When I was a Boy…

===========================================

If you knew me when I was young, you might not have liked me much. ?I was the know-it-all who talked a lot in the classroom, but was quieter outside of it. ?I loved learning. ?I mostly liked my teachers. ?I liked and I didn’t like my fellow students. ?If the option of being home schooled had been offered to me, I would have jumped at it in an instant, because then I could learn with no one slowing me down, and no kids picking on me.

I read a lot. A LOT. ?Even when young I spent my time on the adult side of the library. ?The librarians typically liked me, and helped me find stuff.

I became curious about investing for two reasons. 1) my mother did it, and it was difficult not to bump into it. ?She would watch Wall Street Week, and often, I would watch it with her. ?2) Relatives gave me gifts of stock, and my Mom taught me where to look up the price in the newspaper.

Now, if you knew the stocks that they gave me, you would wonder at how I still retained interest. ?The two were the conglomerate Litton Industries, and the home electronics company?Magnavox. ?Magnavox was bought out by Philips in 1974 for a price that was 25% of the original cost basis of my shares. ?We did worse on Litton. ?Bought in the mid-to-late ’60s and sold in the mid-’70s for a 80%+ loss. ?Don’t blame my mother for any of this, though. ?She rarely bought highfliers, and told me that she would have picked different stocks. ?Gifts are gifts, and I didn’t need the money as a kid, so it didn’t bother me much.

At the library, sometimes I would look through some of the research volumes that were there for stocks. ?There are a few things that stuck with me from that era.

1) All bonds traded at discounts. ?It’s not that I understood it well, but I remember looking at bond guides, and noted that none of the bonds traded over $100 — and not surprisingly, they all had low coupons.

In those days, some people owned individual bonds for income. ?I remember my Grandma on my mother’s side talking about how little one of her bonds paid in interest, given that inflation was perking up in the 1970s. ?Though I didn’t hear it in that era, bonds were sometimes called “certificates of confiscation” by professionals ?in the mid-to-late ’70s. ?My Grandpa on my father’s side thought he was clever investing in short-term CDs, but he never changed on that, and forever missed the rally in stocks and long bonds that kicked off in 1982.

When I became a professional bond investor at the ripe old age of 38 in 1998, it was the opposite — almost all bonds traded at premiums, and had relatively high coupons. ?Now, at that time I knew a few firms that were choking because they had a rule that said you can never buy premium bonds, because in a bankruptcy, the premium will be automatically lost. ?Any recoveries will be off the par value of the bond, which is usually $100.

2) Many stocks paid dividends that were higher than their earnings. ?I first noticed that while reading through Value Line, and wondered how that could be maintained. ?The phrase “borrowing the dividend” was bandied about.

Today as a professional I know that we should look at free cash flow as a limit for dividends (and today, buybacks, which were unusual to unheard of when I was a boy), but earnings still aren’t a bad initial proxy for dividend viability. ?Even if you don’t have a cash flow statement nearby, if debt is expanding and earnings don’t cover the dividend, I would be concerned enough to analyze the situation.

3) A lot of people were down on stocks and bonds — there was a kind of malaise, and it did not just emanate from Jimmy Carter’s mind. [Cue the sad Country Music] Some concluded that inflation hedges like homes, short CDs, and gold/silver were the only way to go. ?I remember meeting some goldbugs in 1982 just as the market was starting to take off, and they disdained the idea of stocks, saying that history was their proof.

The “Death of Equities” came and went, but that reminds me of one more thing:

4) There was a decent amount of pessimism about defined benefit plan pension funding levels and life insurer solvency. ?Inflation and high interest rates made life insurers look shaky if you marked the assets alone to market (the idea of marking liabilities to market was at least 10 years off in concept, and still hasn’t really arrived, though cash flow testing accomplishes most of the same things). ?Low stock and bond prices made pension plans look shaky. ?A few insurance companies experimented with buying gold and other commodities, just in time for the grand shift that started in 1982.

Takeaways

The biggest takeaway is to remember that as a fish you don’t notice the water that you swim in. ?We are so absorbed in the zeitgeist (Spirit of the Times)?that we usually miss that other eras are different. ?We miss the possibility of turning points. ?We miss the possibility of things that we would have not thought possible, like negative interest rates.

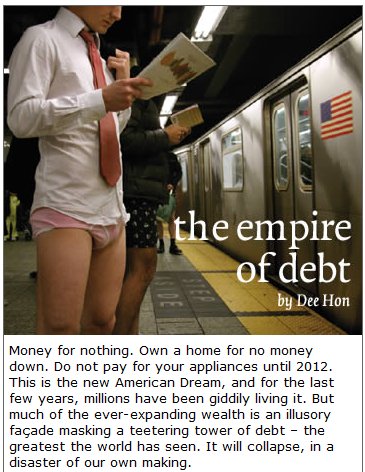

In the mid-2000s, few thought about the possibility of debt deflation having a serious impact on the US economy. ?Many still feared the return of inflation, though the peacetime inflation of the late ’60s through mid-’80s was historically unusual.

The Soviet Union will bury us.

Japan will bury us. ?(I’m listening to some Japanese rock as I write this.) 😉

China will bury us.

Few people can see past the zeitgeist. ?Many can’t remember the past.

Should we?be concerned about companies not being able pay their dividends and fulfill their buybacks? ?Yes, it’s worth analyzing.

Should we be concerned about defined benefit plan funding levels? Yes, even if interest rates rise, and percentage deficits narrow. ?Stocks will likely fall with bonds if real interest rates rise. ?And, interest rates may not rise much soon. ?Are you ready for both possibilities?

Average people don’t seem that excited about any asset class today. ?The stock market is at new highs, and there isn’t really a mania feel now. ?That said, the ’60s had their highfliers, and the P/Es eventually collapsed amid inflation and higher real interest rates. ?Those that held onto the Nifty Fifty may not have lost money, but few had the courage. ?Will there be a correction for the highfliers of this era, or, is it different this time?

It’s never different.

It’s always different.

Separating the transitory from the permanent is tough. ?I would be lying to you if I said I could do it consistently or easily, but I spend time thinking about it. ?As Buffett has said, (something like)?”We’re paid to think about things that can’t happen.

Ending Thoughts

Now, lest the above seem airy-fairy, here are my biases at present as I try to separate the transitory from the permanent:

- The US is in better shape than most of the rest of the world, but its securities are relatively priced for that reality.

- Before the US has problems, Japan, China, OPEC, and the EU will have problems, in about that order. ?Sovereign default used to be a large problem. ?It is a problem that is returning. ?As I have said before — this era reminds me of the 1840s — huge debts and deficits, with continued currency debasement. ?Hopefully we don’t get a lot of wars as they did in that decade.

- I am treating long duration bonds as a place to speculate — I’m dubious as to how much Trump can truly change things. ?I’m flat there now. ?I think you almost have to be a trend follower there.

- The yield curve will probably flatten quickly if the Fed tightens more than once more.

- The internet and global demographics are both forces for deflationary pressure. ?That said, virtually the whole world has overpromised to their older populations. ?How that gets solved without inflation or defaults is a tough problem.

- Stocks are somewhat overvalued, but the attitude isn’t frothy.

- DIvidend stocks are kind of a cult right now, and will suffer some significant setback, particularly if interest rates rise.

- Eventually emerging markets and their stocks will dominate over developed markets.

- Value investing will do relatively better than growth investing for a while.

That’s all for now. ?You may conclude very differently than I have, but I would encourage you to try to think about the hard problems of our world today in a systematic way. ?The past teaches us some things, but not enough, which should tell all of us to do risk control first, because you don’t know the future, and neither do I. 🙂