==========================================

I will admit, when I first read about the Permanent Portfolio in the late-80s, I was somewhat skeptical, but not totally dismissive.? Here is the classic Permanent Portfolio, equal proportions of:

- S&P 500 stocks

- The longest Treasury Bonds

- Spot Gold

- Money market funds

Think about Inflation, how do these assets do?

- S&P 500 stocks ? mediocre to pretty good

- The longest Treasury Bonds ? craters

- Spot Gold ? soars

- Money market funds ? keeps value, earns income

Think about Deflation, how do these assets do?

- S&P 500 stocks ? pretty poor to pretty good

- The longest Treasury Bonds ? soars

- Spot Gold ? craters

- Money market funds ? makes a modest amount, loses nothing

Long bonds and gold are volatile, but they are definitely negatively correlated in the long run.? The Permanent Portfolio concept attempts to balance the effects of inflation and deflation, and capture returns from the overshooting that these four asset classes do.

What did I do?

I got the returns data from 12/31/69 to 9/30/2011 on gold, T-bonds, T-bills, and stocks.? I created a hypothetical portfolio that started with 25% in each, rebalancing to 25% in each whenever an asset got to be more than 27.5% or less than 22.5% of the portfolio.? This was the only rebalancing strategy that I tested.? I did not do multiple tests and pick the best one, because that would induce more hindsight bias, where I torture the data to make it confess what I want.

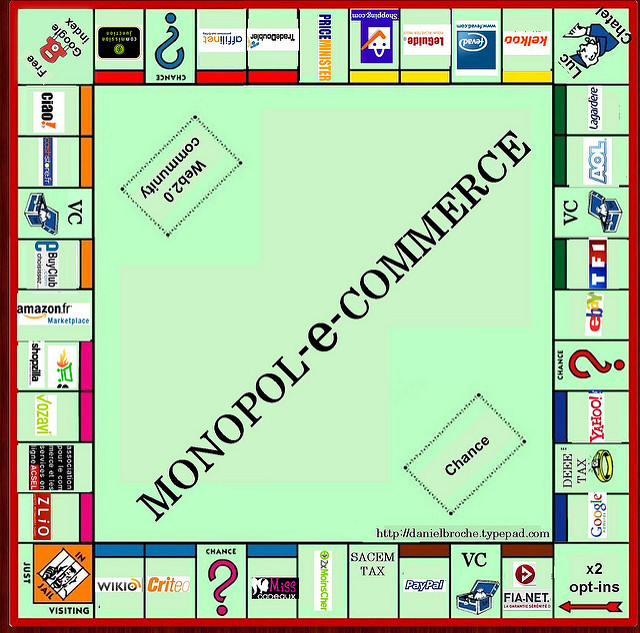

I used a 10% band around 25% ( 22.5%-27.5%) figuring that it would rebalance the portfolio with moderate frequency.? Over the 566 months of the study, it rebalanced 102?times. ?At the top of this article is a graphical summary of the results.

The smooth-ish gold line in the middle is the Permanent Portfolio.? Frankly, I was surprised at how well it did.? It did so well, that I decided to ask, what if we drop out the T-bills in order to leverage the idea.? It improves the returns by 1%, but kicks up the 12-month drawdown by 7%.? Probably not a good tradeoff, but pretty amazing that it beats stocks with lower than bond drawdowns. ?That’s the light brown line.

| Results |

S&P TR |

Bond TR |

T-bill TR |

Gold TR |

PP TR |

PP TR levered |

| Annualized Return |

10.40% |

8.38% |

4.77% |

7.82% |

8.80% |

9.93% |

| Max 12-mo drawdown |

-43.32% |

-22.66% |

0.02% |

-35.07% |

-7.65% |

-14.75% |

Now the above calculations assume no fees.? If you decide to implement it using SPY, TLT, SHY and GLD, (or something similar) there will be some modest level of fees, and commission costs.

?What Could Go Wrong

Now, what could go wrong with an analysis like this?? The first point is that the history could be unusual, and not be indicative of the future.? What was unusual about the period 1970-2017?

- Went off the gold standard; individual holding of gold legalized.

- High level of gold appreciation was historically abnormal.

- Deregulation of money markets allowed greater volatility in short-term rates.

- ZIRP crushed money market rates.

- Federal Reserve micro-management of short-term rates led to undue certainty in the markets over the efficacy of monetary policy ? ?The Great Moderation.?

- Volcker era interest rates were abnormal, but necessary to squeeze out inflation.

- Low long Treasury rates today are abnormal, partially due to fear, and abnormal Fed policy.

- Thus it would be unusual to see a lot more performance out of long Treasuries. The stellar returns of the past can?t be repeated.

- Three hard falls in the stock market 1973-4, 2000-2, 2007-9, each with a comeback.

