Retirement ? A Luxury Good

Recently I was approached by Moneytips to ask my opinions about retirement. They sent me a long survey of which I picked a number of questions to answer. You can get the benefits of the efforts of those writing on this topic today in a free e-book, which is located here: http://www.moneytips.com/retiree-next-door-ebook.??The eBook will be available free of charge?through September 30th. ?I have a few quotes in the eBook.

Before I move onto the answers, I would like to share with you an overview regarding retirement, and why current and future generations are unlikely to enjoy it to the degree that the generations prior to the Baby Boomers did.

The first thing to remember is that retirement is a modern concept. That the world existed without retirement for over 5000 years may mean that it is not a necessary institution. For a detailed comment on this, please consult my article, “The Retirement Tripod: Ancient and Modern.” Here’s a quick summary:

In the old days, when people got old, they worked a reduced pace. They relied on their children to help them. Finally, they relied on savings.

Savings is the difficult concept. How does one save, such that what is set aside retains its value, or even grows in value?

If you go backwards 150 years or further in time, there weren’t that many ways to save. You could set aside precious metals, at the risk of them being stolen. You could also invest in land, farm animals, and tools, each of which would be the degree of maintenance and protection in order to retain their value. To the extent that businesses existed, they were highly personal and difficult to realize value from in a sale. Most businesses and farms were passed on to their children, or dissolved at the death of the proprietor.

In the modern world we have more options for when we get old ? at least, it seems like we have more options. In retirement, we have three ways to support ourselves: we have government security programs, corporate security programs, and personal savings.

Quoting from an earlier article of mine, Many Will Not Retire; What About You?:

Think of this a different way, and ignore markets for a moment.? How do we take care of those that do not work in society?? Resources must be diverted from those that do work, directly or indirectly, or, we don?t take care of some that do not work.

Back to?markets: Social Security derives its ways of supporting those that no longer work from the wages of those that do work.? That?s one reason to watch the ratio of workers to retired.? When that ratio gets too low, the system won?t work, no matter what.? The same applies to Medicare.? With a population where growth is slowing, the ratio will get lower. If the working population is shrinking, there is no way that benefits for those retiring will be maintained.

Pensions tap a different sort of funding.? They tap the profit and debt servicing streams of corporations and other entities.? Indirectly, they sometimes tap the taxpayer, because of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, which guarantees defined benefit pensions up to a limit.? There is no explicit taxpayer backstop, but in this era of bailouts, who can tell what will be guaranteed by the government in a crisis?

That said, not many people today have access to Defined-Benefit pensions. Those are typically the province of government workers and well-funded corporations. That leaves savings as the major way that most people fund retirement aside from Social Security.

One of the reasons why the present generations are less secure than prior generations with respect retirement is that the forebears who originally set up defined-benefit pensions and Social Security system set up in such a way that they gave benefits that were too generous to early participants, defrauding those who would come later. Though the baby boomers are not blameless here, it is their parents that are the most blameworthy. If I could go back in time and set things right, I would’ve set the defined-benefit pension funding rules to set aside considerably more assets so that funding levels would’ve been adequate, and not subject to termination as the labor force aged.

I also would’ve required the US government to set benefits at a level equal to that contributed by each generation, and given no subsidy to the generations at the beginning of the system. Truth, I would eliminate the Social Security system and Medicare if I could. I think it is a bad idea to have collective support programs. There are many reasons for that, but a leading reason is that it removes the incentive to marry and have children. Another reason is that it politicizes generational affairs, which will become obvious to the average US citizen over the next 10 to 15 years.

Back to Savings

As for personal savings today we have more options than our great-great-great-grandparents did 150 years ago. We can still buy land and we can still store precious metals ? both of those have a great ability to retain value. But, we can buy shares in businesses and we can buy the debt claims of others. We can also build businesses which we can sell to other people in order to fund our retirement.

But investing is tricky. With respect to lending, default is a significant risk. Also, at the end of the term of lending, what will the money be worth? We have to be aware of the risks of inflation and deflation.

