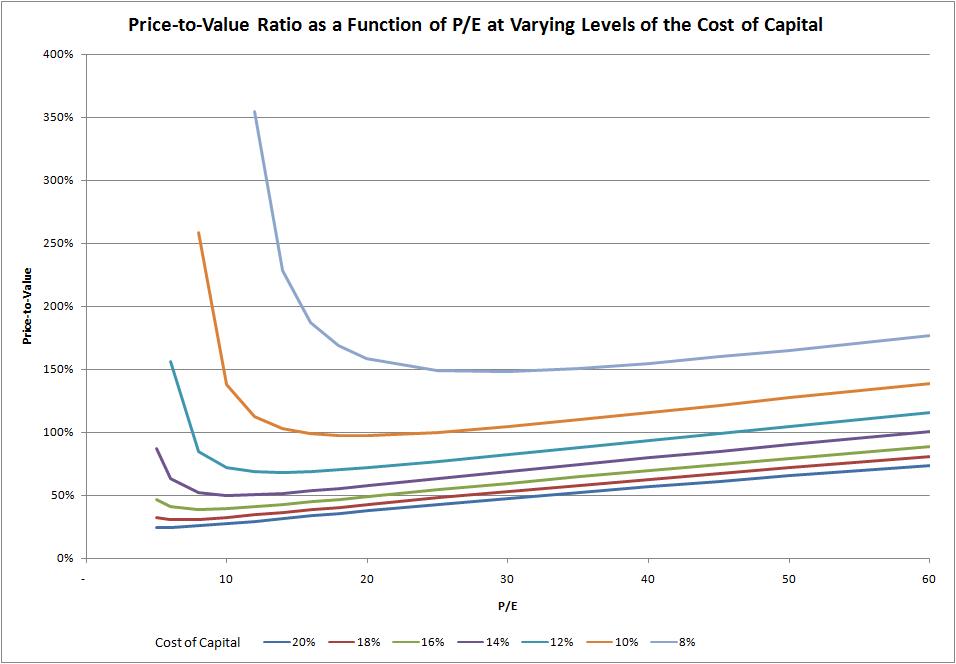

2) Thanks to Bill Rempel for his comments on my PEG ratio piece. I did not have access to backtesting software, but now I do. I didn’t realize how much was available for free out on the web. He comes up with an interesting result, worthy of further investigation. My main result was that PEG ratio hurdles are consistent with a DDM framework within certain moderate values of P/E and discount rates. Thanks also to Josh Stern for his comments.

3) I posted a set of questions on Technical Analysis over at RealMoney, and invited the technicians to comment.

|

|

David Merkel |

| Professionals are Overrated on Fundamental Analysis |

2/21/2008 5:19 PM EST

|

I’m not here to spit at technicians. I have used my own version of technical analysis in bond trading; it can work if done right. But the same thing is true of fundamental investors, including professionals. There are very few professional investors that are capable of delivering above average returns over a long period of time. Part of it is that there are a lot of clever people in the game, and that raises the bar.

But I have known many good amateur investors that do nothing but fundamental analysis, and beat the pros. Why? 1) They can take positions in companies that are too small for the big guys to consider. 2) They can buy and hold. There is no pressure to kick out a position that is temporarily underperforming. With so many quantitative investors managing money to short time horizons, it is a real advantage to be able to invest to longer horizons amid the short-term volatility. 3) They can buy shares in companies that have been trashed, without the “looks that colleagues give you” when you propose a name that is down over 50% in the past year, even though the fundamentals haven’t deteriorated that much. 4) Individual investors avoid the “groupthink” of many professionals. 5) Individual investors can incorporate momentum into their investing without “getting funny looks from colleagues.” (A bow in the direction of technical analysis.)

