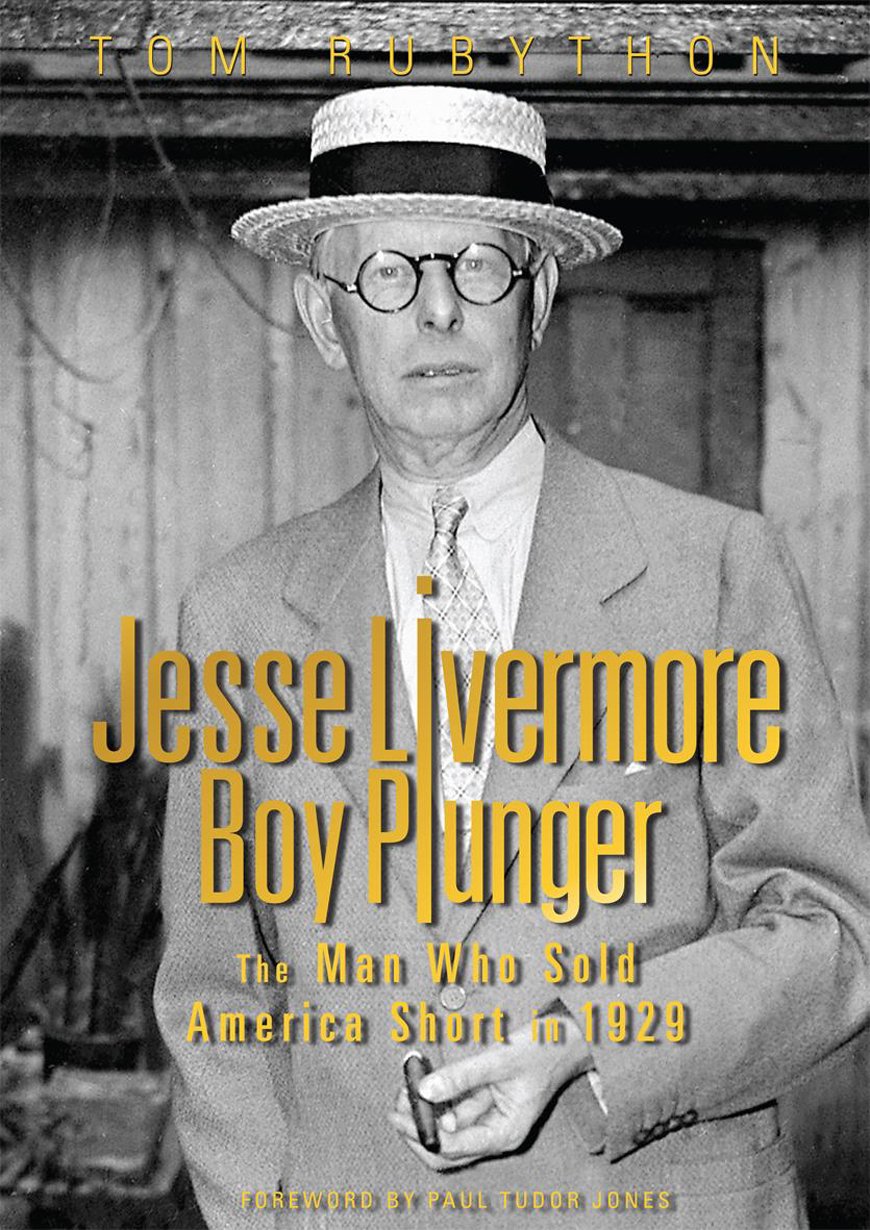

Book Review: Jesse Livermore: Boy Plunger

This is a story of triumph and tragedy. ?Jesse Livermore is notable as one of the few people who ever made it into the richest tiers of society by speculating — by trading stocks and commodities — betting on price movements.

This is three stories in one. ?Story one is the clever trader with an intuitive knack who learned to adapt when conditions changed, until the day came when it got too hard. ?Story two is the man who lacked financial risk control, and took big chances, a few of which worked out spectacularly, and a few of ruined him financially. ?Story three is how too much success, if not properly handled, can ruin a man, with lust, greed and pride leading to his death.

The author spends most of his time on story one, next most on story two, then the least on story?three. ?The three stories flow naturally from the narrative that is largely chronological. ?By the end of the book, you see Jesse Livermore — a guy who did amazing things, but?ultimately failed in money and life.

Let me briefly summarize those three aspects of his life so that you can get a feel for what you will run into in the book:

The Clever Trader

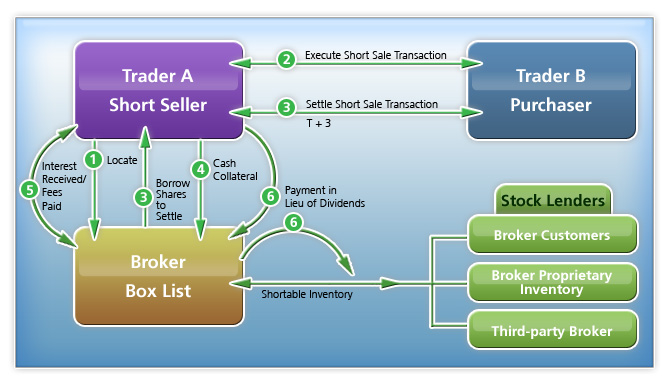

Jesse Livermore came to the stock market in Boston at age 14, and was a very quick study. ?He showed intuition on market affairs that impressed the most of the older men who came to trade at the brokerage where he worked. ?It wasn’t too long before he wanted to invest for himself, but he didn’t have enough money to open a brokerage account, so he went to a bucket shop. ?Bucket shops were gambling parlors where small players gambled on stock prices. ?He showed a knack for the game and made a lot of money. ?Like someone who beats the casinos in Vegas, the proprietors forced him to leave.

