Who Needs Liquidity Most?

-==-=-=-

Here’s the quick summary of what I will say: People and companies need liquidity. ?Anything where payments need to be made needs liquidity. ?Secondary markets will develop their own liquidity if it is needed.

Recently, I was at an annual meeting of a private company that I own shares in. ?Toward the end of the meeting, one fellow who was kind of new to the firm asked?what liquidity the shares had and how people valued them. ?The board and management of the company wisely said little. ?I gave a brief extemporaneous talk that said that most people who owned these shares know they are illiquid, and as such, they hold onto them, and enjoy the distributions. ?I digressed a little and explained how one *might* put a value on the shares, but trading values really depended on who was more motivated — the buyer or the seller.

Now, there’s no need for that company to have a liquid market in its stock. ?In general, if someone wants to sell, someone will buy — trades are very infrequent, say a handful per year. ?But the holders know that, and most plan not to sell the shares, looking to other sources if they need money to spend — liquidity.

And in one sense, the shares generate their own flow of liquidity. ?The distributions come quite regularly. ?Which would you rather have? ?A bucket of golden eggs, or the goose that lays them one at a time?

Now the company itself doesn’t need liquidity. ?It generates its liquidity internally through profitable operations that don’t require much in the way of reinvestment in order to maintain its productive capacity.

Now, Buffett used to?purchase only companies that were like this, because he wanted to reallocate the excess liquidity that the companies threw off to new investments. ?But as time has gone along, he has purchased capital-intensive businesses like BNSF that require continued capital investment. ?Quoting from a good post at Alpha Architect?referencing Buffett’s recent annual meeting:

Question: ?In your 1987 Letter to Shareholders, you commented on the kind of companies Berkshire would like to buy: those that required only small amounts of capital. You said, quote, ?Because so little capital is required to run these businesses, they can grow while concurrently making all their earnings available for deployment in new opportunities.? Today the company has changed its strategy. It now invests in companies that need tons of capital expenditures, are over-regulated, and earn lower returns on equity capital. Why did this happen?

Warren Buffett?It?s one of the problems of prosperity. The ideal business is one that takes no capital, but yet grows, and there are a few businesses like that. And we own some?We?d love to find one that we can buy for $10 or $20 or $30 billion that was not capital intensive, and we may, but it?s harder. And that does hurt us, in terms of compounding earnings growth. Because obviously if you have a business that grows, and gives you a lot of money every year?[that] isn?t required in its growth, you get a double-barreled effect from the earnings growth that occurs internally without the use of capital and then you get the capital it produces to go and buy other businesses?[our] increasing capital [base] acts as an anchor on returns in many ways. And one of the ways is that it drives us into, just in terms of availability?into businesses that are much more capital intensive.

