Bumped Against My Upper Cash Limit

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

In the time I have been managing money for myself and others in my stock strategy, I set a limit on the amount of cash in the strategy. ?I don’t let it go below 0%, and I don’t let it go over 20%.

I have bumped against the lower limit six or so?times in the last sixteen years. ?I bumped against it around five times in 2002, and once in 2008-9. ?All occurred near the bottom of the stock market. ?In 2002, I raised cash by selling off the stocks that had gotten hurt the least, and concentrating in sound stocks that had taken more punishment. ?In September 2002, when things were at their worst, I scraped together what spare cash I had, and invested it. ?I don’t often do that.

In 2008-9 I behaved similarly, though my household cash situation was tighter. ?Along with other stocks I thought were bulletproof, but had gotten killed, I bought a double position of RGA near the bottom, and then held it until last week, when it finally broke $100.

But, I had never run into a situation yet where I bumped into the 20% cash limit until yesterday. ?Enough of my stocks ran up such that I have been selling small bits of a number of companies for risk control purposes. ?The cash started to build up, and I didn’t have anything that I deeply wanted to own, so it kept building. ?As the limit got closer, I had one stock that I liked that would serve as at least a temporary place to invest — Tesoro [TSO]. ?Seems cheap, reasonably financed, and refining spreads are relatively low right now. ?I bought a position in Tesoro yesterday.

I could have done other things. ?I could have moved the position sizes of my portfolio up, but I would have had to increase the position sizes a lot to have some stocks hit the lower edge of the trading band,?but that would have been more bullish than I feel now. ?As it is, refiners have been lagging — I can live with more exposure there to augment Valero, Marathon Petroleum and PBF.

I also could have doubled a position size of an existing holding, but I didn’t have anything that I was that?impressed with. ?It takes a lot to make me double a position size.

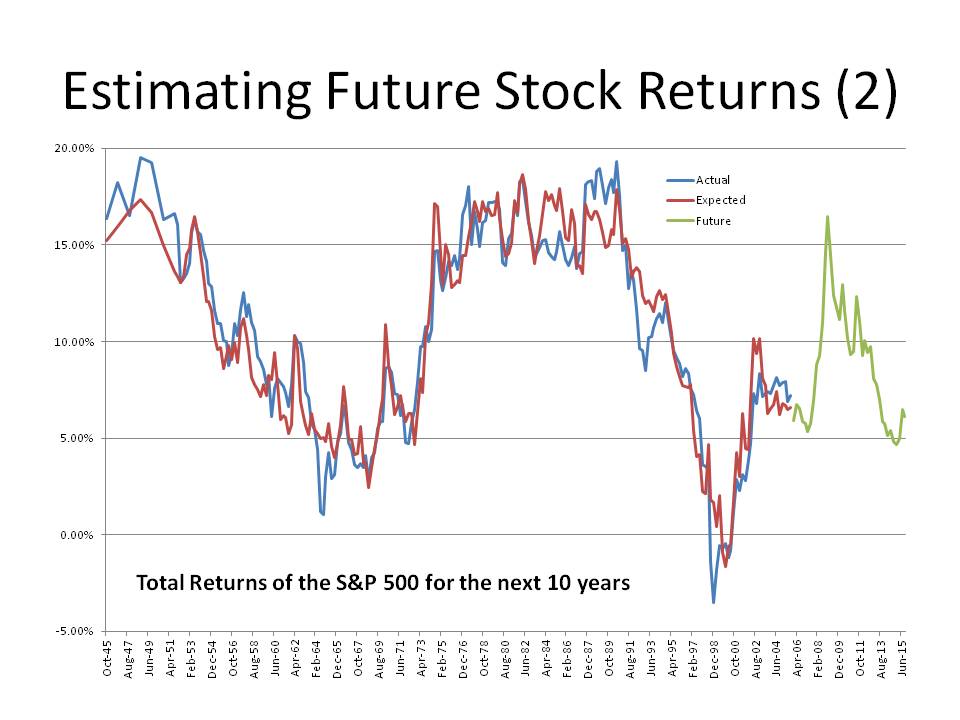

As it is, my actions are that of following the rules that discipline my investing, but acting in such a way that reflects my moderate bearishness over the intermediate term. ?In the short run, things can go higher; the current odds even favor that, though at the end the market plays for small possible gains versus a larger possible loss.

The credit cycle is getting long in the tooth; though many criticize the rating agencies, their research (not their ratings) can serve as a relatively neutral guidepost to investors. ?Corporate debt is high and increasing, and profits are flat to shrinking… not the best setup for longs. ?(Read John Lonski at Moody’s.)

I will close this piece by saying that I am looking over my existing holdings and analyzing them for need for financing over the next three years, and selling those that seem weak… though what I will replace them with is a mystery to me.

Bumping up against my upper cash limit is bearish… and that is what I am working through now.

Full disclosure: long VLO MPC PBF and TSO