The Value of a CFA Charter: Ethics

Picture Credit: Marco Verch Professional Photographer || Being a financial analyst is being a competent generalist in business

Let me tell you why I am writing this, roughly three years later than I said I would. It started with a post I entitled Limits. The post itself is not why I am writing this, but in the the comments there was great criticism of the CFA Institute. They asked me what I thought of the criticisms and I said I would write about it.

I suspect no one will like this post. I will mention that I served on the board of the Baltimore CFA Society for 12 years, serving nine years as its Secretary, and two years as its programs chair. I am grateful that I earned my CFA credential in 1996, which enabled me to transition from being a life actuary, to being an investment actuary, to being a a financial analyst with actuarial skills.

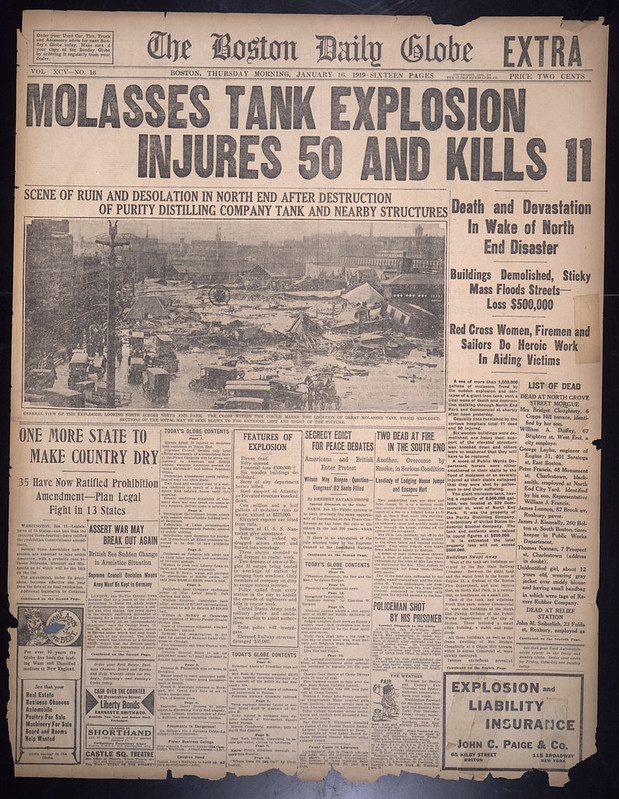

Four weeks ago, I gave a talk at the Baltimore CFA Society’s Charter Award Dinner. The title of the talk was “The Value of Ethics –The Value of a CFA Charter.” The main point of my talk was that the uniqueness of the CFA Charter did not stem from the “Body of Knowledge” imparted in the exams, but rather from the emphasis on ethics. The men who created the “National Federation of Financial Analysts Societies” in 1947 wanted financial analysts to be competent and ethical. After all, the Great Depression soured many people on investing, considering all of the unsavory tactics that many speculators used.

So what made me decide to write this tonight? My friend Tom Brakke made the following post at LinkedIn. He laments the decline in the teaching of the “Body of Knowledge” at the CFA Institute. I agree with him. The leadership of the CFA Institute seems weak to me, and gives in to political and cultural trends. Two examples: first, adding cryptocurrency to the “body of knowledge,” when it has no intrinsic value. Second, adding ESG to the body of knowledge, when it is ill-defined, useless, and not in the interests of those served by fiduciaries.

What should the CFA Institute do with respect to the “Body of Knowledge?” Investment knowledge is not a monopoly of the CFA Institute. You can get the same knowledge through many different sources. For me, I learned 90%+ of my investment knowledge before I took my first CFA exam. That’s why they were so easy for me. Many CFA Charterholders don’t like me saying the exams are easy, but I will say, “Have you taken an actuarial exam? There is no comparison.” Even the penultimate president of the CFA Institute said to me, “They have an amazing qualification process.” (Something like that…)

What should the CFA Institute do to create its “Body of Knowledge?” Choose the most compact and important knowledge that an intelligent investor needs to know, and then pursue it in a written exam format, not using computers. Why written? Because investing requires the ability to be able to write. The Society of Actuaries made a similar mistake when it eliminated their English exam, which turned their candidates into math nerds who often could not understand qualitative features in insurance. Actuaries once were CEOs of insurance companies, and that is rare now.

Does the CFA Institute’s Body of Knowledge need reform? Definitely. Clear out the crud, and make more room for the basics. Also, emphasize ethics, because that is what differentiates CFA Charterholders from other investment workers.

But Back to the Original Reason for Writing this

So what of people who pass the CFA exams, get a job, stop paying their CFA dues, and say that they passed the CFA exams, but not explicitly calling themselves CFA Charterholders? Are they cheating the system?

Yes, they are cheating the system, and if the CFA Institute had an ounce of courage, they would take them to court, saying that they agreed to the CFA Institute’s standards when they took the exams and received the Charter. If they are not doing so now, they can’t say they passed the exams. It might be true, but it is an obfuscation to have some benefit of a CFA Charter while not continuing to hold to its code of ethics. If you are not subject to the CFA Code of Ethics, you should not be allowed to mention that you were once a CFA.

The same is true for me. I never say that I am a Fellow in the Society of Actuaries, though I passed all of the exams and was inducted. I haven’t paid dues for over a decade, nor have I done their continuing education (that was the bigger issue). Do I still know their body of knowledge? I was a leader in asset-liability management inside life insurers, and I would still be a leader there.

To close this article, I would simply say to those who have dropped their CFA charters, but still try to benefit from them: pay the money and observe the code of ethics. Be a real CFA Charterholder. We are the ones that are supposed to be cleaning up the financial industry. This is our ethical obligation that you agreed to when you received your CFA Charter. Don’t be a cheapskate, and don’t be unethical by avoiding the duties that you accepted when you took the CFA exams.