In evaluating businesses more generally, it is difficult to determine what is a fair price to pay. In a time of technological change, what businesses will survive? Will the business managers be clever enough to make the right changes such that the business thrives?

You have an advantage that your parents did not have, though. You can invest in the average business and debt of public companies in the US, and around the world through index funds. This is not foolproof; in fact, this is a pretty new idea that has not been tested out. But at least this offers the capability of opening a fraction of the productive assets in our world, diversified in such a way that it would be difficult that you end up with nothing, unless the governments of the world steal from the custodians of the assets.

With that, I leave you to read my answers to some of the questions that were posed to me regarding retirement:

What is a safe withdrawal rate?

A safe withdrawal rate is the lesser of the yield on the 10 year treasury +1%, or 7%. The long-term increase in value of assets is roughly proportional to something a little higher than where the US government can borrow for 10 years. That’s the reason for the formula. Capping it at 7% is there because if rates get really high, people feel uncomfortable taking so much from their assets when their present value is diminished.

How should you handle a significant financial windfall?

If you have debt, and that debt is at interest rates higher than the 10 year treasury yield +2%, you should use the windfall to reduce your debt. If the windfall is still greater than that, treat it as an endowment fund, invest it wisely, and only take money out via the safe withdrawal rate formula.

What are some ways to learn to embrace frugality?

This is a question of the heart. You have to master your desires to have goods and services today that are discretionary in nature. Life is not about happiness in the short term but happiness and long-term. Embrace the concept of deferred gratification that your great-grandparents did and recognize that work and savings provide for a secure and happy future.

How can the average worker start earning passive income?

Passive income is a shibboleth. People look at that as a substitute for investing, because they can’t control investment returns, and they think they can control income.

Income comes from debt or a business. If from debt, it is subject to prepayment or default; it is not certain. Also, income that comes from debt is typically fixed. That income may be sufficient today, but it may not be so if inflation rises. Also your capital is tied up until the debt matures. When the debt matures, reinvestment opportunities may be better or worse than they were when you started.

If income comes from a business, it is subject to all the randomness of that business; it is not certain. It is subject to all of the same problems that an investment in the stock market is subject to, except that you have to oversee the business.

There is no such thing as a truly passive income. Get used to the fact that you will be investing and working to earn an income.

What can those workers who are not employed by a large company or the public sector do to maximize their retirement savings?

You can start an IRA. Until the rules change, you can create healthcare savings account, not use it, and let it accrue tax-free until you’re 59 1/2. Oh, you get an immediate income deduction for that too.

If you are a little more enterprising, you can start your own business. If your business succeeds, there are a lot of ways to put together a pension, deferring more income than an individual can. By the time you get there, the rules will have changed, so I won’t tell you how to do it today; at the time, get a good pension consultant.

Why is calculating how much you’ll need for retirement an important exercise?

You have to understand that retirement is a new concept. In the ancient world, retirement meant continued work at a slower pace on your farm, living off of savings (what little was storable then ? gold, silver, etc.), and help from your children whom you helped previously as you raised them.

Today’s society is far more personal, far less family centered, and far more reliant on corporate and governmental structures. Few of us produce most of the goods and services that we need. We rely on the division of labor to do this.? Older people will still rely on younger people to deliver goods and services, as the older people hand over their accumulated assets in exchange for that.

Practically, modern retirement is an exercise in compromise. You will have to trade off:

- How long you will work

- At what you will work

- What corporate and governmental income plans you participate in

- How much income with safety your assets can deliver, with an allowance for inflation

- How much you will help your children

- How much your children will help you

As such, calculating a simple figure how much your assets should be may be useful, but that one variable is not enough to help you figure out how you should conduct your retirement.

Why don’t more people consult investment professionals? What keeps them from doing so?

