Estimating Future Stock Returns

There are many alternative models for attempting to estimate how undervalued or overvalued the stock market is. ?Among them are:

- Price/Book

- P/Retained Earnings

- Q-ratio (Market Capitalization of the entire market /?replacement cost)

- Market Capitalization of the entire market / GDP

- Shiller?s CAPE10 (and all modified versions)

Typically these explain 60-70% of?the variation in stock returns. ?Today I can tell you there is a better model, which is not mine, I found it at the blog?Philosophical Economics.? The basic idea of the model is this: look at the proportion of US wealth held by private investors in stocks using the?Fed?s Z.1 report. The higher the proportion, the lower future returns will be.

There are two aspects of the intuition here, as I see it: the simple one is that when ordinary people are scared and have run from stocks, future returns tend to be higher (buy panic). ?When ordinary people are buying stocks with both hands, it is time to sell stocks to them, or even do IPOs to feed them catchy new overpriced stocks (sell greed).

The second intuitive way to view it is that it is analogous to Modiglani and Miller’s capital structure theory, where assets return the same regardless of how they are financed with equity and debt. ?When equity is a small component as?a percentage of market value, equities will return better than when it is a big component.

What it Means Now

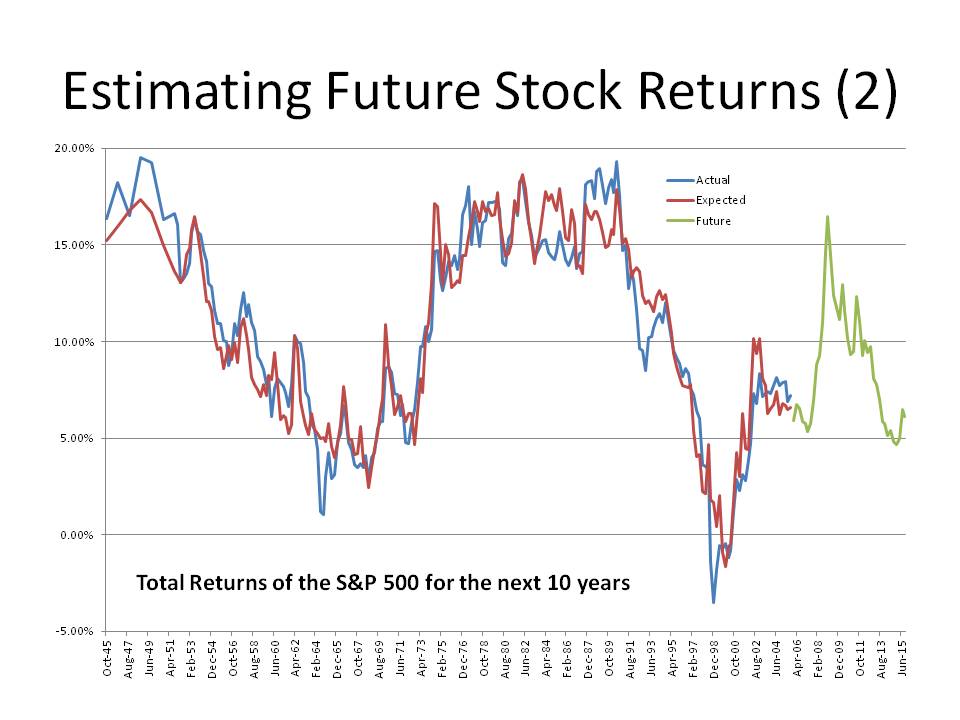

Now, if you look at the graph at the top of my blog, which was estimated back in mid-March off of year-end data, you can notice a few?things:

- The formula explains more than 90% of the variation in return over a ten-year period.

- Back in March of 2009, it estimated returns of 16%/year over the next ten years.

- Back in March of 1999, it estimated returns of -2%/year over the next ten years.

- At present, it forecasts returns of 6%/year, bouncing back from an estimate of around 4.7% one year ago.

