Photo Credit: House Photography || I always read a lot when I was young

This a is follow-up to When I was a Boy… which I wrote ~5 1/2 years ago. It is also a response to an article posted by Jason Zweig, who I have talked with once or twice, and emailed a little more than that. In that article, he asks the question:

How did you learn how to invest? Did you take a class, play a stock-market game in school, have a friend or family member as a mentor?

How Should Kids Learn to Invest?

If you read the original article, you would know that my original start was from two gifts of stock that male relatives in my extended family gave me in the 1960s. They picked two high-fliers — Litton Industries and Magnavox. Bought and held, by the mid-1970s both generated >80% losses when they were bought by another company.

Did I ever play the stock market game in school? Yes, once when I was in seventh grade (early 1973). Our school decided to play around and do an intersession between the two semesters. It was a two week course called “Bulls and Bears. How this Little Piggy Went to Market.” My favorite science teacher was teaching it. I realized that the game was utterly short-term and so I put all of my play money into AT&T warrants, knowing that if AT&T stock rose, the warrants would zoom up. Was I a smart kid, or what?

What. Well, AT&T when nowhere for those two weeks, and the same for the warrants. They were at the same price at the contest end, thus losing the commissions on both sides, and this was when commissions were high, prior to deregulation.

The three main things that taught me about investing were watching Wall Street Week with my Mom, borrowing books on investing at the Brookfield library, and reading the Value Line subscription that she purchased.

I probably read 10 books on investing before I was 18. Louis Rukeyser was an affable guide to the markets, including the elves, the guests, etc. (As an aside, Frank A. Cappiello, Jr. was a founding member of the Baltimore Security Analysts Society, and a frequent guest on his show. After all, where is Owings Mills, Maryland?)

With Value Line, I began to understand how corporations worked. The one-page descriptions of companies were just big enough to give me a good idea of what was going on, while not over-taxing a kid 12-21 years old.

I remember as a student at Johns Hopkins earning 16% on my money market fund in my freshman year. I was only at Hopkins for three years 1979-1982, but those were tough years, particularly in the Midwest “Rust Belt.” My father’s business earned little, but my Mom’s investing paid off. Though not “working” she was making more off the family portfolio than my Dad was earning off his business. As it was, to help my family then, I paid the last semester of tuition. (My Mom later paid me back for that.) I came back home in 1982 with $5 in my pocket. Then I learned that I overdrew my bank account, costing me $10.

Oh, one more thing the clever and distinguished Carl Christ, who signed my Master’s Thesis at Hopkins, taught a class on investing in my junior year. I learned a lot, but the main thing I remember was writing a research report on a firm that made specialty paper — James River. My mother had owned it for a long time, but had sold her stake at an opportune time. When I wrote the report, she did not own it, and the stock had fallen from where she sold it. Dr. Christ had never heard of James River, an was fascinated at what was at that time a midcap firm in a underfollowed industry. I got an “A.” When I showed the report to my Mom, she bought it again, and made money of it.

Also, in my senior year, I wrote my thesis on stock splits. As I said there:

This brings me to my conclusion: stock splits are a momentum effect, but it is larger when companies are still have a cheap valuation. Perhaps splits have no effect on stock performance — it is all momentum and valuation. To me, that is the most likely conclusion, and my thesis anticipated quantitative money management by 10+ years.

On Stock Splits

In the summer of 1982, I remember sitting down with Value Line in my family’s living room (quiet place, no TV) and selecting a paper portfolio of 40-50 stocks. I went through all 1700 stocks. I recorded the prices in the Milwaukee Journal, and then went to Grad School at UC-Davis. Over the next year the stocks in my “portfolio” appreciated at double the rate of the market. At that time, I was a TA for a Corporate Financial Management class. I showed it to the professor, and he said, “Oh, you have a beta of two.” I said, “No, this portfolio has stocks that are not as risky as the market. This is alpha, not beta.”

Several years later, I participated in the Value Line Investing Contest. I placed in the top 1%, but not good enough to win.

When my dissertation committee dissolved, I was forced to abandon my Ph. D. I took three actuarial exams on the fly in early 1986 and passed. I had an informational interview at Pacific Standard Life which sponsored the exams, and they hired me on the spot. (My boss’ secretary told me that the boss said, “No one can pass the first three exams on the first try.” Then a fellow employee told me later, “You didn’t negotiate hard enough. They would have hired you regardless.”)