Emphasis that of Alpha Architect

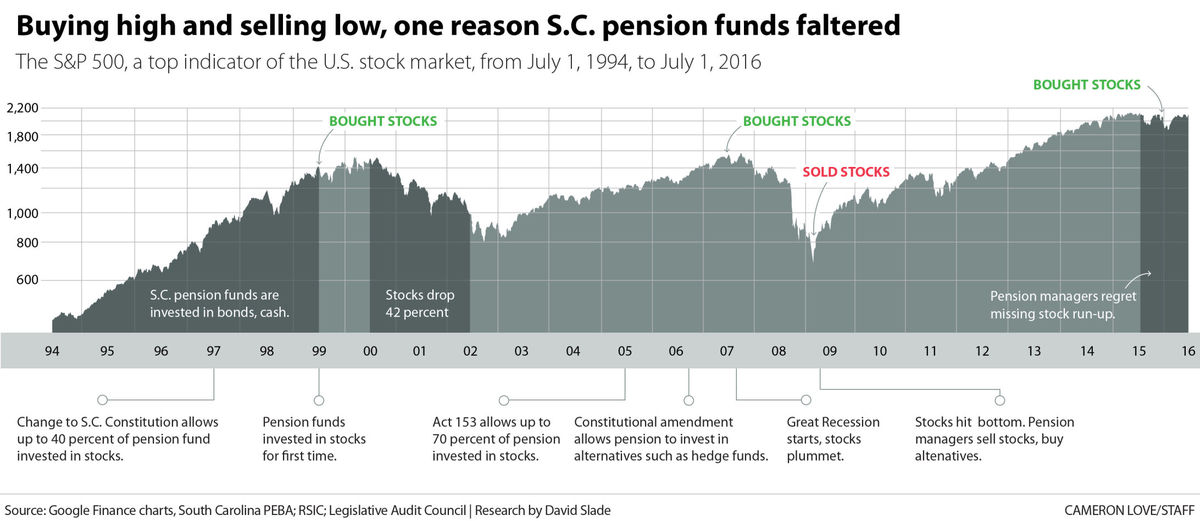

Liquidity is meant to support the spending of corporations and people who need services and products to further their existence. ?As such, intelligent entities plan for liquidity needs in advance. ?A pension plan in decline allocates more to bonds so that the cash flow from the bonds will fund expected net payouts. ?Well-run insurance companies and banks match expected cash flows at least for a few years.

Buffer funds are typically low-yielding assets of high quality and short duration — short maturity bonds, CDs, savings and bank deposits, etc. ?Ordinary people and corporations need them to manage the economic bumps of life. ?Expenses are up, and current income doesn’t exceed them. ?Got cash? ?It certainly helps to be able to draw on excess assets in a pinch. ?Those who run a balance on their credit cards pay handsomely for the convenience.

In a crisis, who needs liquidity most? ?Usually, it’s whoever is at the center of the crisis, but usually, those entities are too far gone to be helped. ?More often, the helpable needy are the lenders to those at the center of the crisis, and woe betide us if no one will privately lend to them. ?In that case, the financial system itself is in crisis, and then people end up lending to whoever is the lender of last resort. ?In the last crisis, Treasury bonds rallied as a safe haven.

In that sense, liquidity is a ‘fraidy cat. ?Marginal borrowers can’t get it when they need it most. ?Liquidity typically flows to quality in a crisis. ?Buffett bailed out only the highest quality companies in the last crisis. Not knowing how bad it would be, he was happy to hit singles, rather than risk it on home runs.

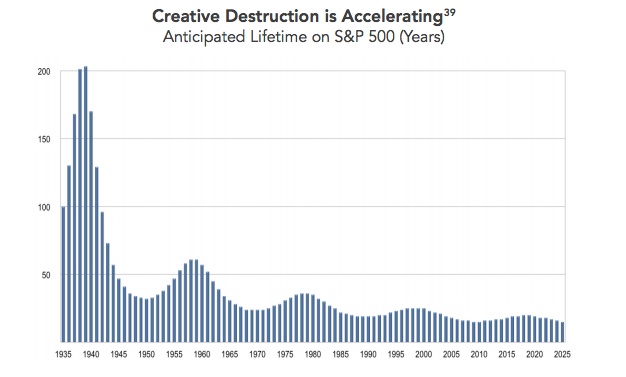

Who needs liquidity most now? ?Hard to say. ?At present in the US, liquidity is plentiful, and almost any?person or firm can get a loan or equity finance if they want it. ?Companies happily extend their balance sheets, buying back stock, paying dividends, and occasionally investing. ?Often when liquidity is flush, the marginal bidder is a speculative entity. ?As an example, perhaps some emerging market countries, companies and people would like additional offers of liquidity.

That’s a major difference between bull and bear markets — the quality of those that can easily get unsecured loans. ?To me that is the leading reason why we are in the seventh or eighth inning of a bull market now, because almost any entity can get the loans they want at attractive levels. ?Why isn’t it the ninth inning? ?We’re not at “nuts” levels yet. ?We may never get there though, which is why baseball analogies are sometimes lame. ?Some event can disrupt the market when it is so high, and suddenly people and firms are no longer so willing to extend credit.

Ending the article here — be aware. ?The time to take inventory of your assets and their financing needs is before the markets have an event. ?I’ve just completed my review of my portfolio. ?I sold two of the 35 companies that I hold and replaced them with more solid entities that still have good prospects. ?I will sell two more in the new year for tax reasons. ?My bond portfolio is high quality. ?My clients and I are ready if liquidity gets worse.

Are you ready?