A Cautionary Tale on Municipal Pensions

========================================================

If you want a full view of what I am writing about today, look at this article from The Post and Courier, “South Carolina’s looming pension crisis.” ?I want to give you some perspective on this, so that you can understand better what went wrong, and what is likely to go wrong in the future.

Before I start, remember that the rich get richer, and the poor poorer even among states. ?Unlike what many will tell you though, it is not any conspiracy. ?It happens for very natural reasons that are endemic in human behavior. ?The so-called experts in this story are not truly experts, but sourcerer’s apprentices who know a few tricks, but don’t truly understand pensions and investing. ?And from what little I can tell from here, they still haven’t learned. ?I would fire them all, and replace all of the boards in question, and turn the politicians who are responsible out of office. ?Let the people of South Carolina figure out what they must do here — I’m a foreigner to them, but they might want to hear my opinion.

Let’s start here with:

Central Error 1: Chasing the Markets

Much as inexperienced individuals did, the South Carolina?Retirement System Investment Commission [SCRSIC] chased the markets in an effort to earn returns when they seemed easy to get in hindsight. ?As the article said:

It used to be different, before the high-octane investment strategies began. South Carolina?s pension plans were considered 99 percent funded in 1999, and on track to pay all promised benefits for decades to come.

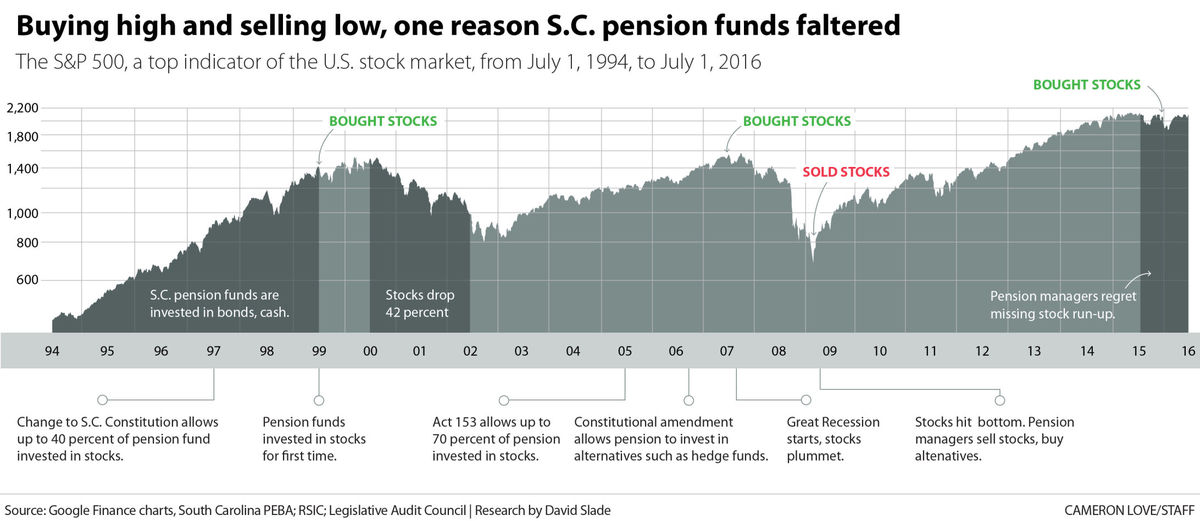

That was the year the pension funds started investing in stocks, in hopes of pulling in even more income. A change to the state constitution and action by the General Assembly allowed those investments. In the previous five years, U.S. stock prices had nearly tripled.

Prior to that time, the pension funds were largely invested in bonds and cash, which actually yielded something back then. ?If the pension funds were invested in bonds that were long, the returns might not have been so bad versus stocks. ?But in the late ’90s the market went up aggressively, and the money looked easy, and it was easy, partly due to loose monetary policy, and a mania in technology and internet stocks.