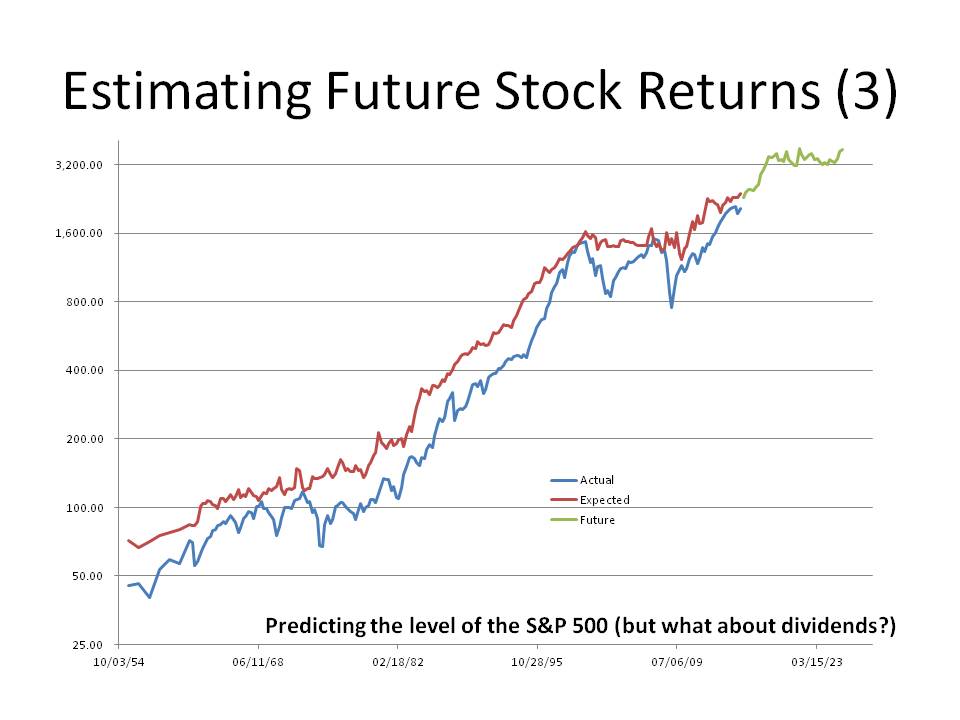

I have two more graphs to show on this. ?The first one below is showing the curve as I tried to fit it to the level of the S&P 500. ?You will note that it fits better at the end. ?The reason for that it is?not a total return index and so the difference going backward in time are the accumulated dividends. ?That said, I can make the statement that the S&P 500 should be near 3000 at the end of 2025, give or take several hundred points. ?You might say, “Wait, the graph looks higher than that.” ?You’re right, but I had to take out the anticipated dividends.

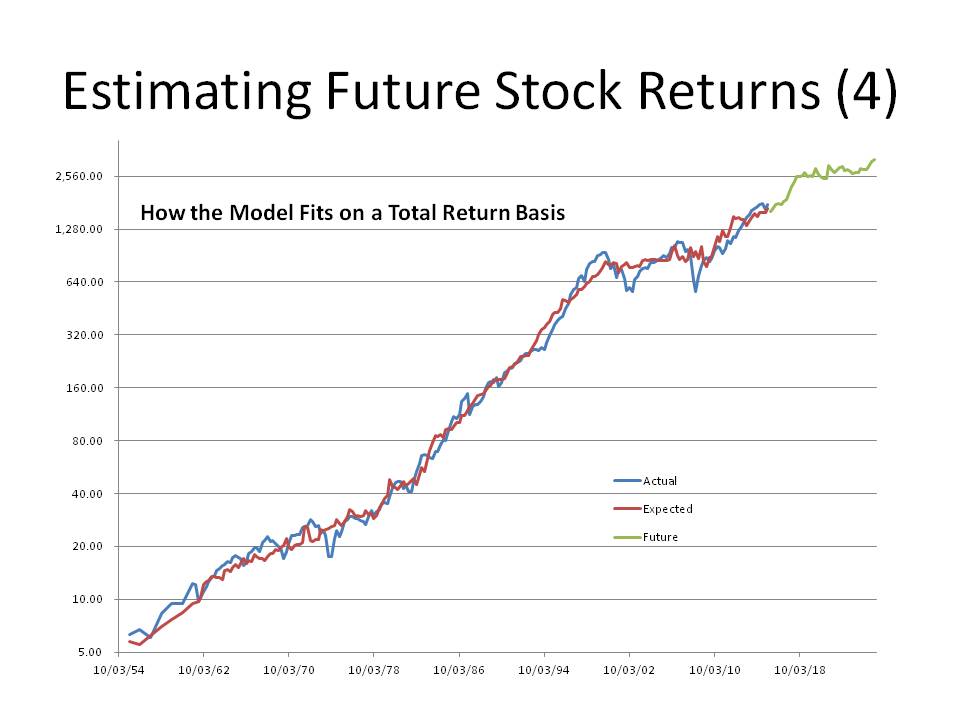

The next graph shows the fit using a homemade total return index. ?Note the close fit.

Implications

If total returns from stocks are only likely to be 6.1%/year (w/ dividends @ 2.2%) for the next 10 years, what does that do to:

- Pension funding / Retirement

- Variable annuities

- Convertible bonds

- Employee Stock Options

- Anything that relies on the returns from stocks?

Defined benefit pension funds are expecting a lot higher returns out of stocks than 6%. ?Expect funding gaps to widen further unless contributions increase. ?Defined contributions face the same problem, at the time that the tail end of the Baby Boom needs returns. ?(Sorry, they *don’t* come when you need them.)

Variable annuities and high-load mutual funds take a big bite out of scant future returns — people will be disappointed with the returns. ?With convertible bonds, many will not go “into the money.” ?They will remain bonds, and not stock substitutes. ?Many employee stock options and stock ownership plan will deliver meager value unless the company is hot stuff.

The entire capital structure is consistent with low-ish?corporate bond yields, and low-ish volatility. ?It’s a low-yielding environment for capital almost everywhere. ?This is partially due to the machinations of the world’s central banks, which have tried to stimulate the economy by lowering rates, rather than letting recessions clear away low-yielding projects that are unworthy of the capital that they employ.

Reset Your Expectations and Save More

If you want more at retirement, you will have to set more aside. ?You could take a chance, and wait to see if the market will sell off, but valuations today are near the 70th percentile. ?That’s high, but not nosebleed high. ?If this measure got to levels 3%/year returns, I would hedge my positions, but that would imply the S&P 500 at around?2500. ?As for now, I continue my ordinary investing posture. ?If you want, you can do the same.

=–==-=-=-=-=-=–=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==–=

PS — for those that like to hear about little things going on around the Aleph Blog, I would point you to this fine website that has started to publish some of my articles in Chinese. ?This article?is particularly amusing to me with my cartoon character illustrating points. ?This is the English article that was translated. ?Fun!