Picture Credit: Wiley Publishing || Ah, the golden umbrella!

This is a tough book to review. I don’t like the writing style — it is pompous, and drags you through a variety of “rabbit trails” that aren’t necessary to the core ideas of the book. Simplicity is beauty, so going on a travelogue of your philosophical interests detracts from the presentation of this book. As I have often said, the book needed a better editor who could overrule the author and say “That’s not relevant.” “That’s boring.” “Get to the point.” and “This is thin gruel.”

Quoting from pages 4-5:

‘As this book is, in part, a response to those questions, I do want to ensure that expectations are set appropriately at the start. This is not a “how-to” book, but it is a “why-to” as well as a “why-not-to” book. Let’s be clear: What I do specifically as a safe haven investor is not to be attempted by nonprofessionals (nor-perhaps even especially-by most professionals). Nothing that I could tell you in a book will change that.

So, I will not be holding your hand and teaching you how to do it; I will not be revealing much in the way of trade secrets, and I have no interest in selling you anything as an investment manager. This book is not about the workings of a specific safe haven strategy, per se; nor is it an encyclopedic survey of all the major safe haven investments. Moreover, it has little if any current market commentary-as this would be entirely unnecessary to the book’s point.‘

As such, the author talks in generalities, and does not give away his strategy. Do I blame him? No. I don’t blame him for not giving away his strategies. I do blame him for writing this book. Better to not write a vague book that is of no practical use to most who read it.

Modeling Issues

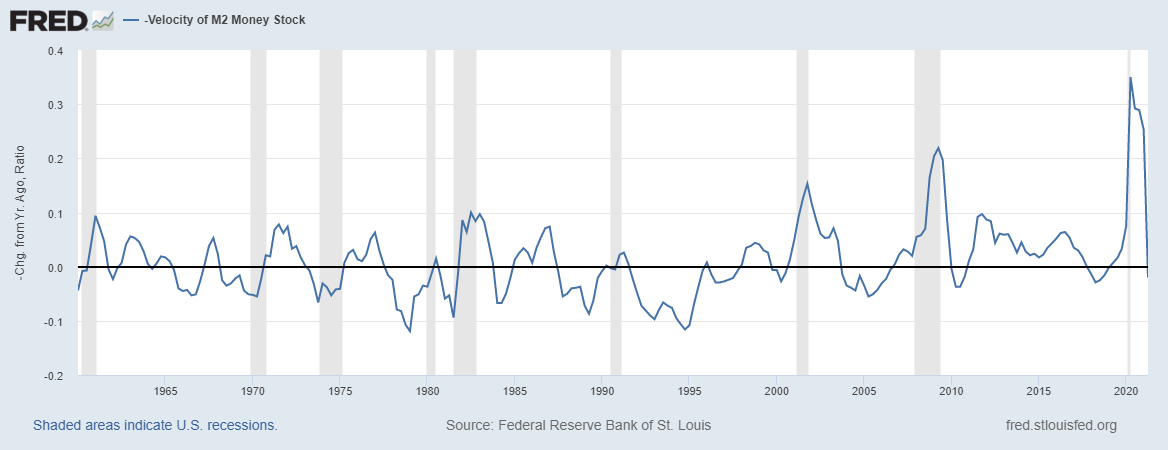

Then there are the modeling issues — a decent part of the book assumes that yearly returns are essentially random. Market returns are regime-dependent. There is momentum. There is weak mean reversion. The results in prior years affect the current year, both positively and negatively.

Toward the end of his analysis the author recognizes the problem and then uses 25-year blocks of S&P 500 returns 1900-2019 (or so), without noting that it gives undue weight to the years in the middle that get oversampled.

The grand problem is that we only have one history — and is it normal or an accident? We assume normal, but how can we know? Also, though we have 120 or so reliable years of performance for the pseudo-S&P 500, for options on the S&P 500, we only have ~35 years of data. For more esoteric diversifying investments, we have 10-40 years of data. We have no strong data on how they might have performed prior to their inception. Also, their modern presence may have affected the performance of the S&P 500.

Simulation analyses have to be done ultra-carefully. It’s best to develop an integrated structural model, deciding what variables are random and how they correlate with each other. Then use pseudo-random multivariate values for the analysis. I used these to great value to my employers 1996-2003 when I was an investment actuary.

What I Liked

But I like the book in some ways. He makes the important point that hedging when the cost of the hedge is fair or even in your favor is an advantage. And this is well known by regulated financial companies. There are two ways to win. 1) Source liabilities at favorable terms. 2) Buy assets on favorable terms. This book is about the first idea: insure your portfolio when it pays to do so. Happily, the insurance costs the least during bull markets, when everyone is hyperconfident. It costs the most during bear markets, where everyone is hyper-scared. So hedge more when it is cheap, and less when it is expensive. Simple, huh? But the book leaves this idea implicit. It never states it this plainly.

Second, I like his idea that the safest route is the one that maximizes expected wealth over time. That is underappreciated by asset managers.

Third, I appreciate that he brings in the Kelly Criterion, which is one of the best ways to deal with the risk-reward question, which in this case, is how you size your hedges.

Finally, he talks about maximizing the fifth percentile of likely outcomes, which in a well-structured model will keep the investor in the game, allowing the investor to cruise through bear markets, and stay invested. Hey, many actuaries have been doing that for life insurers over the last 25 years. Welcome to the club.

The Central Conundrum

He classifies his hedges as store-of-value, alpha, and insurance. Store of value is short-term savings that has no possibility of loss, which oddly he has at 7%/yr. That might be a long term average, or not, but when modeling the future, variables have to be forward-looking. There is no sign of 7% on the horizon at no risk.

He includes gold in this bucket, and thinks it is a genuine diversifier, with which I agree. Then there is alpha, which for him is commodity trading advisors who are trend followers, who do well when volatility is high. He also briefly touches on a variety of investments that he has tested, and finds they don’t aid the growth of terminal net worth on average.

Then there is insurance, which he never spells out exactly what it is, and the author says it is the most effective way to hedge, and profit. He hides his trade secrets.

What he should have told you I will reveal here. The insurance he is probably talking about is put options on stock or corporate bond indexes (particularly high-yield), or paying for protection on indexed credit-default swaps (best, but only institutions can do this). Imagine paying a constant percentage portfolio value by period to protect your portfolio. When valuations are high, implied volatility is low, and the insurance is cheap when you need it. When valuations are low, implied volatility is high, and the insurance is expensive when you don’t need it. In that situation, your existing hedges might have appreciated so much that you sell them off and go unhedged. Implied volatility can only go so high, before it mean-reverts. When option prices get high, potential hedgers and speculators who would be option buyers sit on their hands, and don’t do anything.

Quibbles

Already stated.

Summary / Who Would Benefit from this Book

If you have read this book review, you have learned more than the book will give you. I really don’t think many people will learn much from this book.

Full disclosure: The publisher kind of pushed a free copy on me, after I commented that I wasn’t crazy about the author’s last book.