On the VAERS Database

Photo Credit: duncan c || I know it is graffiti, but face it, most arguments regarding COVID-19 or politics are little better than graffiti

There’s a popular argument going around about the VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System] database that the COVID-19 [C19] vaccines are killing a lot of people. I am here tonight to tell you that is likely false, but at minimum, that you can’t prove that through the VAERS database.

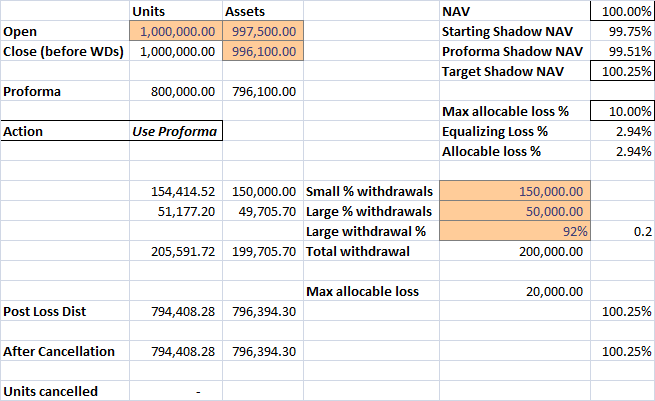

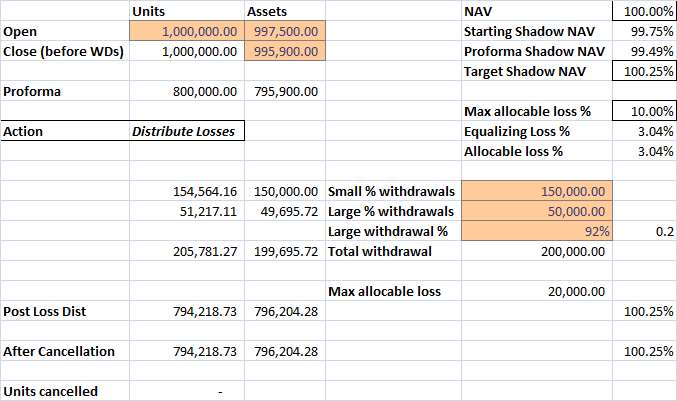

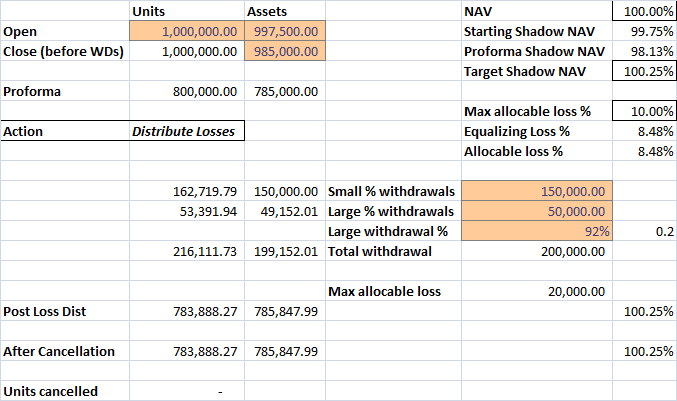

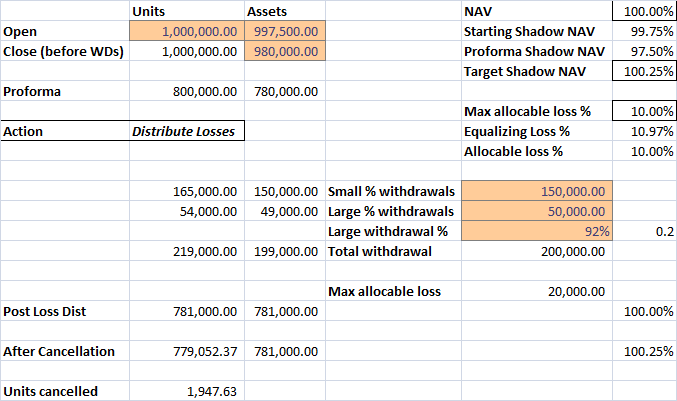

First a digression: Out of group of one million picked at random in the US, how many people will die on a given day?? Using 2019 US crude mortality data, roughly 20.?

So, out of 470 million vaccine doses administered, how many should have died for any reason within one day of receiving the dose of vaccine? Roughly 9,400.? Within two days? 18,800. How many deaths are in VAERS after one day? 1,921. Two days? 2,415. Expected deaths for any reason versus VAERS data after five days? 47,000 vs 3,244. Fourteen days? 131,600 vs 4,458. 30 days? 282,000 vs 5,629. There are 4,799 additional deaths 31 days and after, and those where no date was specified in the VAERS data. So, 10,428 deaths from COVID in the VAERS database.

So, the VAERS data does not support the idea that the vaccine is killing people.? Now the VAERS database has inconsistent and uncontrolled reporting ? it is a voluntary database, and anyone can post to it, makes any study design pretty useless, which is part of their disclaimers. Many allege underreporting but ask yourself “Could there be more than 25 deaths from the vaccines for every one reported?” Really, I doubt it. A big blip in the death rate from vaccination would get noticed ? you couldn?t suppress it. The news outlets would be all over the story.

We have never had a vaccination campaign of this size in the US before.? We should expect people dying post-vaccination at an ordinary rate.? Where VAERS could be useful would be looking at cause of death codes for a given vaccine, and seeing if there are any death causes that are unusual in proportion.? And that?s what the researchers mostly use the VAERS database for.

From other statistical work I have done I can tell you that the vaccines are generally effective, and that if you don’t have a medical reason to not get vaccinated, you should get vaccinated. The vaccines reduce the likelihood of infection, severity of infection, and the likelihood of death from C19.

And for my Christian friends who object because fetal tissue from abortions long ago were used in the process of creating the vaccines, I will ask you this: many drugs get tested or developed using the aborted fetal tissue, including aspirin, Tylenol, Ibuprofen, Lidocaine, Mucinex, Pepto Bismol, MMR Vaccine, Remdesivir, Tums, Maalox, Preparation H, Claritin, Robitussin, Lipitor, Zoloft, Aleve, Ex-Lax, Benadryl, Suphedrine, and Sudafed, among many others. Are you willing to make the moral claim and do without almost all drugs, not just the C19 vaccines?

Those children are dead, and nothing can be done about it. The cells that comprised their bodies are long since gone. The cells existing today are many generations removed from the babies who were killed through the abortions. Not that they should have been killed (let’s end Roe v Wade), but they have indirectly done more good for mankind than most people (including me) will ever do.

Public health is a proper province of government, unlike most matters that governments concern themselves with today, because it involves matters in health that can be made better via collective action. The Mosaic Law supports this idea. And so I say to my Christian friends, get vaccinated, and stop listening to the right wing media that milks you to make money via advertising.