When I first came to RM 4.4 years ago, I asked a question of the technicians, and, I received no response. I do have two questions for the technicians on the site, not meant to provoke a fundy/technician argument, but just to get opinions on how they view technical analysis. If one of the technicians wants to take me up on this, I’ll post the questions — hey, maybe RM would want to do a 360 on them if we get enough participation. Let me know.

Position: none

|

|

David Merkel |

| The Two Questions on Technical Analysis |

2/22/2008 12:15 AM EST

|

I received some e-mails from readers asking me to post the questions that I mentioned in the CC after the close of business yesterday. Again, I’m not trying to start an argument between fundies and techies. I just want to hear the opinions of the technicians. Anyway, here goes: 1) Is there one overarching theory of technical analysis that all of the popular methods are applications of, or are there many differing forms of technical analysis that compete against each other for validity (and hopefully, profits)? If there is one overarching method, who has expressed it best? (What book do I buy to learn the theory?)

2) In quantitative investing circles, it is well known (and Eddy has written about it recently for us) that momentum works in the short run, and is often one of the most powerful return anomalies in the market. Is being a good technician just another way of trying to decide when to jump onto assets with positive price momentum for short periods of time? Can I equate technical analysis with buying momentum?

To any of you that answer, I thank you. If we get enough answers, maybe the editors will want to do a 360.

Position: none

I kinda thought this might happen, but I received zero public responses. I did receive one thoughtful private response, but I was asked to keep it private. Suffice it to say that some in TA think there is a difference between TA and chart-reading.

As for me, though I have sometimes been critical of TA, and sometimes less than cautious in my words, my guesses at the two questions are: 1) There is no common underlying theory to all TA, there are a variety of competing theories. 2) Most chart-readers are momentum players, as are most growth investors. Some TA practitioners do try to profit from turning points, but they seem to be a minority.

I’m not saying TA doesn’t work, because I have my own variations on it that I have applied mainly to bond investing. But I’m not sure how one would test if TA in general does or doesn’t work, because there may not be a commonly accepted definition of what TA would say on any specific situation.

4) One more note from RM today:

Um, after reading this article at the Financial Times, I thought it would be a good idea for me to point readers to my article that explained the 2005 Correlation Crisis. Odds are getting higher that we get a repeat. What would trigger the crisis? A rapid decline in creditworthiness for a minority of companies whose debts are referenced in the relevant credit indexes, while the rest of the companies have little decline in creditworthiness. One or two surprise defaults would really be gruesome.

Just something to watch out for, as if we don’t have enough going wrong in our debt markets now. I bumped into some my old RM articles and CC comments from 2005, and the problems that I described then are happening now.

Position: none, and there are times when I would prefer not being right. This is one of them. Few win in a bust.

There are situations that are micro-stable and macro-unstable, and await some force to come along and give it a push, knocking it out of its zone of micro-stability, and into a new regime of instability. When you write about situations like that before the fact, it is quite possible that you can end up wrong for a long time. I wrote for several years as RM about overleveraging credit, mis-hedging, yield-seeking, over-investment in residential real estate (May 2005), subprime lending (November 2006), quantitative strategies gone awry, etc. The important thing is not to put a time on the prediction because it gives a false message to readers. One can see the bubble forming, but figuring out when cash flow will be insufficient to keep the bubble financed is desperately hard.

5) This brings up another point. It’s not enough to know that an investment will eventually yield a certain outcome, for example, that a distressed tranche of an ABS deal will eventually pay off at par. One also has to understand whether an investor can handle the financing risks before receiving the eventual payoff. Will your prime broker continue to finance you on favorable terms? Will your regulator force you to put up more capital against the position? Will your investors hang around for the eventual payoff, or will they desert you, and turn you into a forced seller? Can your performance survive an asset that might be a dud for some time?

This is why the price path to the eventual payoff matters. It shakes out the weak holders, and moves assets that should be financed by equity onto strong balance sheets. It’s also a reason to be careful with your own balance sheet during boom times, and in the beginning and middle of financial crises — don’t overextend your positions, because you can’t tell how long or deep the crisis might be.