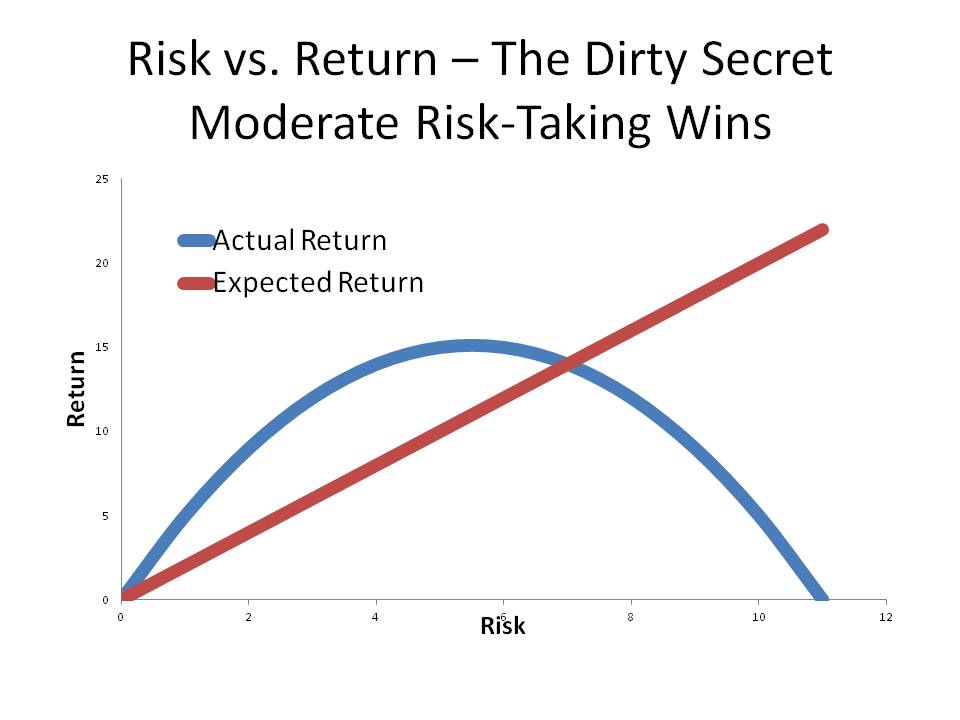

Here’s the real problem. ?It’s okay to invest in only bonds. It’s okay to invest in bonds and stocks in a fixed proportion. ?It’s okay even to invest only in stocks. ?Whatever you do, keep the same policy over the long haul, and don’t adjust it. ?Also, the more nonguaranteed your investments become (anything but high quality bonds), the larger your provision against bear markets must become.

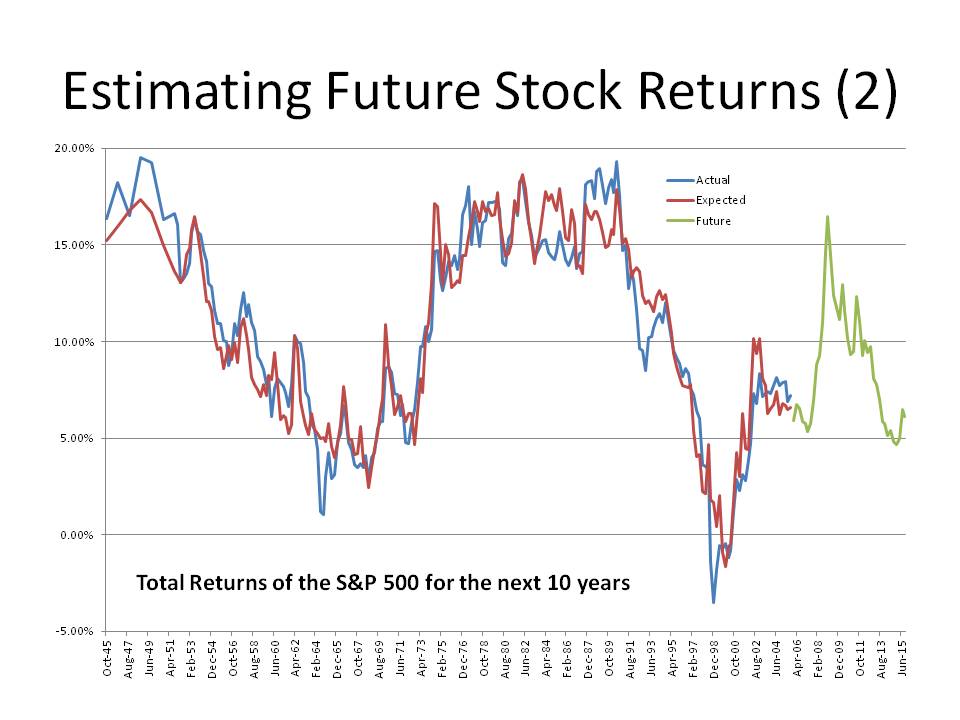

And, when you start a new policy, do what is not greedy. ?1999-2000 was the right time to buy long bonds and sell stocks, and I did that for a small trust that I managed at the time. ?It looked dumb on current performance, but if you look at investing as a business asking what level of surplus?cash flows the underlying investments will throw off, it was an easy choice, because bonds were offering a much higher future yield than stocks. ?But the natural tendency is to chase returns, because most people don’t think, they imitate. ?And that was true for the SCRSIC,?bigtime.

Central Error 2:?Bad Data

The above quote said that “South Carolina?s pension plans were considered 99 percent funded in 1999.” ?That was during an era when government accounting standards were weak. ?The?standards are still weak, but they are stronger than they were. ?South Carolina was NOT 99% funded in 1999 — I don’t know what the right answer would have been, but it would have been considerably lower, like 80% or so.