There are two reasons: first, most people don’t have enough income or assets for investment professionals to have value to them. Second, people don’t understand what investment professionals can do for them, which is:

- They can keep you from panicking or getting greedy

- They can find ways to reduce your tax burdens

- They can diversify your assets so that you are less subject to large drawdowns in the value of your assets

Other than maximizing your annual contribution, what other things can you do to get the most out of your IRA and 401(k)?

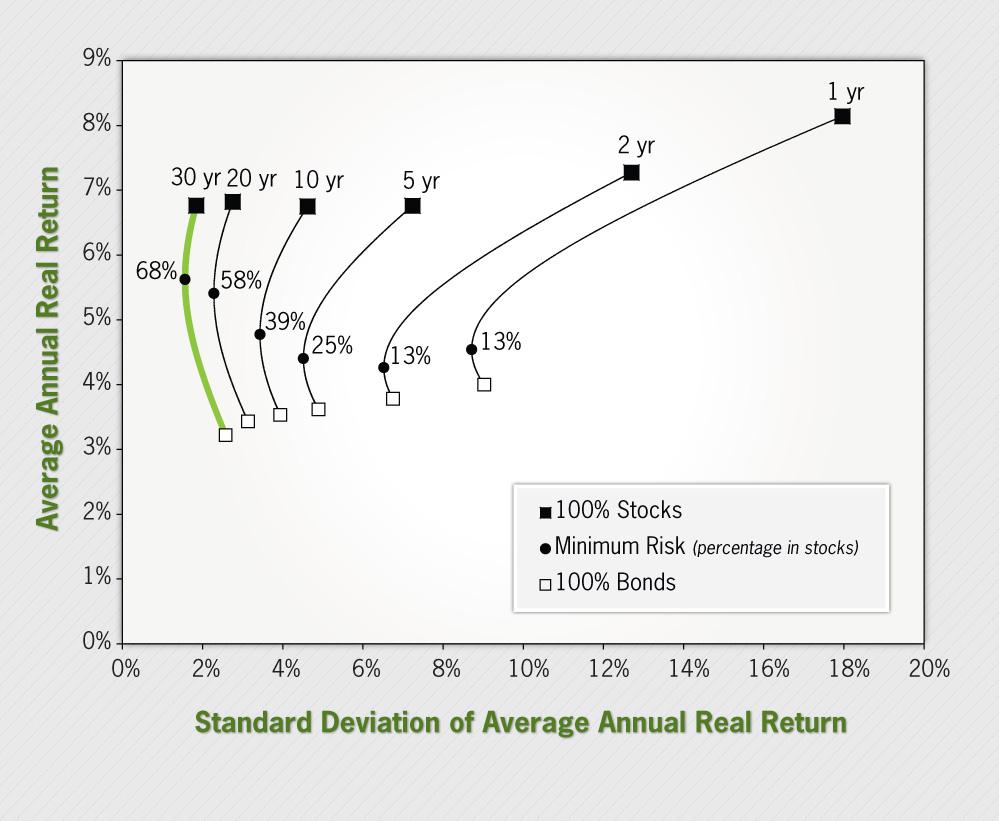

Diversify your investments into safe and risky buckets. The safe bucket should contain high quality bonds. The risky bucket should contain stocks, tilted toward value investing, and smaller stocks. New contributions should mostly feed investments that have been doing less well, because investments tend to mean-revert.

Stocks are clearly risky and investors have emotional reactions to that. How can investors rationally manage their stock investments so that they are less likely to regret their decisions?

When I was a young investor, I had to learn not to panic. I also had to learn not to get greedy. That means tuning out the news, and focusing on the long run. That may mean not looking at your financial statements so frequently.

As for me as a financial professional, I look at the assets that I manage for my clients and me every day, but I have rules that limit trading. I do almost all trading once per quarter, at mid-quarter, when the market tends to be sleepy, and not a lot of news is coming out. When I trade, I am making business decisions that reflect my long-term estimates of business prospects.

Closing

And if that is not enough for you, please consult my piece The Retirement Bubble. ?You can retire if you put enough away for it, but it is an awful lot of money given that present investments yield so little.