6) I agree with Caroline Baum; I don’t think that the FOMC is pushing on a string. The monetary aggregates are moving up, and nominal GDP will as well… it just takes time. The yield curve has enough slope to benefit banks that don’t face a lot of credit problems… and the yield curve will steepen further from here, particularly if the expected nadir of Fed funds drops below 2%. Now, will real GDP begin to pick up steam? Not sure, the real question is how much inflation the Fed is willing to accept in the short run as they try to reflate.

7) Now, inflation seems to be rising globally. At this point in the cycle, the FOMC is ahead of almost all major central banks in loosening policy. I think that is baked into the US dollar at present, so unless the FOMC gets even more ahead, the US Dollar should tread water here. Eventually inflation elsewhere will get imported into the US. It’s just a matter of time. That’s why I like TIPS here; eventually the level of inflation passing through the CPI will be reflected in implied inflation rates.

8 ) Okay, MBIA will split in 5 years? That is probably enough time to strike deals with most everyone that they wrote coverage for structured products, assuming the losses are not so severe that the entire holding company is imperiled. If it’s five years away, splitting is a possibility, but then are the rating agencies willing to wait that long? S&P showed that they are willing to wait today. Moody’s will probably go along, but for how long?

9) I found it interesting that AQR Capital has not been doing well in 2008. When quant funds did badly in the latter half of 2007, I suffered along with them. At present, I am certainly not suffering, but it seems that the quants are. I wonder what is different now? I suspect that there is too much money chasing the anomalies that the quant funds target, and we reached the end of the positive self-reinforcing cycle around mid-year 2007; since then, we have been in a negative self-reinforcing cycle, with clients pulling money, and the ability to carry positions shrinking.

10) Now some graphs tell a story. Sometimes the story is distorted. This graph of the spread on Fannie Mae MBS is an example. Not all of the spread is due to the creditworthiness of Fannie Mae. Those spreads have widened 30 basis points or so over the past six months for Fannie’s on-the-run 5-year corporate bond, versus 50 basis points on the graph that I referenced. So what’s the difference? Increased market volatility makes residential MBS buyers more skittish, and they demand a higher yield for bearing the negative optionality inherent in RMBS. Fannie and Freddie are facing harder times from the guarantees that they have written, and the credit difficulties at the mortgage insurers, but it would be difficult to imagine the US Government allowing Fannie or Freddie to default on senior obligations.

That’s another reason why I like agency-backed RMBS here. You’re getting paid a decent spread to bear the risks involved.

11) I would be cautious about using prics from CMBX, ABX, etc., to make judgments about the cash bonds that they reference. It is relatively difficult to borrow and short small ABS and CMBS tranches. It is comparatively easy to buy protection on the indexes, the only question is what level does it take to induce another market participant to sell protection to you. When there is a lot of pressure to short, prices overshoot on the downside, and stay well below where the cash bonds would trade.

12) One last point, this one coming via one of our dedicated readers passing on this blurb from David Rosenberg at Merrill Lynch:

A client sent this to us last week

It was a New York Times article by Louis Uchitelle in December 1990 on the housing and credit crunch. In the article, there is a quote that goes like this ? ?This is different from the experience of the Great Depression, but something related to the 1930?s is beginning to happen?. Guess who it was that said that (answer is at the bottom of the Tidbits).

Answer to question above

?Ben Bernanke, a Princeton University Economist? (and future Fed chairman, but who knew that then?).

My take: it is a very unusual time to have a man as Fed Chairman who is a wonk about the Great Depression. That makes him far more likely to ease. The real question is what the FOMC will do if economic weakness persists, and inflation continues to creep up. I know that they want to save the day, and then remove all policy accomodation, but that’s a pretty difficult trick to achieve. In this scenario, I don’t think the gambit will work; we will likely end up with a higher rate of price inflation.