When I worked for Pacific Standard Life, and later AIG, I got investment-related projects, because I was the one actuary that understood investing. During this time, I was managing my own portfolio, sometimes better, sometimes worse. I bought stocks, and mutual funds investing outside the US. I had a CTA in my portfolio. I tried investing in spectrum with the FCC, but that was a bomb. I settled on small cap value investing in the mid-1990s, which was a bad era for small cap value. Still, I managed to keep pace with the S&P 500.

In 2000, I had an email exchange with Kenneth Fisher (yes, the big guy of Fisher Investments). This led to he creation of my eight rules. As I wrote on portfolio rule three:

Let me give you a little history of how the eight rules came to be. In 2000, I had an e-mail discussion with Kenneth Fisher. I explained to him what I had been doing with small-cap value, and how I had done well with it in the 90s. He told me to forget everything that I’ve learned, especially the CFA syllabus, and look for the things that I can do better than anyone else. We exchanged about five or so e-mails; I appreciate the time he spent on me.

So I sat back and thought about what investments had worked best for me in the past. I noticed that when I got the call right on cyclical industries, the results were spectacular. I also noticed that I lost most when investing in companies that didn’t have good balance sheets, no matter how “cheap” they were in terms of valuation.

I came to the conclusion that size and value/growth were not the major determinants of my investing success. Instead, industry selection played a large role in what went right and wrong with my investment decisions. So, I decided to formalize that. I would rotate industries with a value bias. But that would have other impacts on how I invested. One of those impacts is rule number three.

Over the next ten years, I tore up the pavement, and would have been in the top percentile of mutual fund managers. And so I opened my own shop in 2010, to find for the next eleven years that value investing was overrated.

My life is bigger than my little company. I am a happy man. I know Jesus Christ; I have eternal life. Have there been disappointments? Of course. The one main positive I can say about my investing is that I rarely have big losses on any security. This is not due to stop losses; I pay attention to balance sheets and the cyclicality of markets.

Even at the age of 61, I am still learning. I am not a boy, obviously, but I am still absorbing new ideas. To all who read me, be life-long learners. I am closer to the end to my life than my beginning, but invest! Take your opportunities to learn and capitalize on them!

And remember, Judgement Day is coming. Are you ready? Investments will help you for now, but will be useless in the hereafter.

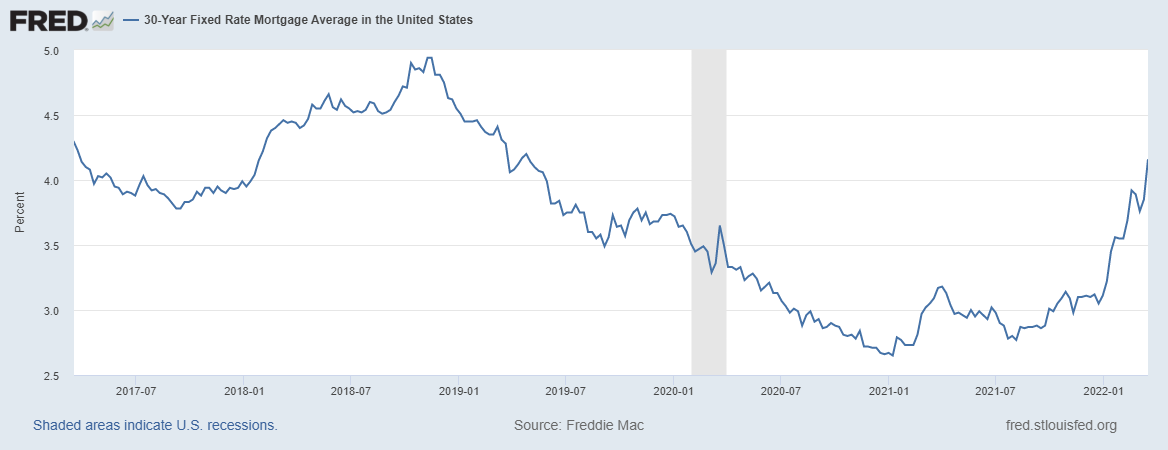

![Welcome Back to 1994! [Redux]](https://alephblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/mortgage-rates.png)