Central Error 3: Unintelligent Diversification into “Alternatives”

In 2009, I had the fun of writing a small report for CALPERS. ?One of my main points was that they allocated money to alternative investments too late. ?With all new classes of investments the best deals get done early, and as more money flows into the new class returns surge because the flood of buyers drives prices up. ?Pricing is relatively undifferentiated, because experience is early, and there have been few failures. ?After significant failures happen, differentiation occurs, and players realize that there are sponsors with genuine skill, and “also rans.” ?Those with genuine skill also limit the amount of money they manage, because they know that good-returning ideas are hard to come by.

The second aspect of this foolishness comes from the consultants who use historical statistics and put them into brain-dead mean-variance models which spit out an asset allocation. ?Good asset allocation work comes from analyzing what economic return the underlying business activities will throw off, and adjusting for risk qualitatively. ?Then allocate funds assuming they will never be able to trade something once bought. ?Maybe you will be able to?trade, but never assume there will be future liquidity.

The article kvetches about the expenses, which are bad, but the strategy is worse. ?The returns from all of the non-standard investments were poor, and so was their timing — why invest in something not geared much to stock returns when the market is at low valuations? ?This is the same as the timing problem in point one.

Alternatives might make sense at market peaks, or providing liquidity in distressed situations, but for the most part they are as saturated now as public market investments, but with more expenses and less liquidity.

Central Error 4: Caring about 7.5% rather than doing your best

Part of the justification for buying the alternatives rather than stocks and bonds is that you have more of a chance of beating the target return of the plan, which in this case was 7.5%/yr. ?Far better to go for the best risk-adjusted return, and tell the State of South Carolina to pony up to meet the promises that their forbears made. ?That brings us to:

Central Error 5: Foolish politicians who would not allocate more money to pensions, and who gave?pension increases rather than wage hikes

The biggest error belongs to the politicians and bureaucrats who voted for and negotiated higher pension promises instead of higher wages. ?The cowards wanted to hand over an economic benefit without raising taxes, because the rise in pension benefits does not have any immediate cash outlay if one can bend the will of the actuary to assume that there will be even higher investment earnings in the future to make up the additional benefits.

[Which brings me to a related pet peeve. ?The original framers of the pension accounting rules assumed that everyone would be angels, and so they left a lot of flexibility in the accounting rules to encourage the creation of defined benefit plans, expecting that men of good will would go out of their way to fund them fully and soon.

The last 30 years have taught us that plan sponsors are nothing like angels, playing for their own advantage, with the IRS doing its bit to keep corporate plans from being fully funded so that taxes will be higher. ?It would have been far better to not let defined benefit plans assume any rate of return greater than the rate on Treasuries that would mimic their liability profile, and require immediate relatively quick funding of deficits. ?Then if plans outperform Treasuries, they can reduce their contributions by that much.]

Error 5 is likely the biggest error, and will lead to most of the tax increases of the future in many states and municipalities.

Central Error 6: Insufficient Investment Expertise

Those in charge of making the investment decisions proved themselves to be as bad as amateurs, and worse. ?As one of my brighter friends at RealMoney, Howard Simons, used to say (something like), “On Wall Street, to those that are expert, we give them super-advanced tools that they can use to destroy themselves.” ? The trustees of?SCRSIC received those tools and allowed themselves to be swayed by those who said these magic strategies will work, possibly without doing any analysis to challenge the strategies that would enrich many third parties. ?Always distrust those receiving commissions.

Central Error 7: Intergenerational Equity of Employee Contributions

The last problem is that the wrong people will bear the brunt of the problems created. ?Those that received the benefit of services from those expecting pensions will not be the prime taxpayers to pay those pensions. ?Rather, it will be their children paying for the sins of the parents who voted foolish people into office who voted for the good of current taxpayers, and against the good of future taxpayers. ?Thank you, Silent Generation and Baby Boomers, you really sank things for Generation X, the Millennials, and those who will follow.

Conclusion

Could this have been done worse? ?Well, there is Illinois and Kentucky. ?Puerto Rico also. ?Many cities are in similar straits — Chicago, Detroit, Dallas, and more.

Take note of the situation in your state and city, and if the problem is big enough, you might consider moving sooner rather than later. ?Those that move soonest will do best selling at?higher real estate prices, and not suffer the soaring taxes and likely?diminution of city services. ?Don’t kid yourself by thinking that everyone will stay there, that there will be a bailout, etc. ?Maybe clever ways will be found to default on pensions (often constitutionally guaranteed, but politicians don’t always honor Constitutions) and municipal obligations.

Forewarned is forearmed. ?South Carolina is a harbinger of future problems, in their case made worse by opportunists who sold the idea of high-yielding investments to trustees that proved to be a bunch of rubes. ?But the high returns were only needed because of the overly high promises made to state employees, and the unwillingness to levy taxes sufficient to fund them.

[bctt tweet=”Seven central errors committed by the South Carolina Retirement System and politicians” username=”alephblog”]