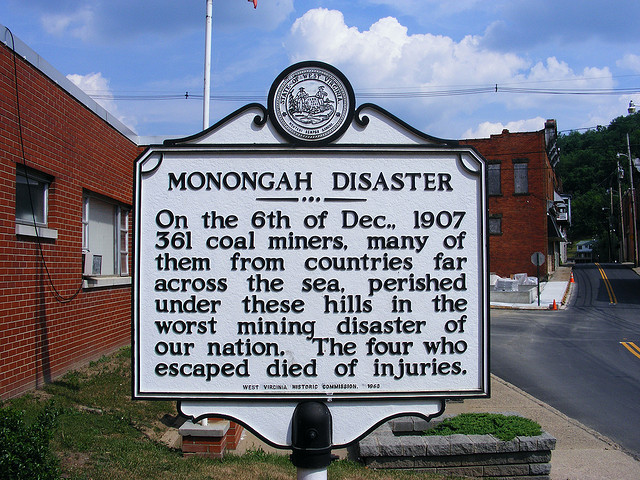

He then had more than enough money to meet his current needs, and set up a brokerage account. ?But the stock market did not behave like a bucket shop, and so he lost money while he learned to adapt. ?Eventually, he succeeded at speculating on both stocks and commodities, leading to his greatest successes in being short the stock market prior to the panic of 1907, and the crash in 1929. ?During the 1920s, he started his own firm to try to institutionalize his gifts, and it worked for much of the era.

After the crash in 1929, the creation of the SEC and all the associated laws and regulations made speculating a lot more difficult, to the point where he could not make significant money speculating anymore.

The Poor Financial Risk Manager

Amid the successes, he tended to aim for greater wins after his largest successes, which led to him losing much of what he had previously made. ?One time he was cheated out of much of what he had while trading cotton.

Amid all of that, he was well-liked by most he interacted with in a business context. ?Even after great losses, many wanted him to succeed again, and so they bankrolled him after failure. ?Before?the Great Depression, he did not disappoint them — he succeeded in speculation and came roaring back, repaying all of his past debts with interest.

In one sense, it was live by the big speculation, and?die by the big speculation. ?When you play with so much borrowed money, it’s hard for results to not be volatile.

A?Rock Star of His Era

When he won big, he lived big. ?Compared to many wealthy people of his era, he let spending expand far more than many who had ?more reliable sources of income. ?Where did the money go? ?Yachts, homes, staff, wives, women, women, women… ?Aside from the last of his three wives, his marriages were troubled.

His last wife was a nice woman who was independently wealthy, and after Livermore lost?it all in the mid-’30s, he increasingly relied on her to stay afloat. ?When he could no longer be the hero who could win a good living out of the market via speculation, his deflated pride led him to commit suicide in 1940.

A Sad Book Amid Amazing Successes

Sadly, his son and grandson who shared his name committed suicide in 1975 and 2006, respectively. ?On the whole, the story of Jesse Livermore’s?life and legacy is a sad one. ?It should disabuse people of the notion that wealth?brings happiness. ?If anything, it teaches that money that comes too easily tends to get lost easily also.

The author does a good job?weaving the strands of his life into a consistent whole. ?The book is well-written, and probably the best book out there on the life of the famous speculator that so many present speculators admire. ?A side benefit is that in passing, you will learn a lot about the development of the markets during a time when they were less regulated. ?(The volatility of markets was obvious then. ?It not obvious now, which is why people get surprised by it when it explodes.)

Quibbles

None.

Summary / Who Would Benefit from this Book

This is a comprehensive book that explains?the life and times of Jesse Livermore, one of the greatest speculators in history. ?It will teach you history, but it won’t teach you how to speculate. ?If you want to buy it, you can buy it here: Jesse Livermore – Boy Plunger: The Man Who Sold America Short in 1929.

Full disclosure:?I?received a?copy from a kind PR flack.

If you enter Amazon through my site, and you buy anything, I get a small commission.? This is my main source of blog revenue.? I prefer this to a ?tip jar? because I want you to get something you want, rather than merely giving me a tip.? Book reviews take time, particularly with the reading, which most book reviewers don?t do in full, and I typically do. (When I don?t, I mention that I scanned the book.? Also, I never use the data that the PR flacks send out.)

Most people buying at Amazon do not enter via a referring website.? Thus Amazon builds an extra 1-3% into the prices to all buyers to compensate for the commissions given to the minority that come through referring sites.? Whether you buy at Amazon directly or enter via my site, your prices don?t change.