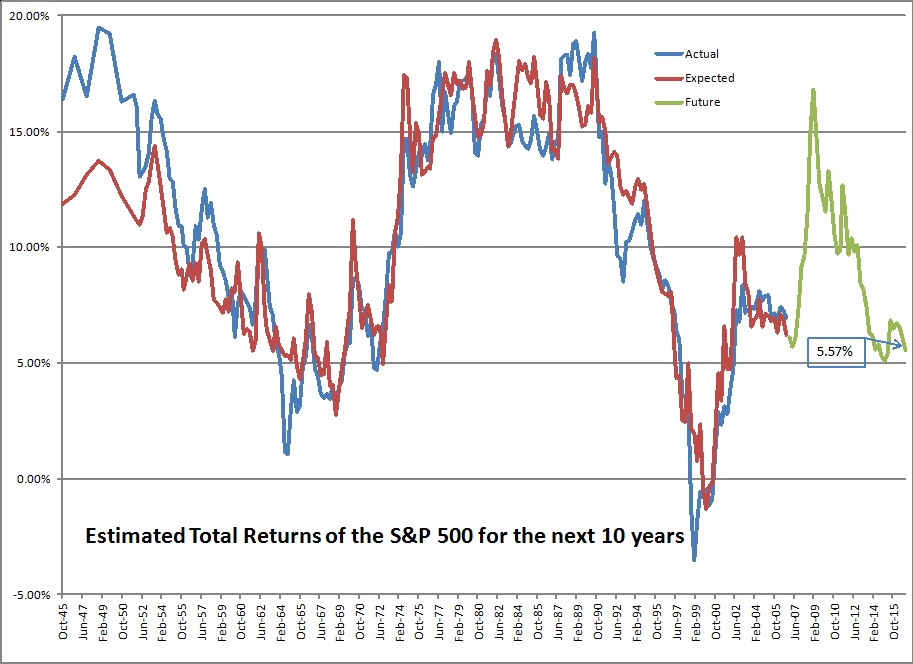

- By the end of the period, profit margins for stocks were abnormally high, and overvaluations are significant.

But maybe the way to view the abnormalities of the period as being ?tests? of the strategy.? If it can survive this many tests, perhaps it can survive the unknown tests of the future.

Other risks, however unlikely, include:

- Holding gold could be made illegal again.

- The T-bills and T-bonds have only one creditor, the US Government. Are there scenarios where they might default for political reasons?? I think in most scenarios bondholders get paid, but who can tell?

- Stock markets can close for protracted periods of time; in principle, public corporations could be made illegal, as they are statutory creations.

- The US as a society could become less creative & productive, leading to malaise in its markets. Think of how promising Argentina was 100 years ago.

But if risks this severe happen, almost no investment strategy will be any good.? If the US isn?t a desirable place to live, what other area of the world would be?? And how difficult would it be to transfer assets there?

Summary

The Permanent Portfolio strategy is about as promising as any that I have seen for preserving the value of assets through a wide number of macroeconomic scenarios.? The volatility is low enough that almost anyone could maintain it.? Finally, it?s pretty simple.? Makes me want to consider what sort of product could be made out of this.

=======================================================

Back to the Present

I delayed on posting this for a while — the original work was done five years ago. ?In that time, there has been a decent amount of digital ink spilled on the Permanent Portfolio idea of Harry Browne’s. ?I have two pieces written:?Permanent Asset Allocation, and?Can the ?Permanent Portfolio? Work Today?

Part of the recent doubt on the concept has come from three sources:

- Zero Interest rate policy [ZIRP] since late 2008, (6.8%/yr PP return)

- The fall in Gold since late 2012 (2.7%/yr PP return), and

- The fall in T-bonds in since mid-2016 (-4.7%?annualized PP return).

Out of 46 calendar years, the strategy makes money in 41 of them, and loses money in 5 with the losses being small: 1.0% (2008), 1.9% (1994), 2.2% (2013), 3.6% (2015), and 4.5% (1981). ?I don’t know about what other people think, but there might be a market for a strategy that loses ~2.6% 11% of the time, and makes 9%+?89% of the time.

Here’s the thing, though — just because it succeeded in the past does not mean it will in the future. ?There is a decent theory behind the Permanent Portfolio, but can it survive highly priced bonds and stocks? ?My guess is yes.

Scenarios: 1) inflation runs, and the Fed falls behind the curve — cash and gold do well, bonds tank, and stocks muddle. ?2) Growth stalls, and so does the Fed: bonds rally, cash and stocks muddle, and gold follows the course of inflation. 3) Growth runs, and the Fed swarms with hawks. Cash does well, and the rest muddle.

It’s hard, almost impossible to make them all do badly at the same time. ?They react differently to?changes in the macro-economy.

Upshot

There are a lot of modified permanent portfolio ideas out there, most of which have done worse than the pure strategy. ?This permanent portfolio strategy?would be relatively pure. ?I’m toying with the idea of a lower minimum ($25,000) separate account that would hold four funds and rebalance as stated above, with fees of 0.2% over the ETF fees. ?To minimize taxes, high cost tax lots would be sold first. ?My question is would there be interest for something like this? ?I would be using a better set of ETFs than the ones that I listed above.

I write this, knowing that I was disappointed when I started out with my equity management. ?Many indicated interest; few carried through. ?Small accounts and a low fee structure do not add up to a scalable model unless two things happen: 1) enough accounts want it, and 2) all reporting services are provided by Interactive Brokers.

Closing

Besides, anyone could do the rebalancing strategy. ?It’s not rocket science. ?There are enough decent ETFs to use. ?Would anyone truly want to pay 0.2%/yr on assets to have someone select the funds and do the rebalancing for him? ?I wouldn’t.